JBC: A molecular dance of phospholipid synthesis

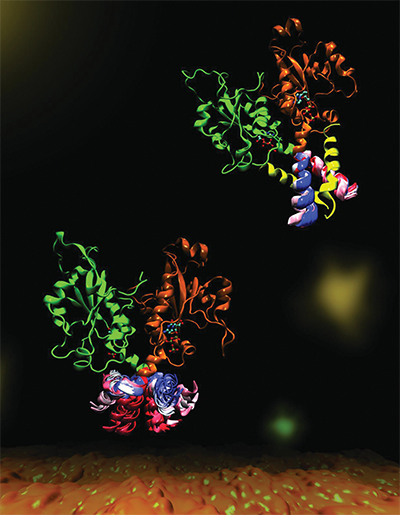

CCT is a key enzyme that maintains a balanced composition of cell membrane phospholipids. This image highlights the dynamics of a portion of the enzyme CCT that is essential for regulation of its functions. Mohsen Ramezanpour and Jaeyong Lee

CCT is a key enzyme that maintains a balanced composition of cell membrane phospholipids. This image highlights the dynamics of a portion of the enzyme CCT that is essential for regulation of its functions. Mohsen Ramezanpour and Jaeyong Lee

The most abundant molecule in cell membranes is the lipid phosphatidylcholine, or PC, commonly known as lecithin; accordingly, the enzymes responsible for synthesizing it are essential. Research published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry used computer simulations to gain insights into how one of these enzymes activates and shuts off PC production. The results could help researchers understand why small changes in this enzyme can lead to conditions like blindness and dwarfism.

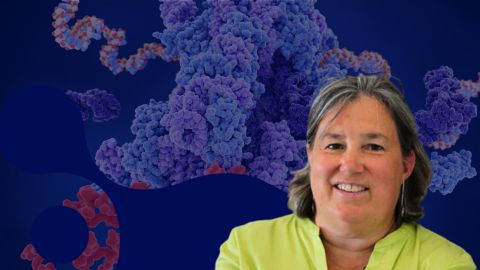

Rosemary Cornell, a professor of molecular biology and biochemistry at Simon Fraser University in Canada, studies the enzyme CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase, or CCT. CCT sets the rate of PC production in cells by binding to cell membranes with low PC content. When bound to membranes, the CCT enzyme changes shape in a way that allows it to carry out the key rate-limiting step in PC synthesis. When the amount of PC making up the membrane increases, the CCT falls off the membrane, and PC production ceases.

“The membrane is this big macromolecular array with lots of different molecules in it,” Cornell said. “How does this enzyme recognize that ‘Oh, I should slow down because the PC content of the membrane is getting too high?’”

Cornell and her project team — a collaboration with Peter Tieleman and graduate student Mohsen Ramezanpour at the University of Calgary and Jaeyong Lee and Svetla Taneva, research associates at SFU — thought the answer must have to do with the enzyme’s dynamic changes in shape when it binds to a membrane. But these changes are difficult to capture with traditional structural biology methods such as X-ray crystallography, which take a static snapshot of molecules. Instead, the team used computational simulations of molecular dynamics, which use information about the forces between every individual atom in a molecule to calculate the trajectories of the enzyme’s moving parts.

“What it looks like (when you visualize the output) is your big molecule dancing in front of your eyes,” Cornell said. “We set up the molecular dynamics simulation not once, not twice, but 40 different (times). It took months and months just to do the computational parts and even more months trying to analyze the data afterward. We actually spent a lot of time once we got the data just looking on the screen at these dancing molecules.”

The simulated dance of the CCT molecule showed that when the M-domain, the section of the enzyme that typically binds to the membrane, detaches from a membrane, it snags the active site of the enzyme, preventing it from carrying out its reaction. When the snagging segment was removed from the simulation, the team saw a dramatic bending motion in the docking site for the snagging element and speculated that this bending would create a better enzyme active site for catalyzing the reaction when attached to a membrane. They confirmed these mechanisms with biochemical laboratory experiments.

Previous genetic studies had shown that mutations in the gene encoding CCT are responsible for rare conditions like spondylometaphyseal dysplasia with cone-rod dystrophy, which causes severe impairments in bone growth and vision, but it was not known how these changes in the enzyme could lead to such dramatic consequences. Cornell hopes that understanding how the enzyme works could help researchers find the causes of these conditions.

“If you have just one small change in CCT, then how is that going to make this whole process of synthesizing PC defective?” she asked. “That’s what we’re studying right now.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.

Melissa Moore to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)