Nobelists’ former postdocs discover missing link in telomerase evolution

In 1983, Carol Greider and her Ph.D. advisor, Elizabeth Blackburn, discovered telomerase, the enzyme that replenishes telomeres. For this, they were awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine, and their seminal work opened the gateway for decades of work that has advanced our understanding of aging and human lifespan — including new research by their own former postdocs.

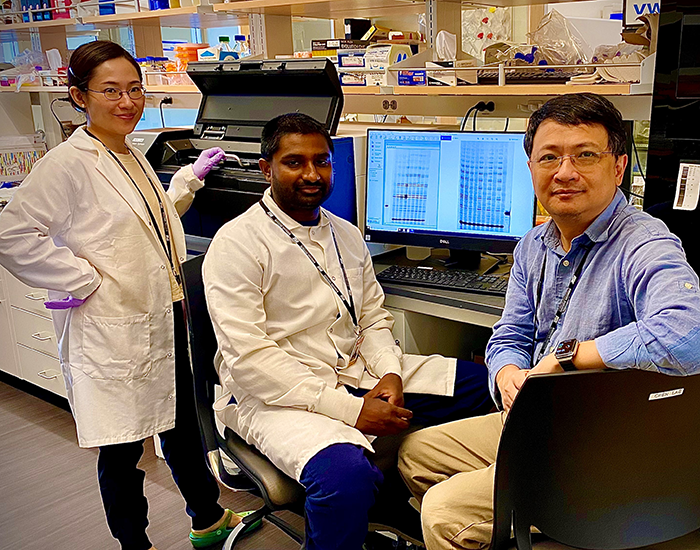

Those postdocs, Dorothy Shippen and Julian Chen, knew each other long before their first collaborative project, a study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Julian and I came out of Carol Greider and Elizabeth Blackburn’s research labs, respectively,” said Shippen, a university distinguished professor and regents fellow in Texas A&M’s department of biochemistry and biophysics. “Due to our similar research interests, we kept crossing paths at various research conferences for many years. Our respective research groups used different tools to answer fascinating questions about telomerase, and Julian and I developed a mutual admiration for each other’s work.”

At the 2019 Cold Spring Harbor Telomeres and Telomerase Meeting, members of Shippen’s group met up with Chen’s lab team (Chen is a professor of biochemistry at Arizona State University) and discussed their ongoing research projects. Those conversations resulted in a collaboration that uncovered a pivotal discovery about telomerase RNA.

About telomerase

Telomeres are repetitive DNA sequences that safeguard the ends of linear chromosomes. Healthy cells have a limited replicative lifespan, and as they age, their telomeres shorten, leading to eventual cellular senescence and/or apoptosis. However, the ribonucleoprotein enzyme telomerase counteracts this shrinking process and helps lengthen telomeres with addition of short DNA repeats, thus extending the life of the cell. The level of telomerase activity is crucial in determining telomere length, particularly in aging cells.

Many researchers have focused on the use of telomerase in cancer and anti-aging treatments. However, much is unknown about the telomerase, particularly its evolution. The enzyme is markedly different across various kingdoms, making it important to understand the components that contribute to these evolutionary differences and their role in telomere maintenance.

Telomerase complexes contain two core components: a catalytic subunit and an RNA subunit. The catalytic protein subunit — telomerase reverse transcriptase — has been well characterized. The RNA subunit serves as a template for the addition of new telomeric repeats by the reverse transcriptase. Researchers first isolated it in 1991 in ciliates and later discovered its homologs in yeast and humans.

Uncovering a missing link

“The telomerase RNA in these three different kingdoms — ciliate, yeast and humans — are very different with regard to transcription machinery, sequence, etc.,” Chen said. “A long-standing question in the telomerase biology field is, how did these various telomerase RNAs evolve so differently?”

Researchers tried for years to isolate telomerase RNA from plant species. They included Shippen, who believed the plant kingdom held the key to unanswered questions in telomerase evolution.

“Plants often evolve unique solutions to fundamental biological challenges,” she said. “Plant telomerases may tell us something new about longevity and aging and how human telomerase could be regulated. Hence, it was essential to discover this missing subunit.”

Shippen previously had identified the reverse transcriptase subunit in plants. In 2019, her team, led by graduate student Jiarui Song, successfully isolated telomerase RNA from the thale cress plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. To isolate this telomerase RNA, termed AtTR, the researchers used a protein purification approach using deep sequencing of RNAs associated with telomerase activity.

“Our investigations began with some genetic and phylogenetic analysis of AtTR,” Shippen said. “We then decided to follow up by further characterizing this subunit and finding new homologs. This is where Dr. Chen and his team played a crucial role.”

Chen and his team worked with the Shippen lab to determine the structure and function of the isolated AtTR and identify its homologs in many other plant species.

These analyses, coupled with studies in cells and animal models, uncovered a startling revelation: The plant telomerase RNA was an intermediate between telomerase RNA from humans and from lower eukaryotes. The subunit contained signature marks from both animal and protist kingdoms.

“We called this intermediate plant telomerase RNA the ‘missing link’ between ciliates and vertebrates,” Chen said. “It significantly expanded our knowledge about telomerase evolution.”

Delving deeper, moving forward

The complete identification of plant telomerase allows researchers to study telomerase evolution in a new way. While ciliate and plant telomerase RNA are transcribed by RNA polymerase III, vertebrate and fungal telomerase RNA are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. How did telomerase RNA evolve to be transcribed by two different RNA polymerases, and how did they make this transition?

To answer this question, Chen said, “Our next step will be to study telomerase RNA in several ancestral plant species to characterize their structure and determine which RNA polymerase they were transcribed by. Hopefully, we will soon have a comprehensive picture about how telomerase RNA has evolved along different eukaryote lineages.”

Shippen wants to delve deeper into the telomerase ribonucleoprotein complex. She believes that a different group of proteins associate with the reverse transcriptase to make it functional in plants.

“By uncovering these accessory components,” she said, “we will gain insight into the interface between the canonical telomerase function and other cellular functions such as metabolism.”

Shippen and Chen will continue collaborating to study plant telomerase. They expect future research into the plant system to have translational application in humans, particularly for cancer and anti-aging treatments.

While plant and human telomerases differ, understanding the plant telomerase mechanism and its evolution might help researchers engineer new strategies to regulate and manipulate human telomerase. For example, higher levels of telomerase immortalize cancer cells, enabling them to live and grow much longer than normal cells. Targeted inhibition of telomerase in cancer might have therapeutic benefit.

Chen and Shippen believe that applications of their findings in humans are years away, but they are optimistic about the future of telomerase research.

“We see a lot of opportunities ahead,” Chen said. “This is indeed an exciting time to be working in the field of telomere biology and telomerase evolution.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.