Rare Disease Day

Rare Disease Day is Feb. 28. To mark this important health observance, the ASBMB is sharing throughout the month research and stories about living with, treating and investigating the underlying biological mechanisms of rare diseases and disorders.

What do we mean by rare?

To be classified as rare in the United States, a disease or disorder must affect fewer than 200,000 people. In Europe, it must affect fewer than 1 in 2,000. Rare diseases sometimes are called orphan diseases. The National Organization for Rare Disorders keeps a rare disease database and welcomes additions from experts. See the database here.

What are the causes?

Most rare diseases are genetic in origin, though at least one-fifth of them are caused by infections, allergies and/or the environment. Of course, it’s not always cut and dry. For example, some people may be born genetically predisposed to certain types of disease, such as autoimmune disease, which tends to run in families, and later in life come into contact with environmental pollutants and/or pathogens that set forth disease processes. This is why, for example, researchers at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences are studying how “environmental exposures, individually and in combination, cause or modify inflammation, along with what genetic and other susceptibility factors influence the inflammatory response.”

What don’t we know?

There’s still a lot to be learned about the 7,000 known rare diseases, and there are many barriers to filling in those blanks.

To begin with, a proper diagnosis is often long in the making. As William R.H. Evans and Imran Raji put it, “Patients frequently describe a long and protracted ‘diagnostic odyssey,’ taking years, or even decades.” Understandably, most general practitioners aren’t walking rare-disease encyclopedias, and, to make matters worse, the same rare disease can manifest in different patients in different ways.

Once patients do secure accurate diagnoses, they may not have many treatment options and may end up resorting to the use of therapies designed to treat related conditions or those that simply alleviate some of the symptoms rather than addressing the actual causes. Indeed, upwards of 95 percent of rare diseases have no therapies approved specifically for them by the Food and Drug Administration.

What should we know?

That rare disease patient care can be very expensive. For starters, there’s low demand for orphan drugs, so they are not sold at low prices. “Recouping research and development costs from a small patient population is harder compared to drugs developed for common conditions,” explains the National Gaucher Foundation. “As a result, drugs for rare diseases, including Gaucher disease, are generally priced much higher than medications for common conditions.” Even if a doctor prescribes a drug for an insured patient, there’s no guarantee that the patient’s insurance provider will cover it, sometimes putting life-saving drugs out of reach for those patients who can’t afford the out-of-pocket costs. Pharmaceutical companies sometimes provide eligible patients with discounts. Clinical trials also give eligible patients access to medications being studied, not all of which are brand new — just new for those diseases. Aside from drugs, there are many other care expenses to be considered, such as assistive medical equipment, health-monitoring equipment, housing modifications, in-home care services, and employment instability, among others.

Below are our stories and research highlights for Rare Disease Day. We hope you will join us on Twitter in sharing information about rare disease patients’ critical unmet needs and the research that is giving them hope. Use the hashtag #RareDiseaseDay.

A mother’s letter to biomedical researchers

Lilly Grossman in 2006

Lilly Grossman in 2006

E. Gay Grossman's little girl, Lilly, has a rare disease about which almost nothing is known. Read her appeal to scientists.

Passionate parents catalyze research

A mother and a researcher co-wrote this tale about how serendipitous meetings and basic biochemistry accelerate the push for a cure for the rare and fatal Lafora disease.

A medical detective story

Doctors in Israel were treating a baby with an ultra-rare myelin deficiency. Researchers in Japan had studied the mutation that caused it. Find out how they were brought together.

Team effort to figure out a rare disease

A medical geneticist used whole-exome sequencing of a 17-year-old girl and her parents to reveal a mutation responsible for a rare genetic disease. Then she put together a team of strangers to move research on the mutation forward.

Gene therapy shows promise for deadly childhood disorder

Sandhoff disease disrupts an enzyme that breaks down gangliosides, complex lipids that then accumulate to cause cell death in the brain and spinal cord. Researchers created stem cells with and without corrected copies of the affected gene to study how the disturbed enzyme affects early development.

A close-up of the lipids in Niemann-Pick disease

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago used mass spectrometry imaging to map the lipid accumulation that leads to neurodegeneration and early death in this rare genetic disorder. Read more about the study.

Changing the face of a rare disorder

Keutel syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that leads to overcalcification in cartilage, can cause craniofacial malformations but it is not yet clear exactly how. Researchers from McGill University reported in the Journal of Biological Chemistry that deficiency of matrix Gla protein (MGP), which is mutated in Keutel syndrome, caused midface hypoplasia in mice. By transgenically restoring MGP expression, the researchers completely prevented development of craniofacial anomalies in mice.

