Making progress on Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Duchenne muscular dystrophy, the most common form of muscle-wasting disease, is a genetic disorder caused by alterations of a protein called dystrophin. Dystrophin acts as a shock absorber in muscles. It protects muscles in the body as they contract and relax. DMD patients damage themselves every time their muscles contract.

The onset of DMD is usually between ages 2 and 3. It affects primarily boys. In Europe and North America, about six of every 100,000 people have DMD. The disease becomes fatal when the heart and breathing muscles deteriorate.

Today is Duchenne Awareness Day. This observance article covers the causes and effects of the disease as well as how biomedical research is helping to improve patients’ lives.

What causes DMD?

DMD is named after the French neurologist Guillaume-Benjamin-Amand Duchenne, who in 1861 first described it in a book about a boy with it. Nearly a century later, in 1987, dystrophin was identified by Louis M. Kunkel and the DMD gene was characterized by Robert G. Wonton.

The dystrophin gene is the largest gene identified in humans and is located in the short arm of the X chromosome, in the Xp21.2 locus. The types of mutations include:

-

Large deletions: One or more exons missing from the gene.

-

Large duplications: One or more exons with extra copies in the gene.

-

Other changes: Small changes, such as tiny deletions or changes in a single letter in the genetic code.

A majority of DMD patients have a deletion in one or more exons. The most common mutation in people with Duchenne is a deletion of one or more exons. Like the puzzle pieces, these missing exons prevent the remaining exons from fitting, affecting the body’s ability to produce functional dystrophin.

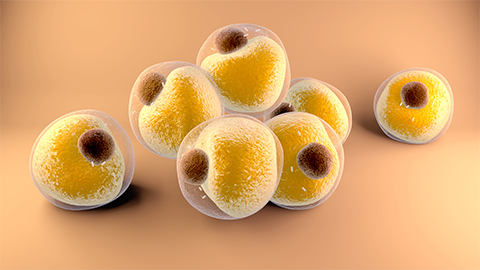

DMD patients make less than 5% of the normal quantity of dystrophin needed for healthy muscles and as they age their muscles cannot replace the dead cells. The dead cells in muscles gradually get replaced by connective and adipose tissue.

Inheritance in DMD

DMD is an X-linked recessive inheritance. A son born to a woman with DMD has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutated gene, while a daughter has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation and being a carrier for it. Carriers may not have any disease symptoms but are at risk of cardiomyopathy.

The mutated gene is not passed from a father to his son, but it is passed to his daughters, making them carriers.

About 30% of cases happen with no apparent family history. In those cases, the mutation existed in the women of the family and it was not diagnosed, or the child with DMD had a new genetic mutation that arose in the mother’s egg.

Diagnosis

When a child exhibits DMD symptoms, medical practitioners investigate the family history and perform a physical exam, neurological exam and muscle exam.

The following diagnostic tests are usually recommended:

-

Creatine kinase blood test: Damaged muscles release creatine kinase, so elevated levels may indicate DMD. Around age 2, the levels peak and can be more than 10 to 20 times above the normal range.

-

Genetic blood test: This looks for a complete or near-complete absence of the dystrophin gene, confirming the diagnosis of DMD.

-

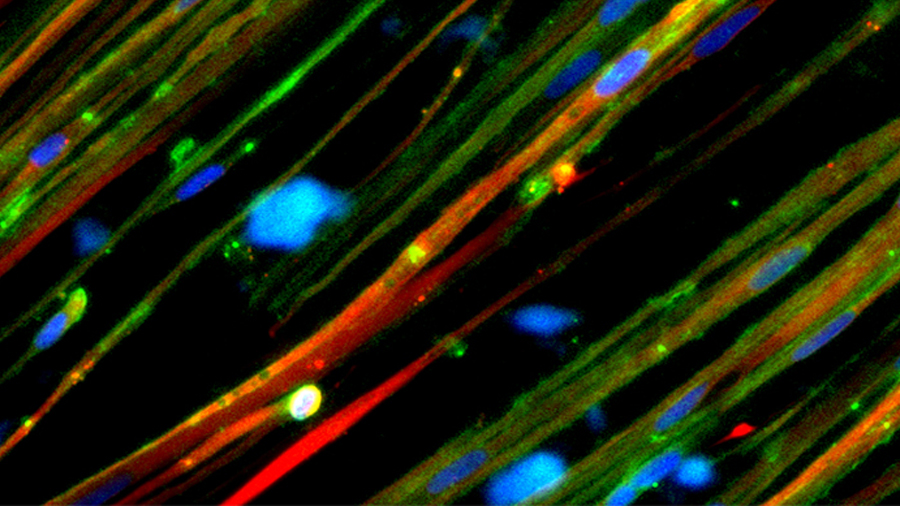

Muscle biopsy: Microscopic examination of the muscle tissue is done to detect signs of DMD.

-

Electrocardiogram: This examines the heart muscles that are the first to be affected in DMD and assesses heart health.

Treatments and promising breakthroughs

Conventional DMD treatments manage symptoms and improve patients' quality. Corticosteroids delay muscle wasting, improve lung function, delay scoliosis and slow the progression of cardiomyopathy. Exercise and physical therapy are used to stave off muscle atrophy.

The lack of dystrophin in DMD makes the muscles weak. Scientists, therefore, are developing complementary therapies that will replace the nonfunctional dystrophin with a functional form to promote muscle repair and growth.

In June, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first gene therapy for 4- and 5-year-old children with DMD. Elevidys is a recombinant gene therapy designed by Sarepta Therapeutics. It delivers a gene with the minimum amount of information from the dystrophin gene needed to produce a functional protein, termed microdystrophin. It is a shortened protein of 138 kDa, compared with the 427 kDa dystrophin protein of normal muscle cells. The shortened gene is packed into harmless viruses for delivery to muscle cells as a single intravenous injection.

Scientists are also developing strategies to alter how genetic instructions are read. Exon skipping allows the production of partially functional dystrophin, which lessens the severity of muscle weakness in DMD but does not completely fix the muscles. In 2016, the FDA approved Exondys 51 to target exon 51 in the mutated dystrophin gene, which affects about 13% of patients with DMD.

Other potential treatments still in development are aimed at promoting muscle growth and repair, accelerating muscle repair, combating muscle inflammation, blocking muscle fibrosis, maximizing blood flow to muscles and protecting the heart.

Closing in on a cure

This 2019 cover story, written after the rollout of exon-skipping drugs that cost $300,000 a year, explores research focused on delivering corrections using compacted genes and CRISPR–Cas9. It asks: What is the future of treating this most common form of muscular dystrophy?

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.

Melissa Moore to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.