State laws change the landscape for LGBTQIA+ scientists

Passage of the Parental Rights in Education Act in March 2022 pitched the state of Florida into the media spotlight. Widely dubbed “Don’t Say Gay,” the law banned teaching about sexual orientation and gender identity in grades K-3. The measure also mandated age or developmentally appropriate teaching on these topics for older students "in accordance with state standards," leaving murky the question of how Florida’s schools would treat LGBTQIA+ parents and youth.

Tracking this political news was Sarah L. Eddy, a tenured associate professor in the biological sciences department at Florida International University in Miami. Eddy was not a parent but had cause for concern as a scholar who was directing three research projects on equity and diversity in education, with a focus on LGBTQIA+ people.

“Seeing that bill come up was one of the warning signs,” said Eddy, who is nonbinary and uses the pronouns they and their. “That made me realize that, if I wanted to … not feel trapped, then I needed to look for jobs.”

Eddy’s FIU colleagues had backed their research interests, but Eddy knew the department’s protection had its limits. “My chair and everyone has been really supportive, and they have no power to stop repercussions if they come down from the state,” they said when interviewed in April. “If the laws of the state change, they have to enforce them: That threat makes me feel really exposed, even if they say they have my back.”

Eddy began applying to other positions around the country. That search led them to a prospective job at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities, where the process put them at ease. “One of the things I noticed in the interview is that people used my pronouns naturally and that felt really good,” Eddy said.

Like migrating birds that follow landmarks and terrain, academic researchers like Eddy take cues from their environment as they chart a career. Today, the factors steering job moves may extend beyond the allure of a hiring institution, ties to family and friends, or the charms of college towns. For LGBTQIA+ job seekers, the political climate of a state increasingly affects its draw as a career destination.

When Emiliano Brini, a physical and computational chemist, set out to find his first tenure-track post in 2021, his criteria included a culture friendly to LGBTQIA+ people. As an Italian resident of the United States, he was looking to put down roots in his adopted country following stints as a postdoctoral fellow and research scientist at Stony Brook University in New York. Now, location mattered.

“I always say you can find good science and good colleagues, but you need to live in this place,” Brini said, referring to any U.S. state he would consider. “When I was looking for a job, I had very strict geographic restrictions.”

Brini limited his search to the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic U.S., along with California and Washington state. As a gay man, he was unwilling to deal with a hostile social environment on top of the rigors of starting a lab. He took a job as assistant professor at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

“Being in tenure track is hard enough,” said Brini, whose research uses physics-based simulations to study biologically relevant projects related to drug design. “I don’t need to worry about the political climate.”

Shifts in the political landscape

T.J. Ronningen, chair of Out to Innovate — a professional network of LGBTQIA+ students and professionals in science, technology, engineering and mathematics — has heard similar concerns from his members about new legislation in a growing number of states.

Texas Gov. Greg Abbott drew national attention in February 2022 when he ordered child abuse investigations of any parents whose transgender children were receiving gender-affirming care. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis moved this spring to expand the “Don’t Say Gay” law to grades K–12.

As the year began, governors in Utah and South Dakota on Jan. 28 and Feb. 13, respectively, signed laws banning gender-affirming medical care for transgender patients under the age of 18. On March 16, Florida’s board of medicine, which is appointed by the governor, banned the use of all puberty blockers, hormone therapies and gender-affirming surgeries for people under 18, regardless of parental approval for such care. At least 16 other states have now banned gender-affirming health care, largely in the South and Midwest.

“The climate and laws are shaping people’s decisions about where they would be willing to work,” Ronningen said. “We are hearing from members that they are concerned about these trends.”

Ronningen views these recent measures as a throwback to the late 1990s and early 2000s when legislation hostile to his community also helped shape where people lived in the United States.

That era saw the LGBTQIA+ community both moving forward and sliding back in legal rights. In a 1996 decision, Romer v. Evans, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down an amendment to Colorado's constitution that denied to gays and lesbians protection against discrimination. Yet, later that year, President Bill Clinton signed into law the Defense of Marriage Act, which defined marriage as between a man and a woman, and let states refuse to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states.

