Under the skin and out in the world

If Elaine Fuchs had been born a century earlier, she may have been a naturalist rather than one of the most decorated cell biologists of her generation.

“I grew up in a family of scientists. But … I think what really inspired me was getting a butterfly net from my mother, who put it together and sent me out to the fields,” said Fuchs, who was raised outside of Chicago near Argonne National Laboratories, where her father worked as a geochemist. “That, and taking buckets and going out to the swamp and seeing what I could find.”

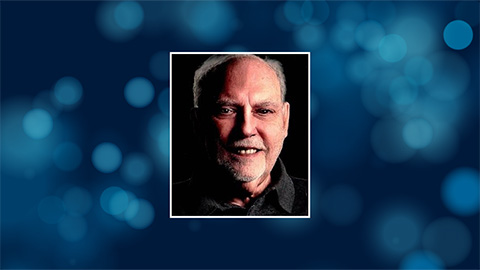

For more than four decades, Fuchs, now 69, has investigated the properties of adult stem cells that reside in skin. Much of what we know about human skin’s capacity to heal and regenerate — and, in cases of mutation, to succumb to diseases like epidermolysis bullosa — has been made possible by Fuchs’ work, from her first lab at the University of Chicago to her current position as the Rebecca C. Lancefield investigator at the Rockefeller University. Elaine Fuchs established her lab at Rockefeller University in 2002. She has been a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator since 1988.MATTHEW SEPTIMUS PHOTOGRAPHY

Elaine Fuchs established her lab at Rockefeller University in 2002. She has been a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator since 1988.MATTHEW SEPTIMUS PHOTOGRAPHY

Landing in the lab

As an undergraduate, Fuchs had no plans to become a researcher — at least not immediately. During her senior year of college, she protested the Vietnam War and had her eye on the Peace Corps. She hoped to teach chemistry in Chile, where Salvador Allende recently had become the first Marxist elected president in a Western liberal democracy.

“Growing up during the Cold War, I thought, ‘How can that happen, where people elected to have a Marxist government even though they had 100 years of democracy?’” Fuchs said.

She spent a year learning Spanish, studying Latin American history and writing papers on Chilean agrarian reform. But the Peace Corps had other plans.

“I got accepted to Uganda, and Idi Amin was in charge. He was a tyrant — he was killing his own people and just ruthless,” Fuchs said. “I thought about it, and I decided in the end to go to graduate school.”

Though the Peace Corps dream didn’t pan out, Fuchs has been an ardent traveler since her days as a graduate student at Princeton University. Her work also has taken her across oceans. In 2018, she was appointed to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, a papal think tank established in 1936 as a successor to the Accademia dei Lincei founded in 1603 under the stewardship of Galileo. In that role, and on occasion before she was appointed, Fuchs has attended scientific workshops at the Vatican to help keep the Roman Catholic Church’s highest leader apprised of the regenerative potential of stem cells derived from all areas of the body.

“They’re excited by the prospect that different tissues harbor stem cells that have in some cases, like skin, considerable regenerative capabilities,” she said. “They have a very broad base of scientists with different areas of expertise.”

For Fuchs, that area of expertise is stem cells. Elaine Fuchs has mentored more than 100 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers over her career, 65 of whom gathered together in 2015.SCOTT RUDD EVENTS

Elaine Fuchs has mentored more than 100 graduate students and postdoctoral researchers over her career, 65 of whom gathered together in 2015.SCOTT RUDD EVENTS

Building a field

When Fuchs started working on skin-derived stem cells during the field’s nascency in 1978, the cells went by a different name.

“Human epidermal keratinocytes. A very boring name,” she said. “We now, of course, know that virtually every tissue of our body has long-lived stem cells that are able to regenerate tissue, both to repair dying cells and also to repair wounds, so it’s virtually a universal property of the tissues of our body. But back then, there was very little known about it.”

At that time, Fuchs was a postdoctoral fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the lab of Howard Green, a cell biologist who pioneered skin grafting by growing human cells in culture. When Fuchs was a graduate student at Princeton working on bacterial sporulation, she had attended a guest seminar by Green about culturing cells from human skin.

“I just immediately thought, ‘That’s what I want to work on for my postdoctoral work,’” Fuchs said. “It was at the time where a few people were starting to do mammalian cell culture, but they were all on transformed cells, cancer cells, or cells where people weren’t really studying their ability to regenerate tissue.”

In Green’s lab at MIT, she met Fiona Watt, another postdoc who had just finished her Ph.D. at Oxford University.

