Sibling study reveals mechanism for genetic disease

Genetic diseases pass from parents to children — often in surprising ways. The unpredictability of these transfers means that sometimes a disease skips whole generations, while other times it may affect only one sibling. Pairs of affected and unaffected siblings provide a unique opportunity for scientists to study the molecular mechanisms of genetic disease.

Unraveling the connection between the genetic mutation a person carries and the symptoms they have has been a decades-long focus of Yi-Wen Chen’s laboratory, part of the Center for Genetic Medicine Research at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C. Chen’s expertise is in genetic muscle disorders, which occur in 59 out of every 100,000 adults in the United States.

Muscle weakness can sometimes start early – even in the womb. Other times, as is the case with the second-most common muscle disorder, adult-onset facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, or FSHD, symptoms begin much later, in adolescence or early adulthood. Why is this, and does it hint at a way to design treatment?

To answer these questions, Chen’s laboratory teamed up with proteomics expert Jatin Burniston of the Research Institute for Sport and Exercise Sciences at Liverpool John Moores University. They studied affected and unaffected sibling pairs using proteomics experiments designed to reveal the underlying mechanisms of FSHD.

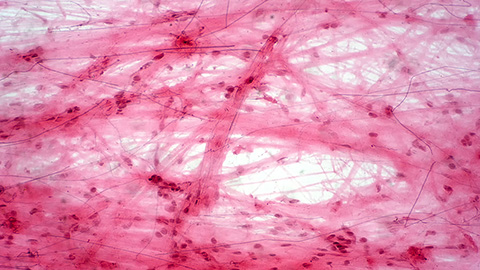

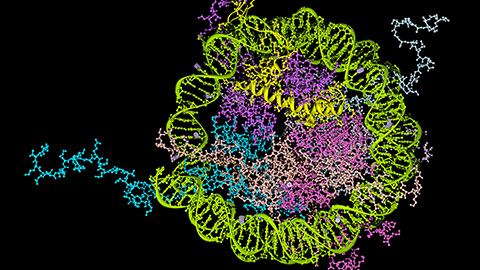

The researchers took cell cultures from each sibling and incubated them with deuterium, or “heavy water.” Then, they tracked the lifespan of each protein in the cell with mass spectrometry. The results, described in a recent article in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, implicate slower turnover of mitochondrial proteins, but more abundant mitochondrial proteins in the sibling with FSHD. Slower turnover means old proteins — which should be recycled — pile up in the mitochondria, triggering stress responses and interrupting normal cell function. The finding is a clever combination of atomic-level detail and good biological controls.

Yusuke Nishimura, a postdoctoral research associate in Burniston’s lab was a co-first author on the paper.

“Mitochondrial dysfunction and mitochondrial stress in FSDH had been identified in previous studies,” Nishimura said. However, that information alone wasn’t enough to begin designing a treatment. Because FSHD varies widely between individuals, “studying (the) underlying biological mechanisms is challenging,” he said.

Differences in protein turnover observed when comparing FSDH patients with healthy individuals may not be caused by the disease, but simply be normal variances between unrelated people. That’s where the sibling pair comes in — by simultaneously analyzing a sibling with FSHD and a sibling without the disease, Nishamura and collaborators were able to unravel the FSHD mystery.

FSHD has no treatment or cure. “Our new data on mitochondrial protein dynamics in FSHD is particularly exciting because highlighting dysfunctions in protein turnover offers a potential new therapeutic route,” Nishimura said.

Next, researchers must find a way to increase protein recycling in the mitochondria and test if the improved turnover relieves FSHD symptoms. To do so, they need to develop better mouse models of FSHD. If the evidence continues to mount, therapeutic strategies such as targeted protein degradation might be used to restore order to the mitochondria in FSHD patients.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

How sugars shape Marfan syndrome

Research from the University of Georgia shows that Marfan syndrome–associated fibrillin-1 mutations disrupt O glycosylation, revealing unexpected changes that may alter the protein's function in the extracellular matrix.

What’s in a diagnosis?

When Jessica Foglio’s son Ben was first diagnosed with cerebral palsy, the label didn’t feel right. Whole exome sequencing revealed a rare disorder called Salla disease. Now Jessica is building community and driving research for answers.

Peer through a window to the future of science

Aaron Hoskins of the University of Wisconsin–Madison and Sandra Gabelli of Merck, co-chairs of the 2026 ASBMB annual meeting, to be held March 7–10, explain how this gathering will inspire new ideas and drive progress in molecular life sciences.

Glow-based assay sheds light on disease-causing mutations

University of Michigan researchers create a way to screen protein structure changes caused by mutations that may lead to new rare disease therapeutics.

How signals shape DNA via gene regulation

A new chromatin isolation technique reveals how signaling pathways reshape DNA-bound proteins, offering insight into potential targets for precision therapies. Read more about this recent MCP paper.

A game changer in cancer kinase target profiling

A new phosphonate-tagging method improves kinase inhibitor profiling, revealing off-target effects and paving the way for safer, more precise cancer therapies tailored to individual patients. Read more about this recent MCP paper.