With Lawrence v. Texas in 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down laws against adult nonprocreative sex, known as sodomy laws, as unconstitutional. In 2004, Massachusetts was the first state to legalize same-sex marriage, followed, over the next six years, by New Hampshire, Vermont, Connecticut, Iowa and Washington, D.C. However, LGBTQIA+ rights regressed in 2008, when Proposition 8 outlawed same-sex marriage in California.

Marriage equality became the law of the land nationwide after the Supreme Court’s Obergefell v. Hodges decision in 2015, but Ronningen saw the impact of the state legislation that preceded that case.

“A patchwork of laws across the country creates a disinclination to move to certain areas,” he said, noting the nation’s uneven legal framework then and now.

When the résumé meets the region

Like many early-career researchers, John Schmidt occasionally checks job listings in his field. Schmidt has worked as a teaching professor of biology and biochemistry at Villanova University for the past eight years. He and his husband enjoy their life together in nearby Philadelphia.

However, it would take more than better pay or a better-equipped lab for him to leave his position. For one thing, his husband does occasional drag performances. In early March, drag shows were banned outright in Tennessee, though the law faces legal challenges, and legislatures in at least nine states from Arizona to Texas have sought to restrict the shows.

“I see lots of opportunities in locations where I would be a good candidate, but I automatically rule them out because of the political climate,” Schmidt said. “Even if the university is great, I don’t want to live in an unwelcoming community.”

Schmidt’s outlook matches that of many young professionals in the business world, according to Jane Barry–Moran, managing director of research and programming with Out Leadership, which seeks to develop LGBTQIA+ and ally leaders at businesses worldwide. Her group commissioned a 2019 study that examined relocation of LGBTQIA+ young professionals.

“What we found is that 36% of young LGBTQ+ talent would be willing to move to a more inclusive place; 31% would be willing to take a pay cut to make that relocation possible,” Barry–Moran said. What’s more, 24% of the LGBTQIA+ workers surveyed had already moved to a more hospitable city.

A separate study by Abbie Goldberg, co-sponsored by Clark University and the Williams Institute on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Law and Public Policy at the University of California, Los Angeles, explored the impact of Florida’s “Don’t Say Gay” law on LGBTQIA+ parents in the state.

Released in January 2023, Goldberg’s survey found that 88% of parents surveyed in the law’s aftermath were very or somewhat worried about its impact on their children and families. Some of their children had suffered harassment and bullying at school; some children were afraid to mentioning their parents’ or their own gender identities, and had fears about living in Florida. Looking ahead, 56% of the parents surveyed were weighing a move out of state, and 16.5% had taken steps to do so, such as seeking jobs elsewhere.

Young adults in the science pipeline who are planning parenthood could make political climate part of their calculus for postdoctoral plans. Inayah Entzminger is a nonbinary bisexual who uses the pronoun they and is working toward a biochemistry doctorate at Hunter College in New York. When they contemplate their future, they picture an accepting place to start a family.

“When I’m searching for a career, I’m going to be looking to raise children,” Entzminger said. “The U.S. has lots of science hubs, but I will be choosing an area that does not have anti-trans laws, that doesn’t have ‘don’t say gay’ laws.”

To help people like Entzminger and companies make informed decisions, Out Leadership teamed up with the Williams Institute to survey the business climate for LGBTQIA+ professionals in the 50 U.S. states. The June 2022 survey attempts to gauge how friendly to LGBTQIA+ people states are, based on three sets of criteria: personal protective and nondiscrimination laws, youth and family support, and work-related discrimination and protections.

The worst ratings went to South Carolina, joined in ascending order by Oklahoma, Tennessee, South Dakota and Arkansas. Alabama ranked 43 out of 50, Texas ranked 42, and Florida ranked 31.