“I always describe her as the big sister that I never had,” said Watt, now the director of the Centre for Stem Cells & Regenerative Medicine at King’s College London. “If I needed to know how to do something, she would help me. But I think pretty soon after I got to the lab, she was learning to think about her independent career and where she would go next. You could really, I suppose, in hindsight, see the scientist she was going to become.”

In Green’s lab, Watt worked to culture cells from human skin, while Fuchs attempted to clone the keratin gene. “This was really cutting-edge molecular biology, nobody else in the lab knew how to do that,” Watt said. “So there was a sense that she was really pushing the boundaries.”

After finishing her postdoc in Green’s lab, Watt returned to the U.K. to start her own lab at the Kennedy Institute of Rheumatology in London; she has continued to investigate the role of stem cells in adult tissue maintenance. This overlaps with Fuchs’ research, so they have remained close colleagues over the years. They also have built a highly collegial field of study.

“More than 10 years ago … we were at a conference in Toronto, and people from her lab invited people from my lab out for a meal,” Watt said. “And I remember saying to my lab, ‘Look, they’re just going to want to suck your brains out, know everything you’re doing, but remember you can probably drink more than they can.’ And that evening, I wasn’t there. I don’t think Elaine was either. But it was transformative for the field. Because the scientists in each of our labs at the time were some of the best we’ve ever trained. They got on really well with one another, and instead of feeling that you’re either in the Fuchs lab or the Watt lab, it was, ‘This is the field that we care about. And we have to help one another.’”

By their lab’s records, Fuchs and Watt collectively have trained more than 200 Ph.D. students and postdocs in the decades since they left Green’s lab at MIT.

“We may have started out with that with that big sister–little sister dynamic,” Watts said. “But now we’ve founded these massive dynasties. And they all have these wonderful networks of relationships amongst each other.”

Female bonding

Following in the footsteps of their postdoctoral mentor Elaine Fuchs, Shruti Naik (left) and Julie Segre (right) both received the Damon Runyon Postdoctoral Fellowship Award.DAMON RUNYON CANCER RESEARCH FOUNDATIONFuchs’ knack for building supportive networks was especially useful at the University of Chicago, where she was the first woman hired at the department of biochemistry.

Following in the footsteps of their postdoctoral mentor Elaine Fuchs, Shruti Naik (left) and Julie Segre (right) both received the Damon Runyon Postdoctoral Fellowship Award.DAMON RUNYON CANCER RESEARCH FOUNDATIONFuchs’ knack for building supportive networks was especially useful at the University of Chicago, where she was the first woman hired at the department of biochemistry.

When she was setting up her laboratory, a technician from another lab asked her if she was Dr. Fuchs’ new technician. She replied, “I am Dr. Fuchs.”

Such interactions weren’t new to Fuchs; in her undergraduate physics class at the University of Illinois, she was one of three women in a lecture hall of 200.

“I would see, in retrospect, a tremendous amount of discrimination, but I didn’t recognize it as that,” she said. “I just took it as the need to do better. My adviser at Princeton didn’t think women belonged in science, and I just thought, ‘Well, that means I need to work that much harder.’

“It was a little annoying (receiving) really derogatory comments made by some of my colleagues if they would get irritated over a remark I would make. On the other hand, you kind of take that as water off a duck’s back.”

By Fuchs’ account, a turning point at the University of Chicago came when she and her colleagues Janet Rowley and Susan Lindquist took advantage of a departmental reorganization to join the department of molecular genetics and cell biology.

In 2016, Elaine Fuchs received an honorary doctorate from Harvard University.COURTESY OF ELAINE FUCHS“Each department had their token woman or two, and, when we organized and were allowed to join one department, we all decided to join the same department,” Fuchs said. “And it was really only then that I think it really did start to feel different, because I did have colleagues who thought the same way and weren’t derogatory.”

In 2016, Elaine Fuchs received an honorary doctorate from Harvard University.COURTESY OF ELAINE FUCHS“Each department had their token woman or two, and, when we organized and were allowed to join one department, we all decided to join the same department,” Fuchs said. “And it was really only then that I think it really did start to feel different, because I did have colleagues who thought the same way and weren’t derogatory.”

Within that new environment, she was able to stake out her support for equality at the university.

“It’s important to pick the battles that you have, and so I picked them with issues that were grossly unfair in terms of say, salary, or now, in terms of the importance of just having representation at scientific meetings.”

