Genetic research in the midst of a pandemic

Researchers have long believed that our genetic makeup plays an important role in differential disease susceptibility and outcome. Over the last 16 months, clinicians have observed that the severity of COVID-19 varies greatly among different people: Some are asymptomatic or develop only mild symptoms, while others can end up in an intensive care unit and even die.

Andrew Bretherick is a clinical academic track lecturer at Edinburgh University who studies the role of genetics in disease. “Host genetics are known to have a significant impact on disease outcome.” Bretherick said, “which made it hugely important to study the genetic basis of COVID-19 severity.”

In 2020, a team of researchers from the Genetics of Mortality in Critical Care, or GenOMICC, study — an open, collaborative, global community of doctors and scientists studying the genetic factors that affect outcomes in critical illness — analyzed the DNA of 2,244 COVID-19 patients in intensive care units across the U.K. The study was led by Kenneth Baillie, chief investigator and academic consultant in critical care medicine and senior research fellow at University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute. Among the researchers on the project were Bretherick and Sara Clohisey, a core scientist in the Baillie lab.

“At the start of the pandemic, it was important to use our resources to obtain genetic information from COVID-19 patients,” Clohisey said. “Remember, during this time there was little known about SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) itself.”

The nature of GenOMICC’s work (determining the specific genes that control the processes that lead to life-threatening illness, including sepsis and influenza A), made setting up this study much easier and quicker than it otherwise might have been.

“Our standing protocol with GenOMICC allows us to also carry out genetic testing for emerging viruses in critical illness, a category that SARS-CoV-2 fell under,” Clohisey said. “We were pretty well set up to begin this study by March (2020).”

To get a large sample, the group worked with over 200 intensive care units across the U.K. Clohisey highlighted the importance of the work done by the administrative teams at GenOMICC, and the participating hospitals, and praised them for working “tirelessly around the clock for weeks” to ensure that all essential paperwork was completed as efficiently as possible.

