Can a hair-loss drug prevent heart disease?

Drug discovery is costly and filled with uncertainty. Drug repurposing reduces time and costs by identifying new applications of a drug already approved or under investigation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The FDA approved finasteride, under the brand name Proscar, in 1992 to treat benign prostate enlargement in men and again, in 1997, under the brand name Propecia, to treat male pattern hair loss.

Researchers at the University of Illinois Urbana–Champaign, U of I, recently found another potential use for finasteride: preventing cardiovascular diseases, or CVD. In a study published in the Journal of Lipid Research, the team hypothesizes that finasteride will lower heart disease risk by cutting cholesterol levels.

The researchers studied the effects of finasteride on male mice and analyzed data from men who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, or NHANES, between 2009 and 2016.

Finasteride is a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor that prevents the conversion of testosterone into dihydrotestosterone, or DHT, an active metabolite that plays a critical role in forming male sex organs, hair patterns and prostate growth.

Donald Molina, a graduate student at U of I and first author of the study, explained that low levels of testosterone in men are associated with higher CVD risk.

“As the drug acts on the levels of testosterone, we thought there might be an association between the drug and heart disease,” he said. “This was our starting point; we investigated how finasteride affected lipid profiles in humans.”

The team first analyzed the data deposited at NHANES and found that finasteride intake was associated with a reduction in total cholesterol and low-density cholesterol.

“These results encouraged us to go for the animal studies,” Molina said.

The researchers used male mice genetically predisposed to atherosclerosis, a major underlying cause of heart disease. They fed the mice a high-fat, high-cholesterol diet for 12 weeks, and finasteride was administered in four increasing doses. They monitored cholesterol and other lipid levels and studied gene expression and lipid metabolome.

The mice on finasteride had lower cholesterol levels and showed delayed progression of atherosclerosis, reduced plasma triglycerides and less liver inflammation.

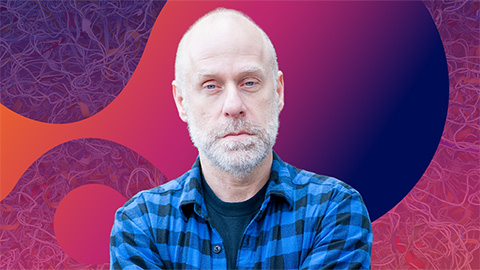

Jaume Amengual, an associate professor at U of I and lead author on the study, said the team thinks that, in the presence of finasteride, the liver degrades more lipids.

“The liver is burning more fat,” Amengual said. “We can also relate our findings to fatty liver disease. When you have a bad diet, you have a lot of fat accumulating in your liver, your liver will become inflamed and eventually develop into liver cirrhosis and even cancer. Therefore, we see in our experiment a decrease in the fat content in the liver and decreased liver inflammation. Not only did finasteride reduce levels of plasma cholesterol, it also improved how the liver was working in these mice.”

To bolster these findings, the researchers will need a detailed analysis of the effects of finasteride on a statistically relevant population and metabolic side effects such as levels of gut microbiota, as well as studies of its interactions with other drugs that target cholesterol synthesis or absorption.

“One of the reasons why I became interested in this medication in the first place is because I have been taking this drug for hair loss since I was about 20,” Amengual said. “Even with limitations our study offers a stepping stone for repurposing finasteride for preventing cardiovascular diseases.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Fasting, fat and the molecular switches that keep us alive

Nutritional biochemist and JLR AE Sander Kersten has spent decades uncovering how the body adapts to fasting. His discoveries on lipid metabolism and gene regulation reveal how our ancient survival mechanisms may hold keys to modern metabolic health.

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Mining microbes for rare earth solutions

Joseph Cotruvo, Jr., will receive the ASBMB Mildred Cohn Young Investigator Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Fueling healthier aging, connecting metabolism stress and time

Biochemist Melanie McReynolds investigates how metabolism and stress shape the aging process. Her research on NAD+, a molecule central to cellular energy, reveals how maintaining its balance could promote healthier, longer lives.

Mapping proteins, one side chain at a time

Roland Dunbrack Jr. will receive the ASBMB DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.