Fuchs’ camaraderie with women scientists cuts across fields. For Mina Bissell, former head of life sciences at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, a galvanizing moment in their friendship came in the early 1990s at a large scientific meeting in Chicago.

At that meeting, Fuchs took the podium to present research findings that expressing a mutant keratin in mice could make them display a skin-blistering phenotype identical to epidermolysis bullosa simplex, or EBS, in humans.

According to Bissell, who had met Fuchs a few years earlier when she had visited LBNL, Fuchs soon was assailed by a senior keratin researcher from Australia.

“I have never seen anything so arrogant,” Bissell said. “This man was so biting: ‘And you mean that this mouse is replicating human disease? That’s nonsense.’ I mean, he just went on and on.

“I got so mad that I stood up. I said, ‘Excuse me, what’s your problem? She very nicely has described her data; she’s made the mice imitate human disease. And you don’t believe it? Go to your own lab and do it. For crying out loud, do it yourself. What are you doing being so mean?’”

“I got so mad that I stood up. I said, ‘Excuse me, what’s your problem? She very nicely has described her data; she’s made the mice imitate human disease. And you don’t believe it? Go to your own lab and do it. For crying out loud, do it yourself. What are you doing being so mean?’”

By Fuchs’ account, Bissell’s defense was the catalyst for the chair of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania to corroborate Fuchs’ diagnosis of EBS. Eight months later, her work displaying mutant keratin overexpression as a cause of EBS in mice appeared in the journal Cell.

Leadership

Though Fuchs has been an active leader in the scientific community, research and mentorship have remained priorities for most of her career.

“I’ve never chaired a department. I’ve never been a dean, I’ve never been the president of the university. I’ve never wanted to be any of those,” she said. “I really take the professor’s side very seriously. It’s not just the research that we do, it’s also important for me to mentor students as part of my professorship. So that’s where I funneled the bulk of my energy over my career.”

Julie Segre, now a senior investigator at the National Human Genome Research Institute who examines the composition of the human skin microbiome and tracks hospital-associated bacterial pathogens, joined Fuchs’ lab at the University of Chicago as a postdoctoral fellow in 1996.

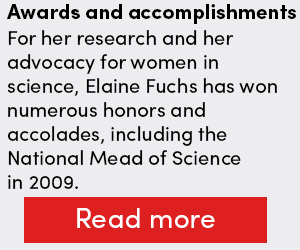

Elaine Fuchs met President Bill Clinton when both of them spoke at the University of Chicago’s undergraduate convocation ceremony in 1999.COURTESY OF ELAINE FUCHSSegre had been involved with the Human Genome Project at MIT while working on her Ph.D. and was interested in combining her genomic and technological skill set with biological questions regarding proliferation and differentiation in organ systems. In the Fuchs lab, she was able to explore those questions in a subgroup devoted to cell differentiation.

Elaine Fuchs met President Bill Clinton when both of them spoke at the University of Chicago’s undergraduate convocation ceremony in 1999.COURTESY OF ELAINE FUCHSSegre had been involved with the Human Genome Project at MIT while working on her Ph.D. and was interested in combining her genomic and technological skill set with biological questions regarding proliferation and differentiation in organ systems. In the Fuchs lab, she was able to explore those questions in a subgroup devoted to cell differentiation.

“Elaine is fiercely involved in every scientific project in her lab,” Segre said. “You had time to develop a project, but then at a certain point, the project would capture Elaine’s imagination. She would decide that you were close to finishing, and then you would kind of go into overdrive … she was pretty amazing at never having anything sit.”

After four years in Fuchs’ lab, Segre took a position at the NHGRI of the National Institutes of Health, where she was promoted to senior investigator in 2007.

“Elaine has continued to be engaged in my scientific development and scientific life, and I still consider her the mentor that I would go to for both scientific advice and (scientific) conversation,” Segre said. “It’s always nice when people say, ‘Oh, now we’re just colleagues.’ And I’m like, I would never give up being one of Elaine’s mentees, because she has so much to give that I still do want. I have a lot of colleagues, but I only have one postdoc adviser.”

Traveling partners

Fuchs with her friend Mina Bissell and her husband, David Hansen.courtesy of elaine fuchsDuring her semester breaks as a graduate student at Princeton, Fuchs made the most of the Spanish she’d honed for the Peace Corps, traveling to Guatemala, Mexico, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru. Subsequent trips found her visiting Greece, Turkey, Egypt and Nepal.

