MCP: When mitochondria make B cells go bad

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or B-CLL, is the most common type of leukemia in adults and primarily affects elderly patients. The disease results from a patient’s bone marrow overproducing immature lymphocytes, a form of white blood cells that fight infections less effectively than their healthy counterparts but survive longer, ultimately overwhelming them and spreading unchecked. Unlike acute leukemia, B-CLL can take several years to cause problems for a patient, but it is less responsive to chemotherapy.

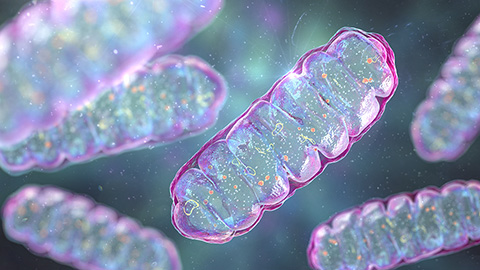

When mitochondria, highlighted here in cow cells, suffer age-related oxidative damage, they can give rise to chronic lymphocytic leukemia.courtesy of Torsten Wittmann, University of California, San Francisco

When mitochondria, highlighted here in cow cells, suffer age-related oxidative damage, they can give rise to chronic lymphocytic leukemia.courtesy of Torsten Wittmann, University of California, San Francisco

While novel treatments have been developed in recent years, they only target the B cells once they’ve mutated to an immature, cancerous state. To develop treatments for B-CLL that might prevent B cells from becoming cancerous in the first place, researchers led by Christopher Gerner at the University of Vienna and Vienna Metabolomics Center have performed a comprehensive proteomics analysis of B-CLL cells and mature B cells in young and elderly patients. They described their work in a paper in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics.

“It could be nice to not only target the cancer cells, but those cells prone to becoming cancer cells,” Gerner said. “What we actually saw when we compared the young and the elderly donors was a very clear signature of mitochondrial stress and metabolic stress.”

Gerner and colleagues found that B-CLL cells have an increased expression of stem cell-associated molecules and a reduced expression of tumor-suppressing molecules and stress-related serotonin transporters as well as an observed increase in glutamine consumption and beta-oxidation of fatty acid.

This indicated that reactive oxidative species, which are carcinogenic and cause damage to cells, were being upregulated, Gerner said, which would explain why the incidence of mutations that lead to B-CLL increases with age. The researchers hope that the alterations in regulation also may provide a proteomic signature for immunosenescence, the immune system’s natural weakening with age.

Gerner and his fellow researchers plan to continue this research by performing their proteomic analysis on blood samples taken from greater numbers of healthy elderly people and B-CLL patients to ultimatelybe able to test when mitochondria have become predisposed for the disease.

“The pressure on those cells was simply different … and this pressure is something I would like to detect and measure in patients,” Gerner said. “That would be the ultimate aim.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Missing lipid shrinks heart and lowers exercise capacity

Researchers uncovered the essential role of PLAAT1 in maintaining heart cardiolipin, mitochondrial function and energy metabolism, linking this enzyme to exercise capacity and potential cardiovascular disease pathways.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.