Northeastern states topped the ratings list, with the No. 1 slot going to New York, where Brini, the Italian chemist who did his postdoc at Stony Brook University, settled in 2021. He enjoys the large, active LGBTQIA+ community in what he calls his “very welcoming” adopted hometown of Rochester. “My partner and I live in a neighborhood where most houses fly rainbow flags and have BLM (Black Lives Matter) signs,” Brini wrote in an email.

That kind of community appeals to Entzminger as a graduate student who hopes to conduct research while raising a family. “It’s all about being around people who are there for you,” they said. “I could not be a scientist in a place where I feel unsafe.”

For Aflah Hanafiah, location may be even more fraught. A sixth-year graduate student in biochemistry at Pennsylvania State University, Hanafiah is passionate about the protein regulators of cytokinesis, which are widespread proteins that modulate histones, helping to shape chromosomes in a wide array of living things.

Hanafiah brings a broad range of identities to her work in science. “I am trans, I am a woman, a noncitizen of the U.S.A. and a nonwhite student,” she said. “There’s a lot of challenges that come with who you are.”

Born and raised in Malaysia, Hanafiah came to the United States nearly a decade ago, drawn by her adoptive country’s strong science research and relative freedom. “One of the reasons I wanted to pursue education and other opportunities outside my home country is the very hostile climate in Malaysia” toward trans people, she said.

Yet, as she looks beyond graduate school, Hanafiah knows she will have to choose carefully where to launch her career. Her boyfriend has proposed Texas as a destination, spurring what she calls “very, very difficult” conversations about a safe place for her to settle.

Texas, as noted earlier, has some anti-trans policies. What’s more, Equality Texas, a LGBTQIA+ rights group, reported 18 murders of transgender people in 2020 in Texas, second only to Florida, with 20 such murders, according to the group.

Unsettling choices: To leave or to stay

Sonia Flores, chair of the Maximizing Access Committee for the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, said she sees legislation now targeting the LGBTQIA+ community, combined with anti-abortion laws, having an impact both in the states in question and in neighboring ones.

“This is resulting in a brain drain from a lot of these states,” Flores said.

As the vice chair for diversity and justice in the department of medicine and associate program director for diversity of the pulmonary fellowship at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Flores is witnessing the effects firsthand.

“We’re getting an influx of people seeking jobs here,” she said. “They’re saying, ‘I don’t want to live in Texas or another state like that.’”

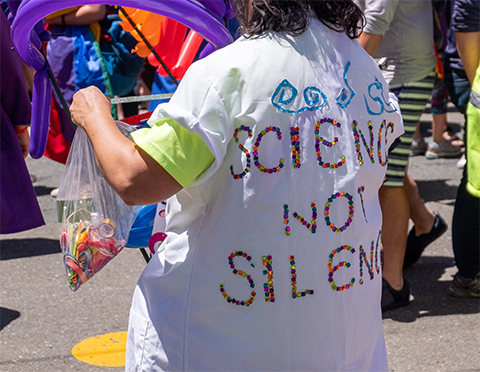

Flores said she believes the anti-LGBTQIA+ measures flowing out of state houses are related to “anti-science sentiment” that appears to lead lawmakers toward “creating policies out of thin air without any basis in fact or evidence.”

Last year, Alabama passed one of the most far-reaching anti-LGBTQIA+ measures in the country, according to the Human Rights Campaign, an LGBTQIA+ advocacy group. The law, signed by Gov. Kay Ivey in June 2022, makes it a crime to provide gender-affirming medical care to transgender youth and bars transgender students from using a bathroom matching their gender identity. It also limits what teachers can tell their students about gender identity and sexual orientation. Further, it requires school leaders to inform a student’s parents if the student identifies as LGBTQIA+.

In January, Constanza Cortes left her job as an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham for a similar post at the University of Southern California.

“I can tell you when some of those bills were passed, that’s when I went on the job market,” Cortes said. “I am not part of this (LGBTQIA+) community, but many of my friends are.”

