For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

We mark the 150th anniversary of Dimitri Mendeleev’s periodic table of chemical elements this year by highlighting elements with fundamental roles in biochemistry and molecular biology. So far, we’ve covered hydrogen, iron, sodium, potassium, chlorine, copper, calcium, phosphorus, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen and manganese.

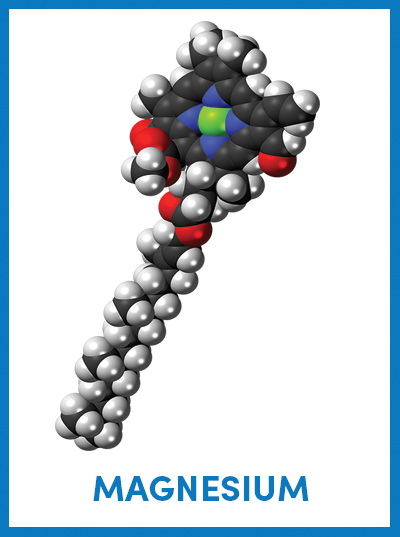

The chemical structure of chlorophyll shows a magnesium ion in green sequestered at the center of a porphyrin ring, which is attached to a long hydrocarbon tail. Jynto/Wikimedia Commons

The chemical structure of chlorophyll shows a magnesium ion in green sequestered at the center of a porphyrin ring, which is attached to a long hydrocarbon tail. Jynto/Wikimedia Commons

October is the month for peak fall foliage in states across the northern and central U.S. Leaves turn yellow, orange and red as chlorophyll — the photosynthetic pigment that gives plants their green color — breaks down due to limited sunlight and cooler temperatures. Chlorophyll consists of a porphyrin ring — a molecule made of carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen — attached to a long hydrocarbon tail. At the center of the porphyrin ring, a magnesium ion stabilizes the chlorophyll molecule and transfers electrons down an electron transport chain to drive the photosynthetic process.

Magnesium — with symbol Mg and atomic number 12 — is a reactive alkaline earth metal that readily can lose two electrons to form a cation with charge +2. In nature, it occurs mostly in compounds with other elements such as carbon, sulfate, oxygen and chlorine.

Magnesium is the ninth most abundant element in the known universe. It is produced in large stars when helium fuses with neon or in supernovas when three atoms of helium fuse sequentially with a carbon nucleus. Supernova explosions disperse magnesium into space, where it falls onto the surface of planets, and into the interstellar medium, where it’s recycled into other star systems.

On Earth, magnesium is the fourth most common element after iron, oxygen and silicon. It is the eighth most abundant element in the Earth’s crust, where it forms large mineral deposits of magnesite, dolomite and other rocks. Magnesium salts easily dissolve in water, making oceans and rivers the most abundant source of biologically available magnesium.

In vertebrates, magnesium is the fourth most common metal ion and the second most abundant intracellular cation after potassium. Protein transporters that carry magnesium across biological membranes must recognize the cation’s large hydration shell and deliver the naked ion. Examples of magnesium transporters are the XntAp protein in the freshwater ciliate Paramecium, the MgtA and MgtB system in the pathogenic bacteria Salmonella, and the SLC41A1 carrier in the plasma membrane of mammals.

Inside the cell, magnesium can be found in the cytosol or stored in intracellular compartments. Free cytosolic Mg+2 alters the cell’s electrical properties by regulating the function of voltage-dependent Ca+2 and K+ channels. This has important consequences in excitable cells such as neurons and muscles, and it regulates processes like neurotransmitter release and muscle contraction and relaxation. Magnesium bound to protein plays a structural role as part of the protein’s conformation or a regulatory role by activating or inhibiting enzyme activity. Magnesium within mitochondria affects the enzymes of energy metabolism and the process of programmed cell death, or apoptosis. And in the nucleus, most of the magnesium is associated with nucleic acids and free nucleotides, neutralizing the negative charge of phosphate groups.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

CRISPR epigenome editor offers potential neurodevelopmental gene therapies

Scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, created a system to modify the methylation patterns in neurons. They presented their findings at ASBMB 2025.

Finding a symphony among complex molecules

MOSAIC scholar Stanna Dorn uses total synthesis to recreate rare bacterial natural products with potential therapeutic applications.

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.