Fuchs with her friend Mina Bissell and her husband, David Hansen.courtesy of elaine fuchsDuring her semester breaks as a graduate student at Princeton, Fuchs made the most of the Spanish she’d honed for the Peace Corps, traveling to Guatemala, Mexico, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru. Subsequent trips found her visiting Greece, Turkey, Egypt and Nepal.

A few years later at the University of Chicago, her colleague and close friend Susan Lindquist introduced her to David Hansen, a history buff and fellow academic who had done a stint with the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone. The two hit it off over their mutual interest in traveling and soon visited South Africa together.

“We just started traveling places that we hadn’t been between the two of us,” Fuchs said. “Our honeymoon was Zimbabwe and Botswana — Victoria Falls instead of Niagara Falls.”

In recent years, Fuchs and Hansen have been to Indonesia, Laos, Tanzania and, on several occasions, Myanmar.

All that travel takes a toll; earlier this summer, Fuchs had hip replacement surgery, a procedure she took in stride.

“These days, it’s basically like going down and getting an oil change for your car. It’s fairly routine,” she said of the surgery. “(But), if you use it, it is going to wear down, and I tend to be active.” Outside of the lab, Elaine Fuchs loves documenting her travels through photography.

Outside of the lab, Elaine Fuchs loves documenting her travels through photography.

See more of her photos below.ELAINE FUCHS

Fuchs’ love of travel led to one of her favorite hobbies, photography.

“My favorite are pictures of people,” she said. “But (recently) I’ve gotten really fascinated with leopards, and also with birds.”

She and Hansen are planning a trip to the Galápagos Islands this winter, where she is excited to photograph the panoply of birds that call the archipelago home.

“In another life, I think I would want to be out with National Geographic,” she said.

In this life, her professional evolution has stuck to science.

“I was a chemistry major at the University of Illinois, in Champaign–Urbana, and I was good at it. But I knew it wasn’t my calling. And then at Princeton, I was doing biochemistry, seeing if I could find something more biomedically oriented. And that really wasn’t it either. And then it was that spark of hearing Howard Green speak. And I knew then that that’s really what I wanted to do. So I think it’s a progressive maturation, honing our scientific star that’s inside of us.”

Awards & accomplishments

Throughout her career, Elaine Fuchs has been an advocate for women in science; for this, in addition to her groundbreaking research, she received a L’Oréal–UNESCO Award for Women in Science in 2010. Her accolades also include a National Medal of Science in 2008 and, this year, the American Association for Cancer Research’s Clowes Memorial Award.

Fuchs was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1994, the National Academy of Sciences in 1996, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2008. She has served as president of the American Society for Cell Biology, the International Society for Stem Cell Research and the Harvey Society; has contributed to numerous scientific advisory boards and review panels; and has served on the board of governors for the New York Academy of Sciences and the board of directors for the Damon Runyon Cancer Foundation.

Elaine Fuchs received the National Medal of Science from President Barack Obama on Oct. 8, 2009.ANDY SCHAEFFER/NSF

Elaine Fuchs received the National Medal of Science from President Barack Obama on Oct. 8, 2009.ANDY SCHAEFFER/NSF

Additonal images

Subspecies of the malachite kingfisher can be found in many sub-Saharan African countries.Elaine Fuchs

Subspecies of the malachite kingfisher can be found in many sub-Saharan African countries.Elaine Fuchs

Little bee-eaters hunt their eponymous prey from low perches a few feet from the ground.Elaine Fuchs

Little bee-eaters hunt their eponymous prey from low perches a few feet from the ground.Elaine Fuchs

Giraffes can run up to 35 mph over short distances.Elaine Fuchs

Giraffes can run up to 35 mph over short distances.Elaine Fuchs

More than one million wildebeest migrate across East Africa each year.Elaine Fuchs

More than one million wildebeest migrate across East Africa each year.Elaine Fuchs

Lions can sleep up to 20 hours a day.Elaine Fuchs

Lions can sleep up to 20 hours a day.Elaine Fuchs

Elaine Fuchs

Elaine Fuchs

Elaine Fuchs

Elaine Fuchs

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

In memoriam: Walter A. Shaw

He is the namesake for the Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research and founded Avanti Polar Lipids.

Dorn named assistant professor

She will open her lab at the University of Vermont in fall 2026, and her research will focus on catalysis, synthetic methodology and medicinal chemistry.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Kiessling wins glycobiology award

She was honored by the Society for Glycobiology for her work on protein–glycan interactions.

2026 ASBMB election results

Meet the new Council members and Nominating Committee member.