For January, it’s atomic No. 1

Following a proposal initiated by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry and other global scientific organizations, the United Nations has declared 2019 the International Year of the Periodic Table of Chemical Elements, or IYPT2019.

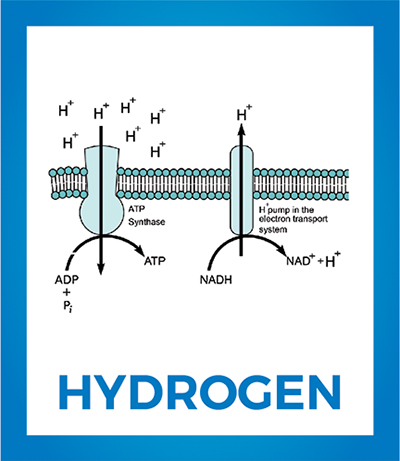

High-energy electrons (from the oxidation of food, for example) passed along the electron-transport chain release energy that is used to pump H+ across the membrane. The resulting electrochemical proton gradient serves as an energy store used to drive adenosine triphosphate synthesis by the adenosine triphosphate synthase. Wikipedia

High-energy electrons (from the oxidation of food, for example) passed along the electron-transport chain release energy that is used to pump H+ across the membrane. The resulting electrochemical proton gradient serves as an energy store used to drive adenosine triphosphate synthesis by the adenosine triphosphate synthase. Wikipedia

The designation commemorates the 150th anniversary of the first publication of Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev’s periodic table in 1869. Mendeleev’s table was not the first attempt to arrange the just over 60 chemical elements known at the time, but it was the first version to predict the existence of unidentified elements based on the periodicity of the elements’ physical and chemical properties in relation to their atomic mass.

Today’s periodic table contains at least 118 confirmed elements; of these, only about 30 are essential to living organisms. Bulk elements such as hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen and oxygen are abundant structural components of cells and tissues, whereas trace elements (iron, zinc, copper and magnesium, for example) occur in minute amounts as enzyme cofactors and stabilizing centers for protein complexes.

To celebrate IYPT2019, we are launching a yearlong series that features at least one monthly element with an important role in the molecular life sciences.

Hydrogen

For January, we selected the first element of the periodic table, hydrogen, whose atomic number 1 indicates the presence of a single proton in its nucleus. Hydrogen can occur as a single atom designated as H, as diatomic gas, or H2, in molecules such as water or natural organic compounds (such as carbohydrates, lipids and amino acids) or as negative or positive ions — H- or H+, respectively — in ionic compounds.

Living organisms use hydrogen in oxidation-reduction, or redox, reactions and electrochemical gradients to derive energy for growth and work. Microbes can uptake H2 from the environment and use it as a source of electrons in redox interconversions catalyzed by enzymes called hydrogenases. The transfer of electrons between H2 and acceptor molecules generates H+, and it’s accompanied by substantial energy changes that can be used for cellular metabolism such as synthesis of molecules, cell movement and solute transport.

Cells also use H+ to generate energy from the breakdown of foods such as sugars, fats and amino acids in a process called cellular respiration. In a cascade of metabolic reactions, nutrients like glucose are oxidized and split into smaller molecules, yielding reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, or NADH, and reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide, or FADH2 as biochemical intermediates.

Under aerobic conditions, a series of proteins that comprise the electron transport chain transfer electrons from NADH and FADH2 to cellular oxygen while pumping H+ across a membrane. This process generates a strong H+ electrochemical gradient with enough force to drive the activity of the adenosine triphosphate synthase, resulting in biochemical energy production as the gradient dissipates.

The potential energy in H+ gradients can be used to generate heat for thermogenesis in the brown fat tissue of hibernating mammals, to power flagellar motors in bacteria, to transport nutrients into cells or to generate low pH inside vacuoles. These examples highlight the ubiquitous role of a single element — hydrogen — in essential-for-life biochemical reactions across multiple kingdoms.

A year of (bio)chemical elements

Read the whole series:

For January, it’s atomic No. 1

For February, it’s iron — atomic No. 26

For March, it’s a renal three-fer: sodium, potassium and chlorine

For April, it’s copper — atomic No. 29

For May, it’s in your bones: calcium and phosphorus

For June and July, it’s atomic Nos. 6 and 7

Breathe deep — for August, it’s oxygen

Manganese seldom travels alone

For October, magnesium helps the leaves stay green

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.