Not so selfish after all: Viruses use freeloading genes as weapons

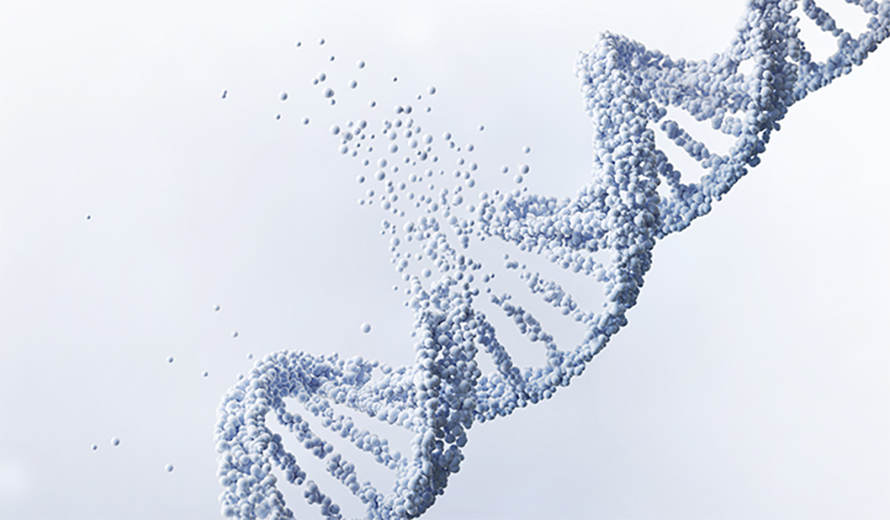

Curious bits of DNA tucked inside genomes across all kingdoms of life historically have been disregarded since they don’t seem to have a role to play in the competition for survival. Or so researchers thought.

These DNA pieces came to be known as “selfish genetic elements” because they exist, as far as scientists could tell, to simply reproduce and propagate themselves, without any benefit to their host organisms. They were seen as genetic hitchhikers that have been inconsequentially passed from one generation to the next.

Research conducted by scientists at the University of California San Diego has provided fresh evidence that such DNA elements might not be so selfish after all. Instead, they now appear to factor considerably into the dynamics between competing organisms.

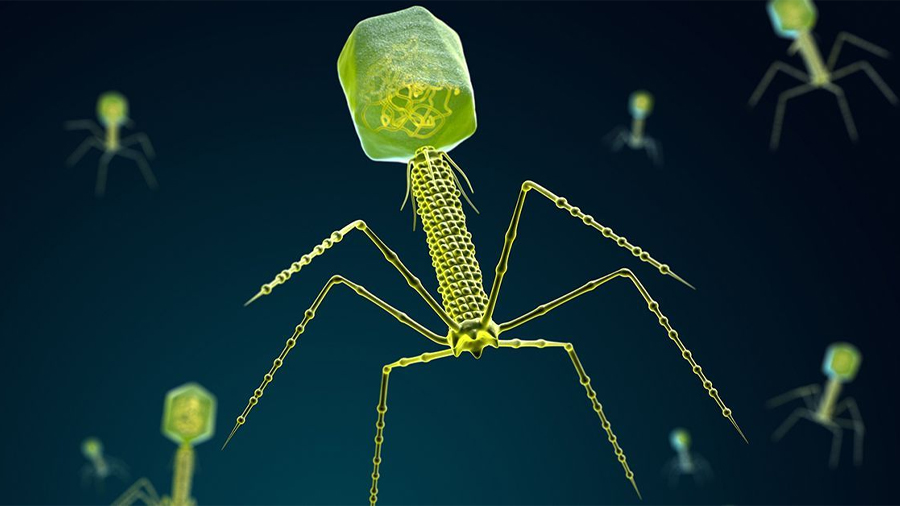

Publishing in the journal Science, researchers in the School of Biological Sciences studied selfish genetic elements in bacteriophages (phages), viruses that are considered the most abundant organisms on Earth. To their surprise, researchers found that selfish genetic elements known as “mobile introns” provide their virus hosts with a clear advantage when competing with other viruses: phages have weaponized mobile introns to disrupt the ability of competing phage viruses to reproduce.

“This is the first time a selfish genetic element has been demonstrated to confer a competitive advantage to the host organism it has invaded,” said study co-first author Erica Birkholz, a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Molecular Biology. “Understanding that selfish genetic elements are not always purely ‘selfish’ has wide implications for better understanding the evolution of genomes in all kingdoms of life.”

Decades ago biologists noted the existence of selfish genetic elements but were unable to characterize any role they play in helping the host organism survive and reproduce. In the new study, which focused on investigating “jumbo” phages, the researchers analyzed the dynamics as two phages co-infect a single bacterial cell and compete against each other.

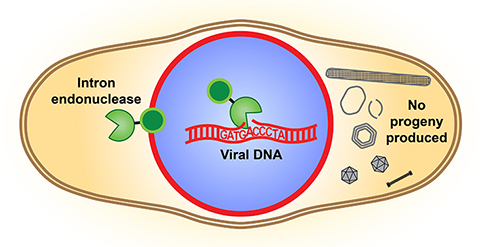

They looked closely at the endonuclease, an enzyme that serves as a DNA cutting tool. The endonuclease from one phage’s mobile intron, the studies showed, interferes with the genome of the competing phage. The endonuclease therefore is now regarded as a combat tool since it has been documented cutting an essential gene in the competing phage’s genome. This sabotages the competitor’s ability to appropriately assemble its own progeny and reproduce.

“This weaponized intron endonuclease gives a competitive advantage to the phage carrying it,” said Birkholz.

The researchers say the finding is especially important in the evolutionary arms race between viruses due to the constant competition in co-infection.

“We were able to clearly delineate the mechanism that gives an advantage and how that happens at the molecular level,” said Biological Sciences graduate student Chase Morgan, the paper’s co-first author. “This incompatibility between selfish genetic elements becomes molecular warfare.”

The results of the study are important as phage viruses emerge as therapeutic tools in the fight against antibiotic resistant bacteria. Since doctors have been deploying “cocktails” of phage to combat infections in this growing crisis, the new information is likely to come into play when multiple phage are implemented. Knowing that certain phage are using selfish genetic elements as weapons against other phage could help researchers understand why certain combinations of phage may not reach their full therapeutic potential.

“The phages in this study can be used to treat patients with bacterial infections associated with cystic fibrosis,” said Biological Sciences Professor Joe Pogliano. “Understanding how they compete with one another will allow us to make better cocktails for phage therapy.”

This article is republished from UC San Diego Today. Read the original here.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Mining microbes for rare earth solutions

Joseph Cotruvo, Jr., will receive the ASBMB Mildred Cohn Young Investigator Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.