500 Queer Scientists: Increasing LGBTQIA+ visibility in STEM one story at a time

As a bisexual scientist, I sometimes feel like I have to hide my sexual identity in the lab. When a colleague and friend from a neighboring lab told me she was pansexual, I was glad I could talk to her about things like celebrating pride month and was just overall happy someone like me was there.

Queerness is a part of personal identity, yet often in science, technology, engineering and mathematics workspaces, we can feel we need to keep our queerness hidden because we might be considered unprofessional for speaking about it. As a result of this hiding, a queer person may feel alone and underrepresented in their field.

When I first heard about 500 Queer Scientists, a website where I saw scientists like my colleague and me, I wanted to find out more, so I got in touch with Lauren Esposito, a curator of arachnology at the California Academy of Sciences who runs a research lab focusing on the biology and evolution of spiders and scorpions. I asked Esposito to tell me how 500 Queer Scientists got started.

In spring 2018, Esposito helped with an event held at the academy in collaboration with 500 Women Scientists, an organization that works to make science more inclusive and accessible. Esposito, who uses she/they pronouns and identifies as queer, was happy to be in a space that empowered women, but at the same time, they felt they did not truly belong.

After the 500 Women Scientists event, Esposito reflected on their experience of not having queer scientists around them and not being able to express queerness in the lab.

“That sense of your own personal identity being unprofessional is really psychologically damaging and makes science not really, necessarily feel like a space that’s welcoming for queer and trans people,” they said.

This led Esposito to create 500 Queer Scientists, a campaign to increase LGBTQIA+ visibility in STEM.

At 500 Queer Scientists, scientists submit their own biographies and share stories about how they identify, what they do in STEM and how they experience being a queer scientist. So far, the site has 2,000-plus stories and counting.

I contacted three of the scientists to ask why they shared their stories.

Jui-Lin Chen is a postdoctoral researcher and immunologist at Weill Cornell Medicine. “I want to be out there saying, ‘hey, there are also some gay scientists out there trying to use their knowledge to improve human health and advance human knowledge,’” Chen said. “It’s also okay to be gay in science fields.”

Aflah Hanafiah, a Ph.D. candidate at Pennsylvania State University, wanted to show that trans people are diverse and have multiple backgrounds. By sharing her story, she hopes to start discussions. “If you only know one person of that particular background, you have to question why are they the only one,” she said. “Why is it that we don’t see more, and what can we do to support a more diverse group of scientists?”

Bernie Santarsiero, a research professor at the University of Illinois Chicago, wants to be part of an environment where people feel safe to come out and explore their sexuality.

“There’s been a few cases where individuals have come out to me that hadn’t been out before because they feel like there’s somebody that they can talk to, somebody they can approach,” he said. “It creates a better environment for you to be a better scientist, to be able to not have to hide a part of your life but be able to be open about it as well as go ahead and explore your own career and be successful in your career.”

Advocating for vaccines

As a first-generation immigrant from Taiwan, Chen, who is gay, encourages people from other countries to pursue science in the United States despite the cultural and systemic differences.

During his Ph.D. at Duke University, Chen combined nanomaterials to develop next-generation HIV vaccines. As a postdoc, he has continued this HIV vaccine research. He also studies how children respond to COVID-19 vaccines, with the goal of developing better vaccines for them.

The most enjoyable thing about being a vaccine scientist is “the feeling of contributing to society, that you are using your knowledge and all your skills to improve human health,” Chen said.

He recently created a science blog called The Immunologist where he shares immunology concepts and research in a fun and accessible way.

Because North Carolina is a conservative state that had just passed House Bill 2, an anti-LGBTQIA+ bill preventing transgender people from using bathrooms that aligned with their gender identity, Chen was initially worried about going to Duke for his Ph.D. But he was grateful that Duke turned out to be a very liberal school; an LGBTQIA+ student group worked hard to help people feel comfortable on campus. This group was his first source of support. Then, one day, one of his Ph.D. colleagues revealed to Chen that he was gay too, and they became best friends.

Moving for meaning

As a trans Muslim woman, Aflah (who generally uses a single name) grew up in Malaysia, a country where homosexuality is classified as a criminal offense, with no LGBTQIA+ rights and no laws to protect the LGBTQIA+ community from discrimination and hate crimes. In Malaysia, queer people can face many possible challenges, from being forced to undergo conversion therapy to sacrificing their identity. This made it especially meaningful for her to declare and celebrate her identity in the U.S.

