Addgene expands its collection into antibodies

Scientists often try to ask the same question using two or more independent approaches to reduce the chances that a conclusion could be based on an experimental artifact. Sometimes this might mean using two antibodies against the same target to show that off-target binding isn’t behind an apparent result.

According to Melina Fan, testing an antibody-based result with a second, independent antibody can be trickier than you might think. Because the same antibody is sometimes licensed to several companies, which sell it under different names and catalog numbers, researchers might believe that they’re evaluating results from two independent antibodies when in fact they are looking at the same one twice.

The nonprofit reagent repository Addgene, of which Fan is a co-founder and chief scientific officer, is hoping to solve that problem through radical antibody openness. Addgene, known for distributing some 100,000 plasmids, including fluorescent proteins, CRISPR/Cas9 components and many other gene products, announced in May its plans to partner with NeuroMab, an academic group based in James Trimmer’s lab at the University of California, Davis, which develops antibodies for mammalian brain research.

The Addgene project, dubbed the Neuroscience AntiBody Open Resource, will support conversion of antibody genes from NeuroMab’s collection of nearly 500 hybridoma cell lines into plasmids that encode antibodies, nanobodies and related affinity reagents. Addgene will archive and distribute those plasmids and, starting in 2022, also begin to produce antibodies for sale.

In most mammals, antibodies, which comprise two protein chains, arise through specialized genetic recombination during B cell development, which produces a vast diversity of target-binding sequences. Monoclonal antibodies for research have traditionally been produced by isolating B cells from an animal immunized against a target, then immortalizing those cells to produce a cell line called a hybridoma. More recently, researchers have developed recombinant antibodies, which are encoded on a plasmid that carries both heavy and light chain genes, and can either be developed in vitro or derived from a hybridoma’s antibody genes.

Even though modern technology makes them easier to sequence and characterize, commercial antibodies are often sold in purified protein form, with sequences undisclosed. The scientific community has come to recognize over time that poor-quality antibodies can contribute to irreproducible results. To improve the reliability of research, funders and publishers have begun to request that researchers publish more detail about the tools used in their work, for example by using persistent reagent identifiers indexed with third-party databases. The new project is a further step toward open research.

Funded by the National Institutes of Health's BRAIN initiative, the Addgene effort focuses first on protein targets expressed in the mammalian brain. However, organizers hope that it will expand rapidly into other fields. Addgene already offers 486 plasmids coding for recombinant antibodies, deposited by academic and industrial labs.

“Scientists themselves believe in open science, and this is an opportunity for them to create the research environment that they want to operate in,” Fan said. “We’re hoping that scientists are going to be excited to participate in this resource.”

In response to the announcement on social media, several scientists pointed out that the NIH also funds a hybridoma collection at the University of Iowa, called the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, which has about 5,000 cell lines.

Fan pointed out that since DSHB offers hybridomas, and Addgene will offer recombinant antibodies, the two resources are not in competition. Where efforts might overlap more, she added that Addgene was “open to partnerships with groups that align with our mission and philosophy.”

In general, responses to the news have been enthusiastically positive. Geneticist Neville Sanjana of New York University tweeted, “If Addgene will do for antibodies what it has done for plasmids (both in terms of quality and open sharing), this will be a real game changer.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition weekly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Of genes, chromosomes and oratorios

Jenny Graves has spent her life mapping genes and comparing genomes. Now she’s created a musical opus about evolution of life on this planet — bringing the same drive and experimentalism she brought to the study of marsupial chromosomes.

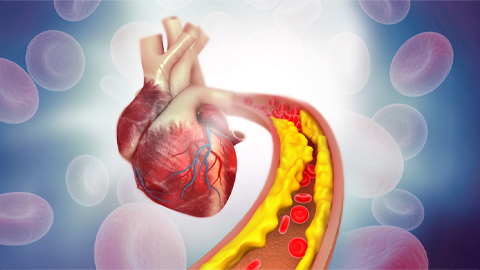

Ubiquitination by TRIM13: An ingredient contributing to diet-induced atherosclerosis

Researchers help unravel the molecular mechanism behind plaque formation in cardiovascular disease.

When ribosomes go rogue

Unusual variations in the cellular protein factory can skew development, help cancer spread and more. But ribosome variety may also play biological roles, scientists say.

New discovery enables gene therapy for muscular dystrophies, other disorders

At the University of Rochester, researchers find that RNA-based technology facilitates effective use for difficult-to-treat, large-gene diseases.

From the journals: JBC

Huntington protein interactions affect aggregation. Intrinsically disordered protein forms a scaffold. From unknown protein to curbing cancer growth. Read about recent JBC papers on these topics.

An inclusive solar eclipse — with outreach

Traveling more than 150 miles with a group of neurodivergent students to have them witness a rare orbital alignment. and also teach the public about it, requires some strategic planning.