Searching for a rare cancer’s “fingerprints”

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is a rare and often asymptomatic cancer that is difficult to identify in patients. To identify biomarkers for improved detection, researchers examined GIST exosomes, nanosize vesicles secreted by the tumors. Using quantitative proteomic profiling, they identified more than 1,000 exosome proteins that could signify a unique “fingerprint” for GIST and help clinicians detect tumors. These findings were reported in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

They’re called “butterfly babies”

Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa has been called the worst disease you’ve never heard of. Caused by mutations in the COL7A1 gene, which makes proteins to assemble type VII collagen, DEB results in especially delicate skin — so delicate its young patients are called “butterfly babies.” Indeed, a wipe of the mouth or bottom will leave an open wound. The painful blistering and scarring is just the start; these patients are likely to die of skin cancer before they’re 40. In a paper published in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, researchers recently showed that C7 loss in keratinocytes, the main cells of the epidermis, elicits a wound-healing response and allows fibrosis to develop. The study also identified strong upregulation of pro-inflammatory proteins, S100A8 and S100A9, which the authors suggest could make promising drug targets for treating DEB.

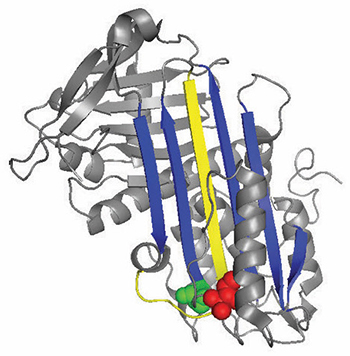

A ribbon diagram of antithrombin

A ribbon diagram of antithrombin

A rare blood disease can teach us about blood clotting

The protein antithrombin is responsible for stopping coagulation. About one in 2,000 people have a hereditary deficiency in antithrombin that puts them at much higher risk of life-threatening blood clots. Researchers recently analyzed the mutations in the antithrombin proteins of these patients and discovered something that could lead not only to treatments for patients with antithrombin deficiency, but also to better-designed drugs for other blood disorders.

A skin deep study

Mutations in the PHGDH gene can lead to Neu-Laxova syndrome, a rare congenital disorder that causes severe growth delays and disrupts skin and central nervous system development. About half of the affected infants have dry, yellow patches of skin — a condition called ichthyosis. Researchers recently examined the skin of NLS patients, revealing a large decrease in ceramides, a waxy substance normally highly concentrated in skin. They determined this loss of ceramides as the likely cause of ichthyosis. They reported their results in the Journal of Lipid Research.

Lipid-based therapy

In patients with adult polyglucosan body disease (APBD), a mutation prevents glycogen branching enzyme 1 (GBE1) from doing its job. This causes aggregation of glycogen in the nervous system which can lead to motor dysfunction and loss of bladder control. In this paper in the Journal of Lipid Research, researchers designed and tested new lipids called triacylglycerol mimetics (TGMs) for potential APBD therapy. Interactions between the TGMs and GBE1 unveiled that some of the drugs could both greatly improve functionality and stabilization of the mutant protein.

A target to reduce lung surfactant

Surfactant, a slippery substance that lowers surface tension, coats the inside of your lungs, allowing them to expand. However, when surfactant isn’t cleared appropriately, it can disrupt breathing, as in the rare lung syndrome called pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. In a study published in the Journal of Lipid Research, researchers reported that mice deficient in ABCG1 protein accumulated surfactant the way PAP patients do. DNA sequencing of lung fluid from PAP patients also revealed genetic polymorphisms in the ABCG1 gene, further emphasizing this protein as a key player in PAP.

Protein turnover key in neurological disease

Alexander disease is a rare and deadly neurological condition marked by pathologic buildup of mutated glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in the nervous system. Many researchers have presumed that GFAP would degrade slowly in affected cells, but in a paper published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, researchers reported that they had discovered just the opposite. By comparing GFAP in diseased and healthy mice, they determined that the mutant protein degrades much faster. The study suggests that the mutation behind Alexander disease increases GFAP turnover rate, a finding that will aid development of strategies to manage or prevent GFAP accumulation.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.

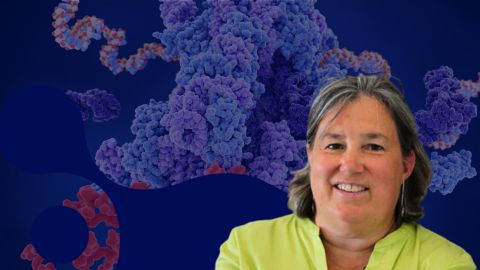

Melissa Moore to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.