JBC: Antibiotic resistance in pandemic cholera

Cholera is a devastating disease for millions worldwide, primarily in developing countries, and the dominant type of cholera today is naturally resistant to one type of antibiotic usually used as a treatment of last resort.

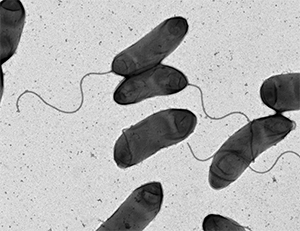

This image shows an electron micrograph of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera. courtesy of M. Stephen Trent/University of Georgia

This image shows an electron micrograph of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera. courtesy of M. Stephen Trent/University of Georgia

Researchers at the University of Georgia now have shown that the enzyme that makes the El Tor family of Vibrio cholera resistant to those antibiotics has a different mechanism of action from any comparable proteins observed in bacteria so far. Understanding that mechanism better equips researchers to overcome the challenge it presents in a world with increasing antibiotic resistance. The research was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Cationic antimicrobial peptides, or CAMPs, are produced naturally by bacteria and by animals’ innate immune systems and also are synthesized for use as last-line drugs. Cholera strains achieve resistance to CAMPs by chemically disguising the bacterium’s cell wall, which prevents CAMPs from binding, disrupting the wall and killing the bacterium. M. Stephen Trent’s research team in Georgia previously had shown that a group of three proteins carried out this modification and had elucidated the functions of two of the proteins. The team reported the role of the third protein — the missing piece in understanding CAMP resistance — in the new paper.

Jeremy Henderson, then a graduate student, led a research project that showed that this enzyme, AlmG, attaches glycine, the smallest of the amino acids, to lipid A, one of the components of the outer membrane of the bacterial cell. This modification changes the charge of the lipid A molecules, preventing CAMPs from binding.

Lipid A modification is a defense mechanism observed in other bacteria, but detailed biochemical characterization of AlmG showed that the way this process occurred in cholera was unique.

“It became apparent over the course of our work that how (this enzyme) improves shield functionality is quite different than would be expected based on what we know about groups of enzymes that look similar,” Henderson said.

AlmG is structured differently from other lipid A-modifying enzymes, with a different active site responsible for carrying out the modification. In addition, AlmG can add either one or two glycines to the same lipid A molecule, which also has not been observed in other bacteria. “It just opens up the door for this operating with a completely different mechanism than what’s been described in the literature for related proteins,” Henderson said.

Genes encoding determinants of antibiotic resistance can spread between different species of bacteria, so the unique mechanism of CAMP drug resistance in V. cholerae is of potential concern if it jumps to bacteria already resistant to first-line drugs. “The level of protection conferred by this particular modification in Vibrio cholerae puts it in a league of its own,” Henderson said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)