How do diet and lipoprotein levels affect heart health

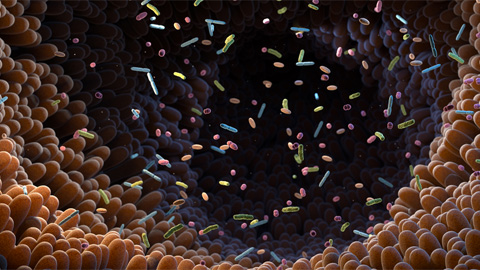

Cardiovascular diseases are among the leading causes of death globally, taking an estimated 17.9 million lives each year. An important risk factor of heart disease is an unhealthy diet leading to overweight and obesity, high blood pressure and increased levels of glucose and lipids in blood. Drugs that help manage body weight have clinical value but do not help prevent premature deaths. Hence, scientists seek ways to identify and treat individuals at higher risk of heart disease.

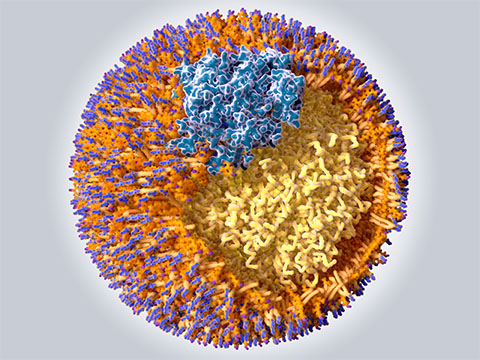

Increased levels of triglycerides and small low-density lipoproteins, or LDL, and low level of high-density lipoproteins, or HDL are markers of atherogenic dyslipidemia, a metabolic condition that builds plaques in the arteries, leading to heart diseases. Previously, cross-sectional studies have shown a correlation between high triglyceride levels and soluble LDL receptor, or sLDLR.

Ronald Krauss and his group at the University of California, San Francisco in collaboration with Christopher Gardner’s team in Stanford University recently showed dynamic changes in lipids and lipoproteins in conjunction with sLDLR; the study was published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

Krauss is interested in understanding the mechanisms regulating plasma lipoprotein metabolism that may impact cardiovascular disease risk and discovering sLDLR as an important component that impacts it. The Krauss lab uses ion mobility analysis to subdivide fractions of various densities of lipoproteins into narrow intervals of their respective subclasses. His team used this technique to study the correlation between lipoprotein particles and cardiometabolic risk, a lipid measure of heart disease risk.

Gardner provided samples from Diet Intervention Examining the Factors Interacting with Treatment Success, or DIETFITS, a study in which people were given either a healthy low-fat or low-carbohydrate diet to determine how lipid and lipoprotein fractions influence cardiometabolic risk. The researchers investigated the cross-sectional and longitudinal relationship of lipids, lipoproteins related to the level of sLDLR and triglyceride with a baseline of six months.

According to Krauss, using principal component analysis, his team showed that the level of sLDLR is tightly regulated to these other lipid measurements. The study population was limited, so this study must be replicated to make generalizations about the conclusions.

It has already been shown that he protease, membrane type 1–matrix metalloproteinase, or MT1-MMP, cleaves the ligand binding domain of sLDLR capable of binding to very low-density lipoprotein, or VLDL, and LDL particle and increases the level of sLDLR in plasma.

“The work is clinically and scientifically important for developing new therapeutic approaches to either target the protease and/or other mechanisms to inhibit the cleaving of LDLR,” Krauss said. “As the free domain of LDLR circulating in plasma acquires new function by binding to VLDL, mechanisms to directly stop the association of LDLR with VLDL could also be potential measurement to lower the atherogenic dyslipidemia.”

Krauss said the study opens new avenues to explore “how the soluble LDLR achieves this new feature by unknown conformational changes.”

“MT1-MMP is thought to be activated by unknown inflammatory signaling pathways,” he said, “which also needs further investigation along with its mode of interaction with sLDLR.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Meet Donita Brady

Donita Brady is an associate professor of cancer biology and an associate editor of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, who studies metalloallostery in cancer.

Glyco get-together exploring health and disease

Meet the co-chairs of the 2025 ASBMB meeting on O-GlcNAcylation to be held July 10–13, 2025, in Durham, North Carolina. Learn about the latest in the field and meet families affected by diseases associated with this pathway.

Targeting toxins to treat whooping cough

Scientists find that liver protein inhibits of pertussis toxin, offering a potential new treatment for bacterial respiratory disease. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Elusive zebrafish enzyme in lipid secretion

Scientists discover that triacylglycerol synthesis enzyme drives lipoproteins secretion rather than lipid droplet storage. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Scientists identify pan-cancer biomarkers

Researchers analyze protein and RNA data across 13 cancer types to find similarities that could improve cancer staging, prognosis and treatment strategies. Read about this recent article published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

New mass spectrometry tool accurately identifies bacteria

Scientists develop a software tool to categorize microbe species and antibiotic resistance markers to aid clinical and environmental research. Read about this recent article published in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.