For Cortes and other early-career faculty, it was not simply a question of their own comfort in a fraught political climate. “I was asking, what would this mean for my career and for the careers of my trainees, the people in my lab?” Cortes said.

She and her Alabama colleagues soon got an answer when they faced obstacles in recruiting new employees to the campus. “I can say that many of my colleagues and I were struggling to fill positions,” Cortes said. “This was at every level.”

As to her new home state, Cortes waxed enthusiastic in an email sent in early April. A region known to be welcoming to LGBTQIA+ people also seems to be a better environment for her as a Latina immigrant.

“The culture of inclusivity here in Southern California is quite palpable and can be seen, heard and experienced just by stepping outside,” Cortes wrote. “It is a great fit for me professionally and personally, as I do not feel I have to limit who I am or the way I express myself here.”

Down on the Gulf Coast, Andrew Hollenbach is a professor of genetics and co-director of the Basic Sciences Curriculum for the School of Medicine at Louisiana State University. His adopted home state ranks No. 45 on the Out Leadership business climate survey.

Yet, as an out gay professional, Hollenbach has found a supportive community in New Orleans. “I’m in a deep blue bubble in a deep red state,” Hollenbach said, alluding to his state’s partisan divide. “At LSU, I’ve had 4,000% support from the administration.”

He and his colleagues teach their institution’s medical students to serve an increasingly diverse patient population, including the LGBTQIA+ community.

“Everyone at LSU is so dedicated to giving students the education they need to treat whoever walks into the clinic,” Hollenbach said, “regardless of their background or what underrepresented population they may be part of.”

Hollenbach, a native Pennsylvanian, now is rooted in Louisiana. He cannot imagine leaving, even if shifting political winds there bring anti-LGBTQIA+ measures — unless he had to care for his elderly mother back in his home state.

“I am too vested in fighting this,” he said of the movement to roll back legal rights. “New Orleans is my home; I would retire before I would relocate.”

Making an institutional impact

Bioscientists who work in industry, and the companies they serve, have their own choices as they confront anti-LGBTQIA+ state laws. Out to Innovate’s Ronningen believes corporate policies also can have an impact on morale for LGBTQIA+ employees, no matter what political environment lies outside the office suites.

“In a climate where the company may not feel free to oppose legislation, it can still choose to create an internal climate that makes (clear) their support for affected employees,” Ronningen said.

For companies and for academic institutions, he said, internal measures can mitigate political climate change. “Private companies and universities still have a lot of flexibility, because they can carve out their own policies.”

Of 10 biotech companies contacted for this story, none agreed to take questions about their policies in support of LGBTQIA+ employees or about their public stands on legislation that impacts these staff members. However, two companies, Genentech and Eli Lilly and Company, each sent a statement detailing relevant programs and policies.

“Genentech has long supported LGBTQIA+ rights within and beyond our walls — from being one of the first companies to extend benefits coverage to employees’ same-sex domestic partners in 1994 to last year becoming a corporate sponsor of Victory Fund and Victory Institute,” the Genentech statement reads in part. “We strongly oppose discrimination of any kind against LGBTQIA+ people or any obstruction of their access to healthcare. We have also signed on to the Human Rights Campaign’s Business Statement Against Anti-LGBTQ State Legislation.”

The Victory Fund raises money for LGBTQIA+ political candidates in the United States. An allied group, the Victory Institute, provides leadership development, training and meetings to boost the number, diversity and success of openly LGBTQIA+ elected and appointed officials.

Signed by over 300 companies, the HRC Business Statement reads in part, “We are deeply concerned by the bills being introduced in state houses across the country that single out LGBTQ individuals — many specifically targeting transgender youth — for exclusion or differential treatment. … These bills would harm our team members and their families, stripping them of opportunities and making them feel unwelcome and at risk in their own communities.”

Over at Eli Lilly, the company supports a reverse mentoring program by LGBTQIA+ employees for Lilly managers. Each manager meets at least four times with two mentors and learns about their life experience.

