Bumpus leads with science

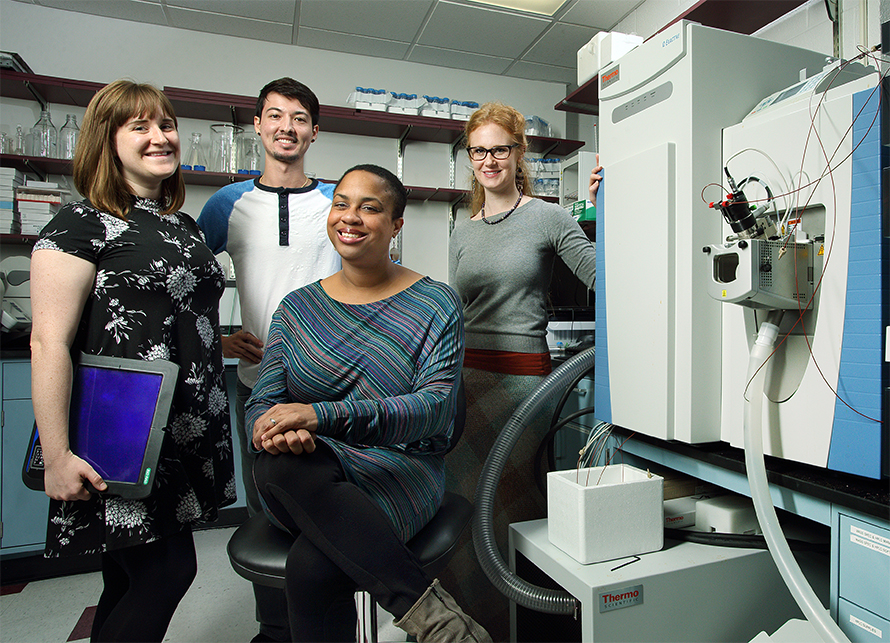

When Namandjé Bumpus was at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, as associate dean of basic research and later as head of the pharmacology department, her lab worked on how liver enzymes called cytochrome P450s metabolize drugs. Focusing on drugs used to treat HIV and hepatitis C, Bumpus used mass spectrometry to identify drug metabolites in patient samples, enzymology to determine how they are formed and pharmacogenetics to understand why patients vary in their response to the same molecule.

After more than a decade in academia, Bumpus stepped away from her lab on Aug. 1 of last year to become the chief scientist of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

On the day the National Academy of Medicine announced it had elected her as a member in recognition of her work on drug metabolism and pharmacogenetics, ASBMB Today spoke to Bumpus about the new job, her career, and what academic scientists may not know about the FDA. This interview has been condensed and edited.

What does being chief scientist at the FDA entail?

It’s broad; it’s thinking strategically about the scientific mission of the FDA. We have dozens of research labs here doing outstanding work in all areas of public health. I try to think about where we have intersections across the agency and how we can work together and amplify the message of science at FDA. I think people don’t realize that we are scientists and have labs. We have scientists doing innovative research across the FDA.

The Office of the Chief Scientist has a range of components with diverse expertise and functions. For instance, a major part of my office is the National Center for Toxicological Research in Arkansas, where they perform original basic science research to investigate questions we need to answer to make some of our regulatory decisions; there are labs with a focus on drug safety and toxicology, artificial intelligence, and systems biology, among other areas. The scientific expertise and capabilities there are leading-edge, and the scientists contribute greatly to the FDA’s public health mission. My office also handles memoranda of understanding with other institutions through our technology transfer staff if we’re collaborating and transferring technology or inventions to make them more available.

We also have the Office of Scientific Integrity, which does many things that any scientific integrity office does but also some very FDA-specific things. For instance, this office coordinates for the Office of the Commissioner on hearing requests when matters arise in which the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act or FDA regulations require an opportunity for a hearing.

The Office of the Chief Scientist also helps manage advisory committees through our Advisory Committee Oversight and Management Staff. FDA advisory committees provide advice to the FDA around certain regulatory decisions. One of my priorities is to determine whether there are ways we can optimize the advisory committee process. We also have an Office of Laboratory Safety.

The Office of Scientific and Professional Development leads FDA training initiatives, including certain research fellowship programs. And through our team in the Office of Regulatory Science and Innovation, we fund science both intramurally and extramurally, including through our FDA’s Centers of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation program — a collaborative scientific partnership between the FDA and academic institutions. Our Office of Counterterrorism and Emerging Threats has deep expertise in policy and science around medical countermeasures and preparedness, and they play a central role in our preparedness efforts.

How did you decide to apply?

What got me interested in this role was the opportunity to take the science that I’m really interested in, which is pharmacology, and apply it and have a bigger impact than I felt I could in my lab alone. I love having a research lab. I love training graduate students and postdocs and making interesting findings. But to be able to take that expertise and collaborate with people on so many different scientific questions all related to advancing public health is what really drew me. I am excited about the breadth of areas that I’m able to work in with regard to both science and policy.