Aflah works in an epigenetics lab, where she studies the role of polycomb repressive complex 1, or PRC1, in mammalian systems. PRC1 is a group of protein complexes involved in the expression of developmental genes in plants, insects, and mammals. She works with stem cells as well as mice.

Since Aflah was a child, she’s been captivated by the mechanics of life. In her home country, she excelled in high school and obtained a scholarship, allowing her to move to the U.S. and continue her scientific studies. This move took her away from a queerphobic country where she was not safe. “I needed to get out so that I would have the chance to actually live and lead a life that’s meaningful,” she said.

Aflah has a small group of trusted friends she calls her chosen family. “Honestly, I’m very happy,” she said. “It’s only a couple of people that I really, really trust that’s like my people. And that’s all you need.”

She connected with these friends through shared experiences of being foreigners, international students or of minority backgrounds. She advises anyone looking for similar support to be careful whom you trust and to trust yourself first and foremost.

“When you don’t have a community, you have yourself,” she said. “So have that very strongly in you, navigate your life, and find your people when you can and try your best to form that small community.”

On the margins and outside the box

Santarsiero, who is gay and Latino, has helped build programming at UIC for underrepresented and marginalized students in STEM and biomedical research at various stages in their academic careers. He helped lead the Latin@s Gaining Access to Networks for Advancement in Science, or L@s GANAS, program for Latinos and Hispanics, the DuSable Scholars Program for Black and Native American students, and the NIH-funded Portal to Biomedical Research Careers Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program, or PBRC PREP, for underrepresented minority groups, all of which aim to reduce equity gaps for students of color.

Santarsiero’s past research focused on biochemical systems and drug discovery with an emphasis on innovative approaches to developing new drugs. He co-led a group at the Novartis Institute of Functional Genomics and co-founded a small drug discovery company called Syrrx, which developed and used robotics to accelerate multiple stages of drug discovery, including gene cloning, protein expression, crystallization and data collection. In 2003, Santarsiero and his partners sold Syrrx after developing a few drug leads that were useful in treating diabetes.

As a professor in the College of Pharmacy at UIC, Santarsiero talks about ways to optimize pharmaceutical health care — these include teaching doctoral students and future health practitioners to be truly accepting and create a safe environment to make their patients feel comfortable.

“I think you want individuals to be open because that is the optimal way that you can actually help them in terms of being able to, in your own craft, support them,” he said.

Santarsiero also believes teams should be diverse in terms of race, ethnicity or gender, and sexuality.

“It’s the most efficient, creative way that individuals can actually attack a problem,” he said. “You don’t want to surround your people with, simply everybody has the same point of view or same background, same perspective, because then you’re not really going to be able to kind of think outside the boxes easily.”

Building a community

I was inspired by hearing these stories directly from their sources, and I’m grateful that a site like 500 Queer Scientists exists. I hope more people continue to share their stories on this platform.

As 500 Queer Scientists evolved, it became not only about sharing stories on the website but also about making virtual connections. Scientists have the option to include their Twitter/Instagram handle or LinkedIn URL along with their bio submissions. In this way, others can reach out to them personally.

“Oftentimes queer people are in isolated labs all over the country, all over the world,” Esposito said. “Or sometimes they’re in spaces where it’s not safe for them to talk about their identity openly. But by connecting virtually, there’s ways to share in the community and share in your identity that sometimes you can do sort of secret or through an alternate personality.”

And building community was a driving force behind the creation of 500 Queer Scientists.

“What I’m most proud of is finding my own community, like going from feeling really alone to feeling like there’s a community out there,” Esposito said. “And then I’m far, far from the only one in the room. ... I was looking for my community, and I feel really proud that I’ve been able to find that community and connect with people all over the world that share my identity.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

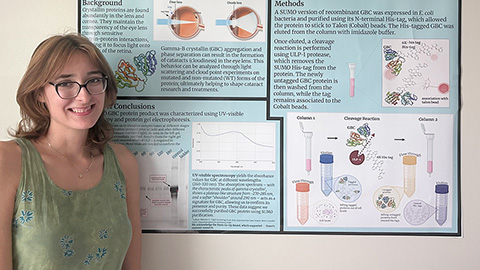

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.

How AlphaFold transformed my classroom into a research lab

A high school science teacher reflects on how AI-integrated technologies help her students ponder realistic research questions with hands-on learning.