“One of the measures of success of this program is that the program continues to thrive after more than 10 years — Lilly employees continue to want to serve as mentors or participate as mentees,” a Lilly spokesperson wrote in an email. “In fact, there is already a wait list of people who want to be mentored in 2023.”

She noted that many members of Lilly’s senior leadership team, including Dave Ricks, the company’s chair and CEO, have taken part in the learning program. In 2022, 25 Lilly managers were mentees.

As for academia, willingness to speak up on legislative issues seems to depend on location. Two senior faculty members at state universities in the South said they share concerns about recent legislation but asked not to be named. One noted that not only LGBTQIA+ issues but diversity, equity and inclusion efforts on campus and faculty tenure have been targeted by lawmakers in their state. The other said senior scientists at academic institutions in five states in the country’s South and heartland have told him that job seekers are reluctant to consider their universities.

“There are some states that folks aren’t even willing to look into moving to,” he said, noting those states include his own.

Ronningen would like to hear academic leaders and scientific groups speak out.

“There’s a concern that the voices of scientists and medical providers are being ignored,” he said. “If institutions — departments or scientific societies — can use their power and bring that forward in (legislative) hearings, there is research to support better answers than are being offered in this anti-LGBTQ legislation.”

How the society takes a stand

Ann Stock, president of the ASBMB, said the society is committed to diversity, including LGBTQIA+ scientists. “We are very much aligned with supporting a diverse group of scientists,” Stock said, citing the ASBMB’s official stand on diversity. “Inclusivity and opportunity for all is really important to us.”

The ASBMB’s public affairs team avoids weighing in on state laws, but the organization’s national stands sometimes have state impact, according to Raechel McKinley, an ASBMB science policy manager.

Among recent policy stands with implications for anti-LGBTQIA+ measures, McKinley said her team noticed that the National Science Foundation failed to include the LGBTQIA+ community in its biennial reports on diversity in science, technology, engineering and medicine. The ASBMB has urged the NSF to include this category in the next report, and the agency recently stated that it will include experimental questions pertaining to biological sex at birth, sexual orientation and gender identity in the next annual NSF Survey of Earned Doctorates.

A similar report by the National Institutes of Health included LGBTQIA+ people. “When they did collect data on LGBTQ+ people,” McKinley said, “they found that they were likely to suffer sexual harassment, but we wouldn’t be able to collect that data if they weren’t included.”

The ASBMB also has called for more inclusive enforcement of Title IX, the law barring gender discrimination in U.S. education, including at federally funded universities. The society sent a letter urging this change on Sept. 12 to the Office for Civil Rights at the U.S. Department of Education.

“We’re advocating for new rule making that will expand the coverage of Title 9 to the LGBTQ+ community,” McKinley said. “This is another way that we’re indirectly fighting what’s happening at the state level.”

As chair of the Maximizing Access Committee, Flores is among the ASBMB leaders spearheading diversity efforts. She urged non-LGBTQIA+ researchers to make their voices heard.

“Even though we are trained to keep our heads down, go to the lab and do our work, the social context affects us,” she said. “As scientists, we should be vocal.”

A law affecting one segment of the population may fuel legislative moves on other issues of concern to all who work in the sciences, she suggested.

“You can start with ‘Don’t Say Gay,’ and it can move very quickly,” Flores said. “It can start small and move up the chain and have a very significant impact on the research that you do, and that’s why we should all care.”

Flores speaks from experience. A few years ago, she was offered the post of chief diversity officer at a Florida university. Gov. Ron DeSantis, who last year championed the “Don’t Say Gay” measure for Florida public schools, early this year moved to defund diversity, equity and inclusion programs in universities across the state.

“If I had gone there, I would be without a job,” Flores said.

Scientific, economic fallout projected

Historically, biomedical research in the United States, both corporate and academic, has clustered in the Northeast Corridor and along the West Coast. Funding reports from the NIH illustrate the geographic science gap. Some observers suggest that anti-LGBTQIA+ measures, along with anti-abortion laws, could heighten those disparities.