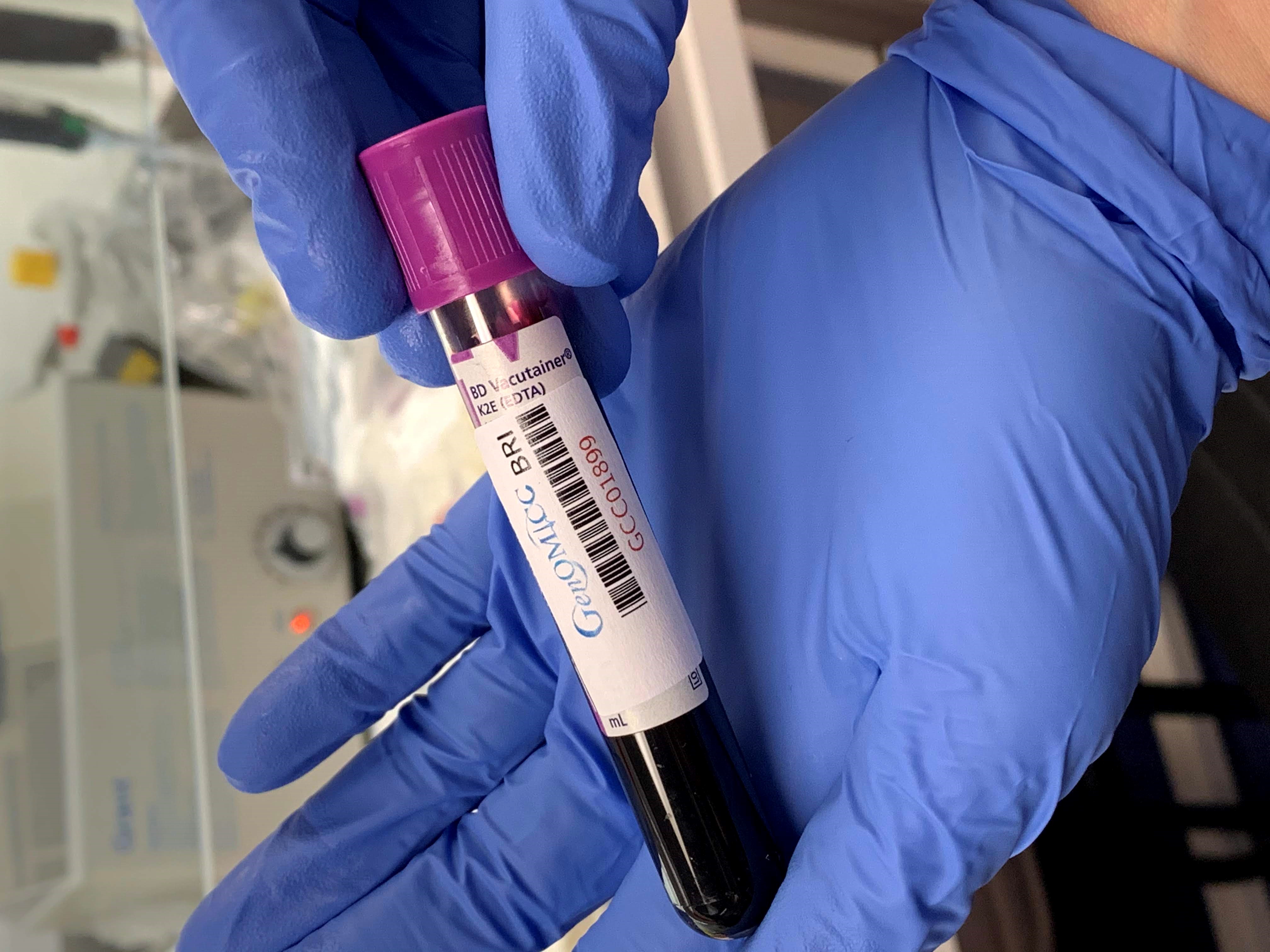

Nurses and doctors collected blood samples from patients with severe COVID-19 who agreed to participate. But before the samples could get to the processing team in Edinburgh, some logistical roadblocks had to be surmounted: Transportation and postal services were delayed across the U.K. due to pandemic lockdown restrictions.

“We actually needed people to build the boxes (required to ship the samples in),” Clohisey said. “We put out a call in at Easter Bush campus (of the University of Edinburgh), and 70 volunteers came to build boxes for us. This was amazing because it showed how invested everyone was in helping out.”

A team at the university’s Edinburgh Clinical Research Facility carried out DNA extractions, quality control and the sequencing from all the delivered samples.

“Once the samples were received, the turnaround was extremely quick,” Bretherick said. “Everybody worked extremely hard, and we had the raw data ready for analysis in a matter of weeks.”

The group performed a genome-wide association study or GWAS (an approach used to identify associations between specific genetic variants and particular diseases) on the processed samples and then compared genotypes in the severe COVID-19 cases with available genetic profiles from uninfected people enrolled in the UK Biobank, Generation Scotland, and 100,000 Genomes projects. The group shared their preliminary results in a preprint published in September and carried out more in-depth analysis for a Nature paper published three months later.

The preprint’s purpose was “to get the results out there to the community and keep research moving forward as quickly as possible,” Bretherick said.

The GWAS results identified several robust genetic signals relating to key host antiviral defense mechanisms and mediators of inflammatory organ damage in severe COVID-19. More specifically, four new genetic loci (potentially associated with the genes TYK2, OAS1/OAS2/OAS3, DPP9 and IFNAR2) were found to be associated with critical COVID-19 illness.

“One of the gene targets of immediate clinical interest was TYK2,” Bretherick said.

The findings suggested that inhibiting TYK2 might prevent people from getting severe COVID-19. Baricitinib belongs to a class of drugs called Janus kinase inhibitors, one of the targets of which is TYK2. Baricitinib already has FDA approval for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Therefore, if found effective, baricitinib could be repurposed to treat COVID-19 with relative ease.

Bretherick believes drug repurposing is a good strategy to identify treatments for COVID-19 as it does not require developing new molecules that might not be approved for clinical use for many years.

“The study highlights the usefulness of using repurposed drugs to treat COVID-19,” Bretherick said, “and helping to choose the right candidates for clinical studies might help save thousands of lives.”

Since the paper’s publication, responses from scientists, patients and the public have been overwhelmingly positive, spurring continued expansion of the study.

The researchers are now collecting more samples, particularly from patients who have tested positive with mild COVID-19 symptoms (no hospitalization). With blood collection drives set up across the U.K., over 5,000 samples have been collected so far. Clohisey and Bretherick anticipate getting many more.

“As the sample size grows, we'll be able to pick up smaller and subtler genetic effects,” Bretherick said, “However, although the genetic effects may be small, the impact on clinical outcome may be large. Exactly what the impact will be remains to be seen.”

COVID-19 has affected communities across the globe, and the group hopes to capture as much ethnic diversity in their upcoming studies as possible.

Clohisey and Bretherick are part of a large collaborative team. The Nature paper cites 72 individuals and groups as authors, and many administrators and volunteers have also contributed as detailed in the extended contributor list.

“If we do the math, there are thousands of people who have helped make this genetic study successful,” Clohisey said. “It really shows the amazing work that can be accomplished when people work together toward a common goal.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

CRISPR epigenome editor offers potential neurodevelopmental gene therapies

Scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, created a system to modify the methylation patterns in neurons. They presented their findings at ASBMB 2025.

Finding a symphony among complex molecules

MOSAIC scholar Stanna Dorn uses total synthesis to recreate rare bacterial natural products with potential therapeutic applications.

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.