From the journals: JBC

A transient receptor potential channel distinguishes “hot” from “pot.” Higher liver glycogen storage turbocharges mice. Blocking steroid hormone synthesis blocks cancer. Read about recent papers in the Journal of Biological Chemistry on these and other topics.

How a TRP channel tells “hot” from “pot”

Transient receptor potential V1, or TRPV1, is an ion channel that performs double duty, recognizing both high heat and a range of small molecules that includes both the spicy compound capsaicin and peptide toxins found in venom. The receptor, which is expressed in pain-sensing neurons, is responsible for translating all these stimuli into pain.

But TRPV1 also binds endocannabinoids, lipid signals that are not usually noxious. And although it is not their major receptor, TRPV1 also responds to active compounds found in cannabis. This is a bit odd since, unlike other TRPV1 ligands, endo- and exogenous cannabinoids are generally not a noxious signal. The receptor is not a primary mediator of cannabinoid signaling — but could it nonetheless be linked to the anti-pain properties of endocannabinoids and their herbal counterparts? Although structures of TRPV1 have been solved, researchers do not understand fully yet how it interacts with its diverse ligands.

In a recent article in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Yanxin Li, Xiaoying Chen and colleagues at Zhejiang University School of Medicine and Qingdao University Medical College write that they used molecular docking to investigate how endocannabinoids bind to TRPV1 and patch-clamp recording to determine the effects of interaction on channel opening.

They found that the general orientation in which endocannabinoids such as anandamide bind to TRPV1 is similar to that of other compounds such as capsaicin. However, cannabinoids engage a crucial tyrosine residue within the protein that does not participate in binding to capsaicin. The authors conclude that the channel’s mechanism for opening differs between the two types of ligand, perhaps explaining the different effects of these compounds on pain sensation.

Glycogen storage turbocharges mice

Energy storage and release are important for performance in endurance exercise. Glycogen, a highly accessible glucose storage form, is typically the first energy source used during activity; an animal’s endurance capacity may depend in part on the extent of its glycogen stores. Mammals store glycogen in liver and muscle cells. While depletion of muscle glycogen is known to cause fatigue, researchers know less about how liver glycogen contributes to endurance capacity, although lengthy exercise is known to lower liver glycogen.

In a recent article in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Iliana López–Soldado and a team at the Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology describe their study of mice overexpressing a gene that drives glycogen synthase activation in liver cells. They tested the animals’ ability to sustain a low-intensity run, which they compared to marathon training in humans. Animals with this modification maintained higher glycogen in their livers after exercise and showed longer endurance. They also were less sensitive to a reduction in performance while fasting than wild-type mice. The results indicate that liver glycogen is an important source for supplementary energy to power endurance activity.

Blocking hormone synthesis to block cancer

A subtype of cytochrome P450, P450 17A1, catalyzes two steps in the production of androgens: hydroxylation of steroid precursors to androgens and glucocorticoids and a second oxidation reaction that is specific to testosterone and other androgens. Human physiology depends on glucocorticoids, so blocking the cytochrome’s second oxidation activity without affecting the hydroxylation is a goal for treatment of androgen-dependent prostate cancer.

In a recent article in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, F. Peter Guengerich and colleagues at Vanderbilt University write that they investigated inhibition mechanisms of drugs that block steroid hormone synthesis, which were designed as a treatment for hormone-dependent cancers such as prostate cancer. They found that all five of the compounds they tested bound to the cytochrome without a need for further changes and inhibited both types of reaction. The finding indicates that more work will be needed to develop a compound that can block one activity and not the other.

Proteins poised to battle pathogens

Researchers studying a channel-forming protein that works as a weapon against parasitic protists have found that the protein’s homologs may be geared toward other types of pathogen.

Apolipoprotein L1, first found in a small subset of high-density lipoprotein particles, is involved in immune signaling and upregulated during infection. Apolipoprotein L1 can integrate into lipid bilayers, forming cation channels that eventually kill cells. This makes it a useful weapon against extracellular eukaryotic parasites like trypanosomes; after ApoL1 breaches their membranes, cations flow into the cell, and osmotic swelling and lysis ensue.

Humans and other primates express five more apolipoproteins homologous to ApoL1, called ApoL2-6, whose channel-forming properties have not been studied. In the Journal of Biological Chemistry, Jyoti Pant and colleagues at the City University of New York report on a study of whether ApoL 2-6 are able to puncture membranes the same way that ApoL1 can. They found that some of the proteins can, when overexpressed, cause cells to swell and release lactate dehydrogenase; others cannot. The six apolipoproteins tend to be expressed in different cellular compartments, suggesting that they might protect against pathogens not just outside the cell, such as trypanosomes, but also internal pathogens.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

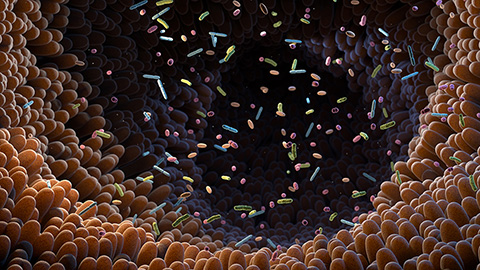

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

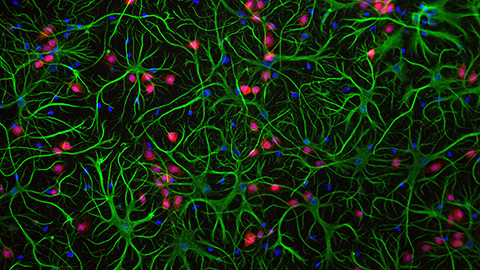

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.