JBC: A rare blood disease can teach us about clotting

When a person is injured, blood clotting is essential. However, once the danger has passed, it is equally essential to stop the clotting response in order to prevent thrombosis, or the obstruction of blood flow by clots. A protein called antithrombin is responsible for stopping coagulation, but about one in 2,000 people have a hereditary deficiency in antithrombin that puts them at much higher risk of life-threatening blood clots.

Researchers in Spain have analyzed the mutations in the antithrombin proteins of these patients and discovered that a section of the protein plays an unexpected role in its function. This insight into how antithrombin works could lead not only to treatments for patients with antithrombin deficiency, but also to better-designed drugs for other blood disorders. The research was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

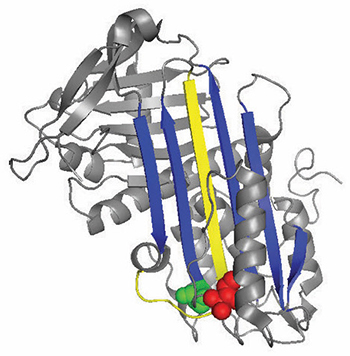

A ribbon diagram of antithrombin highlights locations of functionally important mutations.

Courtesy of Irene Martínez–Martínez/Universidad de Murcia

A ribbon diagram of antithrombin highlights locations of functionally important mutations.

Courtesy of Irene Martínez–Martínez/Universidad de Murcia

The Centro Regional de Hemodonacion and Hospital Universitario Morales Meseguer of the Universidad de Murcia in Spain is a reference center for the diagnosis of antithrombin deficiency. For more than 15 years, researchers at the laboratory have been receiving samples from patients with diverse mutations that affect how their antithrombin works.

Antithrombin normally inhibits thrombin by inserting a loop-shaped region, called the reactive center loop, into the active site of the thrombin protein, preventing thrombin from catalyzing clot formation by distorting the shape of the thrombin’s active site. Many antithrombin mutations that cause clotting diseases directly or indirectly affect the reactive center loop. However, biochemical studies led by Irene Martinez–Martinez discovered that mutations in a completely different part of the antithrombin also contributed to its dysfunction.

“We saw that we (had) mutants that were affecting the function of the protein even though they were very far from the main part of the protein that is in charge of the inhibition,” Martínez–Martínez said. “People thought that the antithrombin function was mainly focused on one domain of the protein. With this work, we have realized that is not true.”

The researchers’ analyses of the new mutations suggested that the domain of the antithrombin at the opposite end of the reactive center loop helps keep the thrombin trapped in its final, distorted form. When there were specific mutations in this region, the thrombin was more often able to return to its active form and degrade and release the antithrombin.

Martínez–Martínez hopes that understanding the importance of this region of the antithrombin could lead to better drugs for preventing blood clotting by activating antithrombin or preventing bleeding by inhibiting it. She also emphasizes that the essential nature of this domain of the protein could not have been predicted from simply studying the sequences of healthy antithrombins.

“This work has been possible thanks to the characterization of mutations identified in patients,” Martínez–Martínez said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

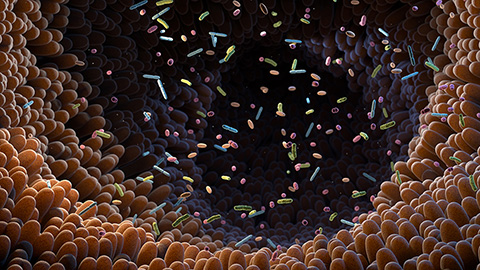

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

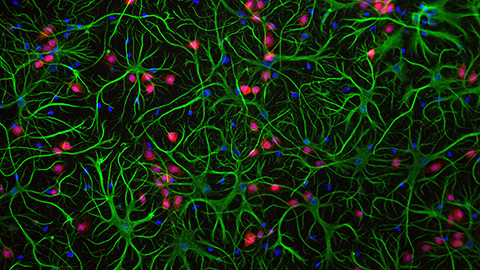

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)