“There’s not a uniform distribution of scientific research, as evidenced by NIH funding per state and pharmaceutical and biotech investment per state,” Stock said. “I’m afraid this may exacerbate that situation.”

Stock likened the potential impact of anti-LGBTQIA+ laws to that of anti-abortion legislation that followed the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision of June 2022 in Dobbs v. Jackson overturning abortion rights.

“It seems that there are strong parallels with the anti-abortion legislation that is likely influencing the geographic choices made by postdocs and young academics,” Stock said.

The research community’s reaction to both kinds of laws could intensify regional divides, she suggested.

“It is likely that employees will vote with their feet, and while certainly understandable, this exacerbates the problem, removing voices of opposition to the legislation and reducing the number of people in the community who are supportive of LGBTQ and women’s rights over their own bodies.”

Having spent three years in Alabama, Cortes also worries that the uneven distribution of research grants nationwide will get worse amid the growing political divide. “That’s going to create even more disparities,” she said. “My concern is that legislation like this (Alabama’s anti-LGBTQIA+ law) will keep highly successful researchers from applying.”

Flores underscored the economic contribution of science hubs to surrounding communities — and the potential economic loss if large numbers of scientists relocate away from these geographic areas.

“When you look at a university or research center, they’re injecting a lot of money into the local economy,” she said. “That’s a huge economic impact that hasn’t been considered when passing these draconian laws.”

For instance, Sarah Eddy decided to leave Florida. At summer’s end, they will begin a new phase in their career as a tenured associate professor in the biology teaching and learning department at the University of Minnesota.

When Eddy settles into their new professional home this fall, they will bring several research grants, totaling some $1 million, to Minneapolis–St. Paul. These grants, arguably, represent research staff, salaries and concomitant consumer spending that otherwise would have contributed to the municipal and state coffers of Miami and Florida, respectively.

Before deciding on the move to the Twin Cities, Eddy already knew from research and conversations with former residents that they would be trading a hostile political climate in Florida for a friendlier one in the Upper Midwest. A new development in March confirmed Eddy’s resolve to relocate northward.

“After I accepted the job, Minnesota declared itself a sanctuary state for those seeking gender-affirming care,” they said. “That was a huge affirmation that I made a good choice.”

Back in Rochester, Brini is charting his next research projects on the thermodynamic properties of protein–protein interactions, the solvation of organic druglike molecules and more. He seeks to set the stage for development of new medications against viruses, bacterial infections and even cancer.

“These are tools that are going to be used to design new drugs and new classes of drugs,” Brini said. “I think my research is important for the future.”

Brini’s own future, however, and that of other scientists like him, likely will unfold in places with LGBTQIA+ friendly laws, policy and cultural climates. If he hadn’t clinched his tenure-track position in New York or one of the eight other U.S. states he considered, Brini said, he would have taken his talents to London or elsewhere in Europe.

Raechel McKinley, science policy manager with the ASBMB’s public affairs team, contributed her technical expertise to this story.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Calling all biochemistry and molecular biology educators! Share your teaching experiences and insights in ASBMB Today’s essay series. Submit your essay or pitch by Jan. 15, 2026.

Defining a ‘crucial gatekeeper’ of lipid metabolism

George Carman receives the Herbert Tabor Research Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building the blueprint to block HIV

Wesley Sundquist will present his work on the HIV capsid and revolutionary drug, Lenacapavir, at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, in Maryland.

Upcoming opportunities

Present your research alongside other outstanding scientists. The #ASBMB26 late-breaking abstract deadline is Jan. 15.

Designing life’s building blocks with AI

Tanja Kortemme, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, will discuss her research using computational biology to engineer proteins at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Upcoming opportunities

#ASBMB26 late-breaking abstract submission opens on December 8. Register by Jan. 15 to get the early rate on our Annual Meeting.