For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

Hemoglobin is a tetramer that consists of four polypeptide chains. Each monomer contains a heme group in which an iron ion is bound to oxygen. In iron-deficiency anemia, the heart works harder to pump more oxygen through the body, which often leads to heart failure or disease.We are celebrating the 150th anniversary of Mendeleev’s periodic table by highlighting one or more chemical elements with important biological functions each month in 2019. For January, we featured atomic No. 1 and dissected hydrogen’s role in oxidation-reduction reactions and electrochemical gradients as driving energy force for cellular growth and activity.

In February, we have selected iron, the most abundant element on Earth, with chemical symbol Fe (from the Latin word “ferrum”) and atomic number 26.

A neutral iron atom contains 26 protons and 30 neutrons plus 26 electrons in four different shells around the nucleus. As with other transition metals, a variable number of electrons from iron’s two outermost shells are available to combine with other elements. Commonly, iron uses two (oxidation state +2) or three (oxidation state +3) of its available electrons to form compounds, although iron oxidation states ranging from -2 to +7 are present in nature.

Iron occurs naturally in the known universe. It is produced abundantly in the core of massive stars by the fusion of chromium and helium at extremely high temperatures. Each of these supergiant, iron-containing stars only lives for a brief while before violently blasting as a supernova, scattering iron into space and onto rocky planets like Earth. Iron is present in the Earth’s crust, core and mantle, where it makes up about 35 percent of the planet’s total mass.

Iron is crucial to the survival of all living organisms. Biological systems are exposed constantly to high concentrations of iron in igneous and sedimentary rocks. Microorganisms can uptake iron from the environment by secreting iron-chelating molecules called siderophores or via membrane-bound proteins that reduce Fe+3 (ferric iron) to a more soluble Fe+2 (ferrous iron) for intracellular transport. Plants also use sequestration and reduction mechanisms to acquire iron from the rhizosphere, whereas animals obtain iron from dietary sources.

Once inside cells, iron associates with carrier proteins and with iron-dependent enzymes. Carrier proteins called ferritins (present in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes) store, transport and safely release iron in areas of need, preventing excess free radicals generated by high-energy iron. Iron-dependent enzymes include bacterial nitrogenases, which contain iron-sulfur clusters that catalyze the reduction of nitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) in a process called nitrogen fixation. This process is essential to life on Earth, because it’s required for all forms of life for the biosynthesis of nucleotides and amino acids.

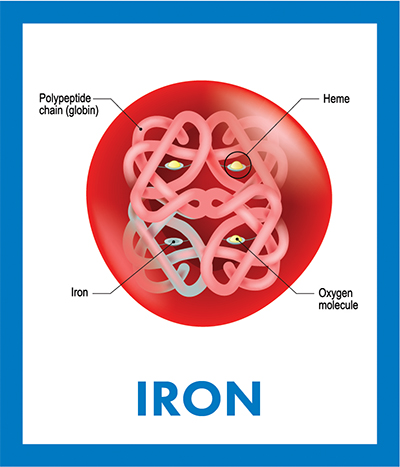

Some iron-binding proteins contain heme — a porphyrin ring coordinated with an iron ion. Heme proteins include cytochromes, catalase and hemoglobin. In cytochromes, iron acts as a single-electron shuttle facilitating oxidative phosphorylation and photosynthesis reactions for energy and nutrients. Catalase iron mediates the conversion of harmful hydrogen peroxide to oxygen and water, protecting cells from oxidative damage. In vertebrates, the Fe+2 in hemoglobin is reversibly oxidized to Fe+3, allowing the binding, storage and transport of oxygen throughout the body until it is required for energy production by metabolic oxidation of glucose.

Living organisms have adapted to the abundance and availability of iron, incorporating it into biomolecules to perform metal-facilitated functions essential for life in all ecosystems.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.