From the journals: JBC

Myosin mysteries solved. Peculiar PRF processes. Kinesin-3 kicked into high gear. Read about recent papers on these and other topics in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Muscles, myosin and a mechanism mystery

Whether it's the movement of limbs (skeletal muscle), digestion of food (smooth muscle) or the pumping of blood for oxygen delivery (heart muscle), the reliable contraction of muscles is crucial for the physiological processes that support life. Myosins, motor proteins that interact with muscle fibers and generate the forces that drive muscle contraction, must precisely coordinate their mechanical and chemical cycles to execute their biological function properly.

Myosin was first described by Wilhelm Kühne in 1864. Yet, despite over 150 years of studying myosin biology and the mechanisms driving myosin-meditated processes, researchers do not know how myosin converts energy, in the form of adenosine 5'-triphosphate, or ATP, into mechanical work.

To answer this longstanding question, Laura Gunther of Pennsylvania State College of Medicine and a team of biochemists and biophysicists combined single-molecule optical trapping and fluorescence resonance energy transfer, or FRET, technologies. By doing so, the researchers were able to study myosin-related events with near minute-level temporal resolution and observe myosin-related events with unprecedented clarity.

The team found that the myosin's power stroke, the force-generating step when myosin initially interacts with a muscle filament, occurs rapidly, while key biochemical events occur subsequently and more slowly. Using site-directed mutagenesis, they then showed for the first time how communication between actin- and nucleotide-binding regions of myosin is key to coordinating and producing those myosin power strokes.

The researchers present this work in a recent paper in the Journal of Biological Chemistry. Comprehensive knowledge about these processes one day could help scientists produce new treatments for cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders and more.

Crystallizing programmed frameshifting

Programmed ribosomal frameshifting, or PRF, is a tightly regulated mechanism used by certain viruses, including arteriviruses, to produce different proteins encoded by two or more overlapping reading frames within their RNA genome.

Under normal circumstances, ribosomes maintain the reading frame of the mRNA sequence being translated. However, some viral mRNAs carry specific information and structural features in their mRNA molecules that cause ribosomes to slip and then readjust the reading frame. The frame shift results from a change in the reading frame by one or more bases in either the 5′ (−1) or 3′ (+1) direction during translation and enables viruses to encode more proteins in spite of their small size. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, or PRRSV, employs noncanonical PRF mechanisms that are stimulated by the interactions of PRRSV nonstructural protein 1β and host protein poly(C)-binding protein, called PCBP1 or PCBP2 with the viral genome.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Ankoor Patel of the University of Manitoba and colleagues used small-angle X-ray scattering and stochiometric analysis by analytical ultracentrifugation to show how nonstructural protein 1β and PCBP2 interact directly with viral RNA to coordinate this unconventional PRF mechanism.

Chemomechanical oddities of kinesin-3

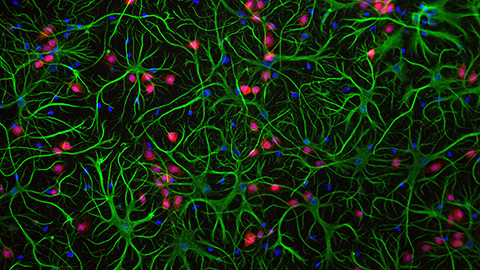

Molecular motors are a class of proteins that hydrolyze adenosine 5'-triphosphate, or ATP, to create the kinetic energy necessary to execute their many biological functions. Unique among these proteins is kinesin-3, which displays the fastest and longest bouts of movement of all kinesins but remains poorly understood.

Using stopped-flow fluorescence spectroscopy and single-molecule motility assays, Taylor Zaniewski of Pennsylvania State University and colleagues uncovered the molecular and biophysical details underpinning kinesin-3's distinctive attributes. The researchers found that hydrolysis of ATP, and not ATP binding, stimulated the forward step of kinesin-3. Their findings showed that the motor protein follows the same chemomechanical cycle as established for kinesin-1 and -2. However, the researchers showed that kinesin-3 differs from kinesin-1 and -2 in three areas: It has a rear-head detachment rate that's an order of magnitude faster than other kinesin family members; its tethered-head attachment transition is rate-limiting; and it has a relatively slow dissociation from the low-affinity, post-hydrolysis state.