I believe that with my background, coming from academia, I am contributing a lot as far as the way we think about science and research at the FDA, and at the same time I’m learning and growing tremendously. For instance, I’m learning about policy and regulation and how science informs those areas.

Tell me about some of the research that FDA labs are doing?

One area that my office is particularly excited about is microphysiological systems — people all over the world are working on organs on a chip. And several labs here are doing work in those areas, thinking about how we can validate them — how we can use the liver on a chip to predict drug toxicity, for example. We have collaborations across the agency, and we’re starting to pull people together and talk about those data collectively. We’re also working around AI and machine learning to see how we can move that forward to enhance public health.

At the FDA, we serve a public health mission and work within the context of regulatory science. We’re also engaged with the broader international science community in thinking about how we can advance and validate technologies and what kind of unique perspective we can bring to stimulate discovery.

What does regulatory science mean, exactly?

It’s a science that’s focused on the scientific and technical foundation that underlies public health and the products we regulate. It’s the development of tools, standards and approaches that can be used to understand the safety, efficacy, quality and performance of FDA-regulated products. It’s broad, and of course it applies to devices, biologics and food, among other things — not only drugs.

We’re not necessarily doing discovery science. There is certainly discovery involved, and it’s highly intellectual and innovative, but it’s very much focused on regulatory questions: How can we predict toxicity from a drug or a chemical in food? Are there technologies that can do that? Are there in silico tools that can be used to simulate data so a new study doesn’t need to be done? Those types of things underpin regulatory decisions.

You’ve been in the role for a little over two months now. Do you still have trainees who are wrapping up at Johns Hopkins?

Yes. They have local advisers. The lab is now being led by a talented scientist, Ben Orsburn. We worked closely together for the past couple of years, and he is now taking the lab in innovative and interesting directions, such as work to advance single-cell proteomics. It’s very exciting stuff.

This move was not an everyday thing, but I felt well supported by everyone in the laboratory, the department and at Hopkins that it was an opportunity I had to pursue. I also, of course, miss being a department chair and the amazing department family in pharmacology at Hopkins.

So far, do you find scientific leadership in government different from in academia?

There’s a lot of overlap; I certainly felt well prepared. A lot of it is about making decisions and thinking about the next studies to do and how best to utilize resources — all things we’re trained to do in academia.

In academia, you work on teams, but they tend to be around a specific project or area of focus. Here, it’s even more team oriented; we’re a team on everything we work on. My office gets to interact with people in many product areas and learn from them and try to provide scientific expertise and support. It’s more of a collaborative focus because we’re trying to move forward on one mission, and I really enjoy that.

As you think about your career, what influences or mentors have contributed to you being ready to take on this role?

It’s every step along the way. I always cite my grad school and postdoc advisors, Paul Hollenberg and Eric F. Johnson, respectively, for preparing me to be a scientist, because at the end of the day, I really lead with my science. I’m not just a leader or administrator; I’m a scientist. I want to look at data and talk about what experiments we should be doing and our strategy for moving the science forward. As many people know, I am deeply committed to equity and social justice; I’ve always told mentees that leading with science and focusing on your love of science gives you a strong platform to make a difference in the culture of science in addition to contributing through the discoveries you make.

My graduate advisor taught me how to be a scientist and told me I could do anything. Then, at Hopkins, lots of people were in my corner. My dean, Paul Rothman, appointed me to be a department chair, giving me a leadership opportunity that was a chance for me to grow my skills and be proven and tested and to mature as a leader so that I was able to step into this opportunity.

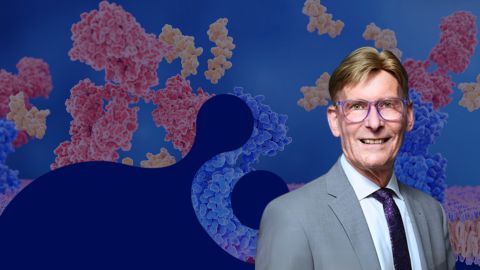

Each step, I’ve been lucky to have lots of supporters. Here, our commissioner, Robert Califf, also had a career as an academic, so we have a good understanding and communication. He values basic science as well as translational science. I feel I can really make an impact because I have support from that top level.

What else would you like ASBMB Today readers to know about the FDA?

People are surprised that we have research labs and by the breadth of techniques and approaches our people are using. We have a lot of expertise here and really outstanding scientists. It’s a place people should consider for scientific research careers.

We have training opportunities for scientists at various career stages and a lot of people who are very excited about mentoring in and outside of the lab. It’s a very collaborative environment, more so than people would expect. It’s a great place to start a career and a great place to be as a scientist. I’m learning a lot, but I’m still using my scientific chops all the time.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.