A macrocyclic lipid and the enzyme that makes it

There’s a lot to adapt to when home is a hydrothermal vent deep in the ocean. For starters, the water can be hot enough to melt a lipid bilayer.

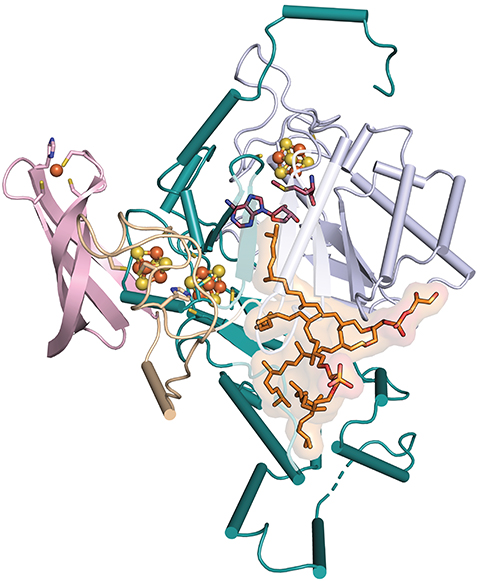

One of many adaptations that extremophilic microorganisms called archaea make to survive their superheated, high-pressure and frequently acidic environments is remodeling their cellular membranes. Instead of two layers of lipids, archaea can link two glycerolipids by their tails to form a large, cyclic lipid called GDGT with head groups on both the intracellular and extracellular surfaces.

“GDGT was discovered decades ago, but no one knew what enzyme made it,” said Cody Lloyd, a graduate student at Pennsylvania State University.

Biosynthetic pathways that researchers had already worked out accounted for the lipid’s precursors but left out a single puzzling step. Somehow, the archaea must catalyze an end-to-end joining of two unreactive carbon chains. The reaction seemed to require radical chemistry, which frequently uses oxygen — but the organism in question is an obligate anaerobe.

Lloyd came across the enzyme by accident. With Amie Boal and colleagues in Squire Booker’s and William Metcalf’s labs, he reported in Nature this year its identity, its reaction mechanism and that it links the two carbons using a whole new type of radical chemistry.

While studying an enzyme believed to be a methyltransferase, Lloyd struggled to observe its reported activity. “When we solved the structure, we realized that the active site was not consistent with the proposed reaction at all,” he said.

Instead, they observed two lipids bound to the protein. Reading up on archaeal lipids, they learned about the mysterious cyclic lipid.

The researchers crystallized the protein and got it working in a test tube using a synthesized substrate. Using mass spectrometry, they captured a reaction intermediate that illuminated the enzyme’s mechanism. It abstracts a hydrogen atom from the last carbon of two saturated lipid molecules and uses an iron–sulfur cluster to stabilize one radical intermediate until the second is ready to react.

No one had ever observed an enzyme using an iron–sulfur cluster to tame a high-energy radical; the cofactor is usually involved in redox reactions. The reaction itself is also exciting for biochemists and synthetic chemists because sp3-hybridized carbons are notoriously nonreactive. Catalyzing a new bond between them is difficult in the lab and never had been observed before in nature.

“This project was thrilling,” said Squire Booker, Lloyd’s research adviser — and it stayed thrilling even when a Stanford group identified a GDGT-synthesizing ortholog a few months before the paper came out. “However, Cody’s work, besides providing the structure of the enzyme, settled a major conundrum in the field involving the nature of the substrate, and demonstrated for the first time one strategy that nature uses to link completely unactivated sp3-hybridized carbons.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

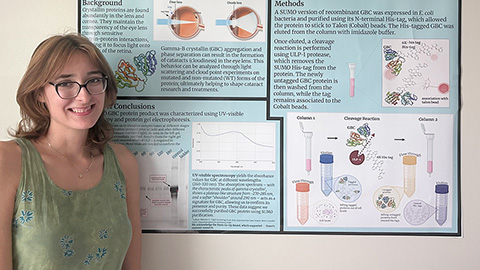

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.