For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

The International Year of the Periodic Table marks the 150th anniversary of Dimitri Mendeleev’s periodic system. The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology is joining the celebration with a series of articles on biochemical elements. Since January, we have presented hydrogen; iron; sodium, potassium and chlorine; and copper.

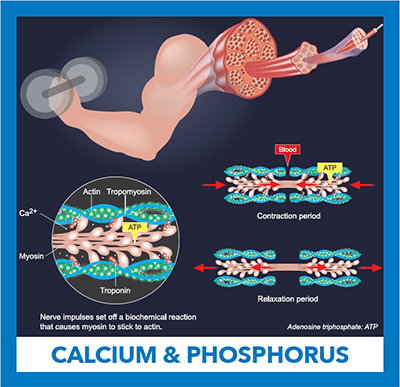

An electrical impulse traveling from a motor neuron results in the release of calcium from the muscle’s intracellular stores. Ca+2 binds to the inhibitory troponin-tropomyosin complex, allowing myosin and actin filaments to slide past one another causing muscle contraction. Adenosine triphosphate is hydrolyzed in the process. Relaxation follows when cytoplasmic calcium is removed.

An electrical impulse traveling from a motor neuron results in the release of calcium from the muscle’s intracellular stores. Ca+2 binds to the inhibitory troponin-tropomyosin complex, allowing myosin and actin filaments to slide past one another causing muscle contraction. Adenosine triphosphate is hydrolyzed in the process. Relaxation follows when cytoplasmic calcium is removed.

May is arthritis awareness month, so we selected calcium and phosphorous, the two components of the mineral salt hydroxyapatite that makes up about 65 percent of the human adult bone mass.

With chemical symbol Ca and atomic number 20, calcium is classified in the periodic table as an alkaline earth metal. In chemical reactions, calcium easily loses the two valence electrons in its outermost orbital to form ionic compounds that contain dipositive Ca+2.

At 3 percent of the Earth crust’s mass, calcium is the fifth most abundant element and the third most common metal after iron and aluminum. Most of the Earth’s calcium is found as a carbonate mineral in limestone — sedimentary rock that contains fossilized sea life. Calcium carbonate makes corals, sea shells and pearls when Ca+2 released by weathering reacts with seawater bicarbonate.

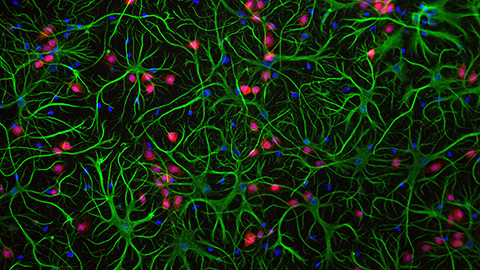

Calcium is essential in biology. Both prokaryotes and eukaryotes maintain low intracellular free Ca+2 via ion channels, transporters and calcium-sequestering proteins. In response to environmental changes, intracellular Ca+2 rapidly rises, transmitting the outside information to the interior of the cell. In bacteria, this calcium signaling system regulates chemotaxis — or movement toward a chemical stimulus — and flagellar rotation.

In mammals, cells respond to hormones by activating the phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling pathway that leads to high intracellular Ca+2 and expression of calcium-dependent genes. Excited neurons release the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, which binds to its receptor on the receiving cell, opening ion channels and allowing the influx of extracellular Ca+2. At synapses, the inflow of calcium propagates the electrical signal to the receiving neuron, and at neuromuscular junctions, it triggers muscle contraction in the receiving fiber.

Phosphorus — with chemical symbol P and atomic number 15 — is a reactive nonmetal that combines with other elements mainly by sharing electrons via covalent bonds. Free phosphorus is rare; the element normally is found in compounds in oxidation states of +3, +5 and -3.

Phosphorus is the 11th most common element on Earth. About one gram of phosphate is found for every kilogram of the Earth’s crust, mostly in the form of oxidized inorganic rocks formed over millions of years.

Phosphorus is required for all life. Some bacteria derive energy for growth by oxidizing H2PO3– or phosphite to inorganic phosphate. Phosphate groups are major structural components of nucleotides, which are the building blocks for nucleic acids like DNA and RNA. Phospholipids — which contain a hydrophobic fatty acid “tail” and a hydrophilic phosphate “head” — form lipid bilayers that constitute cellular membranes.

Most cellular metabolic reactions are driven by chemical energy harnessed from the cleavage of adenosine triphosphate, a molecule that contains a sugar, a nitrogenous base and three phosphate groups. The addition of phosphoryl groups to proteins during phosphorylation changes protein activity and/or cellular localization, regulating a plethora of cell-signaling events.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

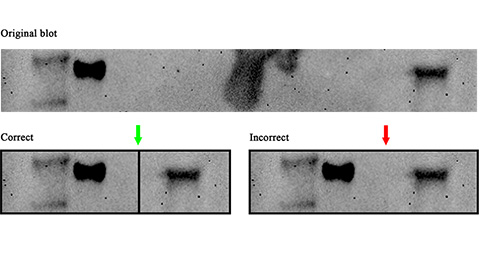

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

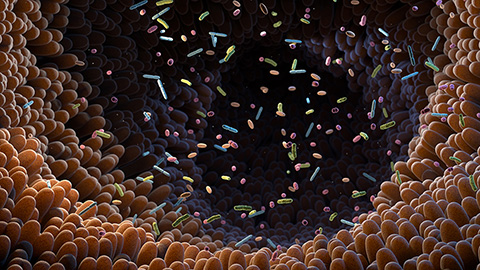

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.