For the first time (in cryo-EM): A3G and Vif structure revealed

Lentiviruses, the group of viruses that include HIV, have infected primates for millennia. The coexistence of two parties with opposing interests – in this case, lentiviruses for replication and the host that attempts to evade viral infection – has led to the ongoing battle between the host and virus playing out on a molecular scale over evolutionary time.

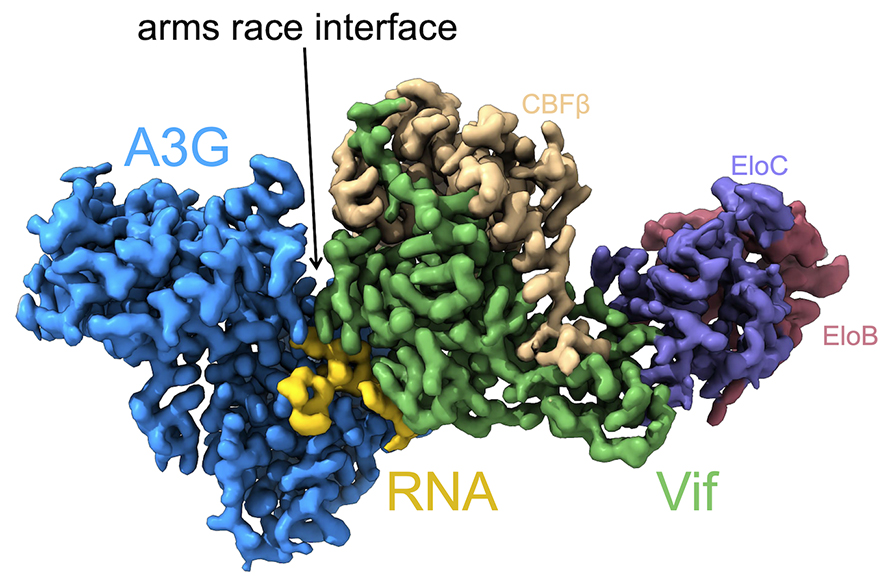

A3G (also known by its longer acronym APOBEC3G) is a protein that prevents HIV from hijacking host cellular machinery to replicate its genetic material. To do this, the A3G protein gets packaged into HIV virions to block viral replication. In turn, the viral protein Vif destroys A3G to prevent it from getting packaged into virions in the first place. Over time, both A3G and Vif have evolved to outsmart each other, resulting in an ongoing molecular arms race.

Scientists have known about A3G and Vif’s molecular arms race for decades, but the structural basis of this interaction remained unknown. In a new study published in Nature, a team of scientists from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center and the University of California, San Francisco reported the first cryogenic electron microscopy structure of human A3G bound to HIV-1 Vif.

“The Vif/A3G story has been at the forefront of the conversation surrounding HIV evolution for over 20 years at this point,” said Dr. Michael Emerman, a professor in the Human Biology and Basic Sciences Divisions at the Fred Hutch and a co-author on the study. “Specifically, mutations in these proteins have given us a quasi-roadmap for how this virus family spilled over into hominids. Though previous work from the Emerman, Gross, and other labs provided crucial insight into the specificities of this protein interface, the structure was something many tried and failed to resolve for the last decade.”

The team behind this paper, including Dr. Yen-Li Li, a postdoc in Dr. John Gross’s lab at UCSF, and Dr. Caleigh Azumaya, the former associate director of the Electron Microscopy Shared Resource at the Fred Hutch, achieved this feat using cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM). This technique utilizes an electron microscope, with a beam of electrons as the source of light, to image samples that have been cooled to cryogenic temperatures. By doing so, cryo-EM can render molecular structures at near-atomic resolution.

“The first thing that jumped out to us was that the ‘arms-race’ interface between A3G and Vif that had been predicted from positive selection analysis was indeed the site of interaction between A3G and Vif,” said Emerman. Positive selection analyses identify specific sites in the protein that have undergone recurrent changes as a result of selective pressures. The selective pressure for A3G, for example, likely results from its antagonizing interaction with Vif. Previous work had identified two such sites in the A3G protein. Moreover, the identity of these sites is known to determine the adaptation of Vif to a new host species. The cryo-EM structure of the site of interaction between A3G and Vif confirmed the prior hypothesis that the region of A3G under positive selection is the site of interaction with Vif.

“The second thing, which was a surprise, is the presence of RNA at the Vif-A3G interface,” said Caroline Langley, a PhD candidate in the Emerman lab and a second author on the paper. The cryo-EM structure revealed a single-stranded RNA molecule at the interface of the Vif and A3G proteins, suggesting that RNA acts as a “molecular glue” that holds the two proteins together.

Like a scientific cornucopia, the cryo-EM structure continued to delight the team with the wealth of information it provided. “It was also a surprise that Vif was bound to an A3G dimer,” said Langley. The ability of A3G to form dimers is critical to its role as a viral restriction factor. If A3G cannot form dimers, it cannot get packaged into virions to carry out subsequent antiviral activities. “In other words, it appears that Vif has evolved to target A3G when it poses the largest threat to viral replication.”

Although cryo-EM provided the structural data, the subsequent analyses of the structure provided much anticipated answers about the evolutionary relationship between Vif and A3G. “This analysis revealed to us that the amino acids in the ‘arms race interface’ are highly variable and species specific. In contrast, the identities of the amino acids identified as binding RNA in the structure were highly conserved, hinting that RNA interaction is evolutionarily important for Vif antagonism of A3G,” said Langley.

This article was first published by the Fred Hutch Cancer Center. Read the original.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.