These data, published in a recent paper in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, detail the attributes that contribute to kinesin-3's fast and long bouts of movement along microtubules.

Antigens, epitopes and NMR

When epitopes, antibody binding sites present on antigens, are discontinuous, the sequences are recognized only when the protein is folded in a particular conformation. Identification of these epitopes is crucial to understanding immunological mechanisms. However, the characterization of discontinuous antigenic epitopes, such as the lipid transfer polyproteins, or LTPs, in pollen allergens, remains a technical challenge.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Martina Di Muzio and colleagues at the University of Salzburg reported a new approach for studying LTPs involving a modified nuclear magnetic resonance–exchange measurement that detects substoichiometric complexes. In this method, called hydrogen/deuterium exchange memory NMR, a gradual exchange occurs between the invisible antigen–antibody complex and the free 15N-labeled antigen. Using this method, the researchers found three structural epitopes of Art v 3, a pollen LTP from mugwort: two partially cross-reactive regions around α-helices 2 and 4 as well as a novel Art v 3–specific epitope at the C terminus. This new development will be applicable for the study of a wide range of macromolecular interactions.

AggreCounting protein aggregates

The accumulation of misfolded proteins is a pathological feature of several human diseases, including Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Type 2 diabetes. However, researchers have no unifying method to quantify cellular aggregates.

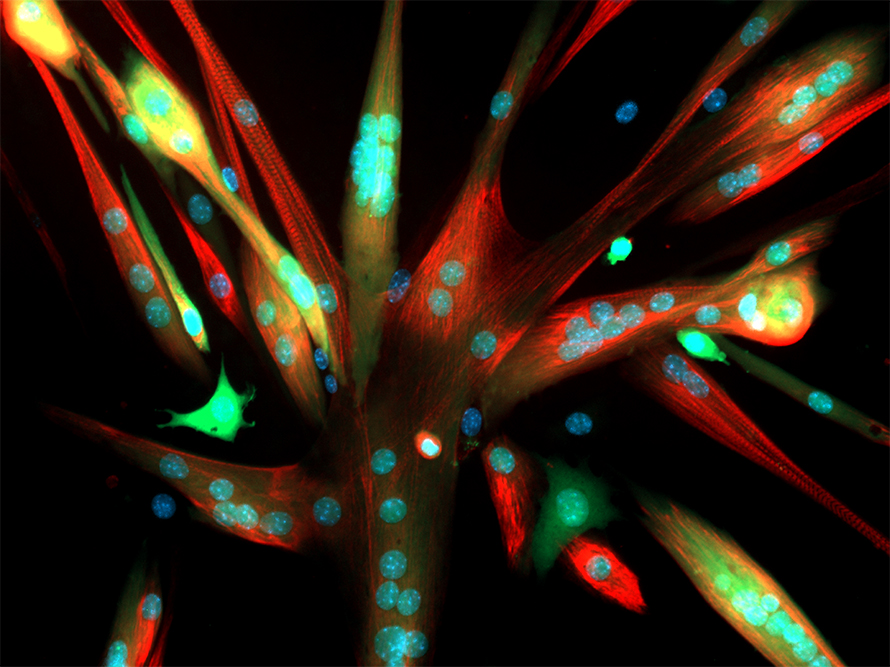

In a recently published paper in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Jacob Aaron Klickstein and colleagues at Tufts University developed an intuitive and easy-to-use macro for the image processing program ImageJ called AggreCount. This tool allows researchers to identify and quantify different types of cellular aggregates in an automated fashion, sparing scientists from the laborious and time-consuming manual counting of protein clumps. The macro, which the researchers have made freely available to all on GitHub, can be applied to multiple cell types for a variety of applications.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

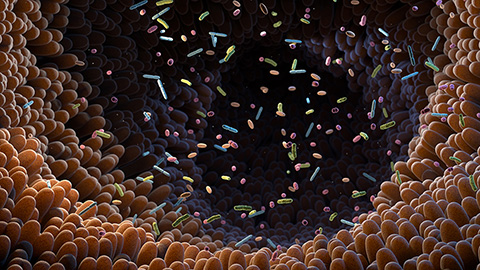

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.