MCP: Study shows long-term effects of weight loss on the proteome

As hard as weight loss is, long-term maintenance can be even more of a challenge. But research published in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics indicates that the hard work of maintaining weight loss can pay previously unknown health dividends.

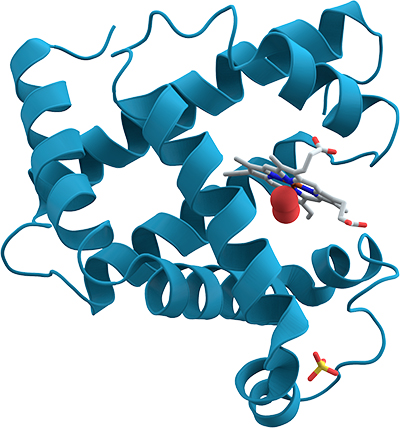

Proteomics researchers found that many plasma proteins, such as myoglobin, shown at left, increase in nonenzymatic glycation after patients lose weight. It takes six months to a year of sustained weight loss for glycation to drop below baseline levels. PDB / S.E. Phillips

Proteomics researchers found that many plasma proteins, such as myoglobin, shown at left, increase in nonenzymatic glycation after patients lose weight. It takes six months to a year of sustained weight loss for glycation to drop below baseline levels. PDB / S.E. Phillips

Using plasma samples from a study that followed people as they lost weight and worked to keep it off, researchers at a Swiss proteomics company called Biognosys, in collaboration with a team at Nestlé, studied how weight loss affected participants’ blood proteome. They observed that while chronic inflammation subsides immediately after weight loss, it takes some time for added beneficial effects to kick in.

The diet, obesity and genetics study, or DiOGenes for short, was designed to test the benefit of various diets in maintaining weight loss. Among the 550 participants who lost 8 percent or more of their starting weight and stayed in the study for another six months, researchers reported in 2010, those who followed a high-protein, low-glycemic-index diet were most successful at keeping it off.

More recently, researchers at Biognosys led by Lukas Reiter used a streamlined proteomics approach to analyze patient plasma samples from the start of the study, the end of its eight-week weight-loss phase, and six and 12 months into the maintenance phase. Consistent with other weight-loss studies, the team saw a dramatic, lasting drop in inflammatory signaling linked to atherosclerosis and an increase in lipid metabolism soon after weight loss.

Because of the depth of their proteome coverage, the Biognosys researchers could add a look at protein glycation. Nonenzymatic glycation occurs when high concentrations of sugar react with proteins in the plasma. Many of the glycated proteins that changed significantly during weight loss, including albumin, myoglobin and some apolipoproteins, were unexpectedly more abundant after the study’s initial weight-loss phase. It took more than six months on the weight-maintenance diet for those glycated proteins to drop back below their baseline levels. Because glycated proteins can activate the immune system, the researchers wrote, the effect of longer-term weight loss is positive.

In future studies, the researchers who own the data hope to move from looking at the whole cohort’s proteome to correlating each study participant’s outcomes with the composition of that individual’s proteome at baseline in search of biomarkers that could help predict how future dieters will fare. Meanwhile, the Biognosys team wants to use its analytic abilities to power high-throughput proteomics for clinical trials.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.