Manganese seldom travels alone

We mark the 150th anniversary of Dimitri Mendeleev’s periodic table of chemical elements this year by highlighting elements with fundamental roles in biochemistry and molecular biology. So far, we’ve covered hydrogen, iron, sodium, potassium, chlorine, copper, calcium, phosphorus, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen.

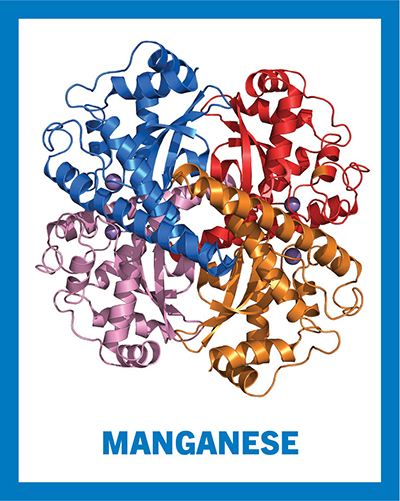

This ribbon diagram represents the structure of the human superoxide dismutase 2 tetramer in coordination with four manganese ions shown in violet.Fvasconcellos/Wikimedia Commons

This ribbon diagram represents the structure of the human superoxide dismutase 2 tetramer in coordination with four manganese ions shown in violet.Fvasconcellos/Wikimedia Commons

For September, we describe manganese, a transition metal with chemical symbol Mn and atomic number 25. Manganese is highly reactive, and it almost never is found as a free element in nature. Rather, it combines with other elements via its multiple oxidation states, which range from +7 to -3. It frequently is found in silicate, carbonate and oxide minerals, and in alloys — compounds containing metals — with iron. People used manganese-containing pigments that are naturally abundant in cave paintings dating back to the Stone Age.

Nuclear reactions that occur in giant stars immediately before supernova explosions produce manganese. It has a short half-life of about 3.7 million years and decays into one of the four chromium isotopes — element variants with different numbers of neutrons. At 0.1%, manganese is the 12th most abundant element on the Earth’s crust. A significant amount of manganese is present on the ocean floor in the form of manganese nodules — specific marine deposits composed by manganese hydroxide and iron.

In living systems, manganese chemistry is restricted to Mn+2 and Mn+3 ions that combine with biological molecules in the aqueous environment of the cell. Mn+2 often overlaps and competes with magnesium and calcium ions as a structural component that stabilizes the net charge of molecules such as proteins and adenosine triphosphate. As a redox cofactor for a large variety of enzymes, manganese is at the catalytic center for cellular reactions that participate in aerobic metabolism.

Manganese is vital to microbial survival. Protein transporters in bacteria break down high-energy chemical bonds in adenosine triphosphate to drive the influx of manganese into the cell from the extracellular environment. Bacterial species of the normal flora of the human digestive and reproductive systems require manganese for survival and growth. The Lyme disease pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi can incorporate manganese in all of its metalloproteins, bypassing host defense by eliminating the need for iron. The diphtheria toxin secreted by the pathogen Corynebacterium contains manganese in its structure. Some bacteria use nonenzymatic Mn+2 ion complexes — generally in combination with polyphosphate — to scavenge reactive oxygen species that are byproducts of cellular metabolic reactions.

In yeast and other eukaryotes, the natural resistance-associated macrophage protein, or NRAMP, family of metal transporters uptake manganese using the driving force of proton gradients. Once inside cells, manganese serves as a cofactor for a multitude of enzymes that include oxidoreductases, carbohydrate-binding proteins such as lectins, and extracellular matrix receptors such as integrins.

Superoxide dismutase, an important manganese-containing enzyme present in mitochondria — and in most bacteria — partitions harmful reactive superoxide ions into molecular oxygen or hydrogen peroxide, protecting cells from the toxicity associated with aerobic respiration. In plants and cyanobacteria, manganese is an essential component of the enzyme responsible for the terminal oxidation of water during the light reactions of photosynthesis.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

CRISPR epigenome editor offers potential neurodevelopmental gene therapies

Scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, created a system to modify the methylation patterns in neurons. They presented their findings at ASBMB 2025.

Finding a symphony among complex molecules

MOSAIC scholar Stanna Dorn uses total synthesis to recreate rare bacterial natural products with potential therapeutic applications.

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.