Scourge below the surface

For shrimp and shrimp farmers, white spot syndrome virus is bad news.

Outbreaks of the virus can be economically devastating: It wreaked so much havoc in the Ecuadorian shrimp industry in 1999 that the country’s economy collapsed and the government was forced to adopt the U.S. dollar as the national currency in 2000.

The virus was first detected in Taiwan in 1992. From there, it spread throughout Asia, including India and the Middle East. It landed in the Americas in 1995, thought to be transported through frozen shrimp bait from Asia, at a south Texas shrimp farm. The virus has also appeared in Mozambique. The virus doesn’t infect only shrimp; other aquatic animals, such as crayfish, plankton and crabs, can carry the virus.

When shrimp get infected with WSSV, they develop visible white spots in their shells just before they die. Tools have been developed to detect the virus, which have helped to eliminate contaminated shrimp stocks. But lapses of oversight still occur, and outbreaks still happen. The problem is that once the virus infects shrimp there isn’t a way to treat the infection.

Mastering a new species

Until WSSV appeared, marine viruses were thought to be ecologically unimportant, because their types and numbers were underestimated. For this reason, marine viruses are less understood than other types.

WSSV is a new beast in terms of species: A new family (Nimaviridae) and genus (Whispovirus) had to be created just to accommodate it. Under the microscope, the virus resembles mammalian sperm, with a round head and a flexible tail.

The viral DNA was first isolated in 1997 and shown to be a double-stranded, circular molecule. By 2005, at least three different strains from various Asian locations had been sequenced. Genomic analyses have shown that “most of the approximately 180 genes included in the genome had unknown functions,” explains Timothy Flegel at the National Science and Technology Development Agency and Mahidol University in Thailand. “It is our belief that studying the functions of the mystery genes and understanding how they interact with host shrimp genes and even with each other will reveal new ways to combat the virus, in terms of both preventing infections and therapy after infection.

In a recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics paper, Flegel, Chu-Fang Lo at the Cheng Kung University in Taiwan and colleagues described a proteomic analysis of WSSV in an effort to better understand how the virus functions and interacts with its host. The investigators used yeast two-hybrid screens to look at more than 700 possible interactions between about 180 proteins. To confirm that the interactions they saw were not experimental anomalies, the investigators then performed coimmunoprecipitation assays and other analyses.

Clinical signs

Thailand is the world’s leading exporter of shrimp. Over the past couple of years, it has been hit hard by yet another disease, known as early mortality syndrome, which has reduced significantly shrimp production in the region and has driven up global shrimp prices to a 12-year high in 2013. The cause of EMS recently was found to be bacterial.

|

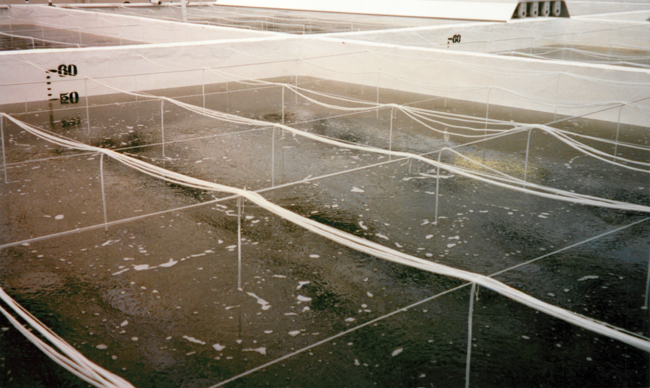

Stephen G. Newman/AquaInTech Inc.

Whiteleg shrimp, also known as Pacific white shrimp, has gained in popularity over the past decade, in part because genetically screened, virus-free broodstock is available.

Stephen G. Newman/AquaInTech Inc.

Birds picking off infected shrimp.

|

Timeline

- 1992: Taiwan reports the first WSSV epidemic.

- 1993: The Chinese shrimping industry is crippled by it, and Japan and Korea have outbreaks.

- 1994: Thailand, India and Malaysia have outbreaks.

- 1995: WSSV is reported in the U.S.

- 1997: Viral DNA is isolated.

- 2005: Three strains have been sequenced.

- 2013: All shrimping regions have been affected.

This mapping of protein-protein interactions within a virus is a first for “a shrimp virus or virus of any other invertebrate,” says Flegel. Identifying hub proteins is important, because these proteins are thought to be central to various viral functions.

“This work clearly demonstrates the importance of several proteins for WSSV replication and disease progression and presents them appropriately as excellent future targets for antiviral therapy,” says Fraser Clark at University of Prince Edward Island in Canada, who is an expert in marine viruses but not involved with the research in the MCP paper. “These hub proteins could represent excellent targets for future antiviral therapy through interfering RNA, small-molecule inhibitors or antibodies capable of disrupting protein signaling.”

The next step, say Flegel and Clark, is to generate a protein-interaction map between WSSV and shrimp proteins.

“Many studies have shown the interaction of shrimp and WSSV proteins, but an extensive interaction map would demonstrate the importance of a subset of proteins that could be targeted for antiviral therapy,” explains Clark. “WSSV hub proteins are critical once infection has been established, but the disruption of the initial WSSV and shrimp protein interactions that facilitates infections could potentially prevent WSSV infections from becoming established in the first place.”

Editor’s note: Many thanks to Stephen G. Newman, marine microbiologist and president and chief executive officer of AquaInTech Inc., for his help with illustrating this article. AquaInTech, based in Lynnwood, Wash., supplies science-based products, tools and services to the international aquaculture community. Find out more at www.aqua-in-tech.com.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.