From pigeon guano to the brain

Between 1 million and 3 million species of fungi exist on Earth, but fewer than 200 have been reported to cause human infections. It makes you wonder: Why are some fungi fantastic while some are fatal?

For Fungal Disease Awareness Week, I zeroed in on two infectious fungi in the genus Cryptococcus, which contains over 100 species. C. neoformans and C. gattii cause most of the cases of cryptococcosis in humans.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention most C. neoformans infections occur in people with weakened immune systems. It causes 220,000 cases of meningitis worldwide annually among people with HIV/AIDS, resulting in 181,000 deaths, equivalent to the population of a small country, such as St. Lucia. This pathogenic fungus takes a particularly large toll on people in sub-Saharan Africa.

C. neoformans presents as a complex syndrome that can be challenging to diagnose. The CDC lists its symptoms as fever, fatigue, dry cough, headache, blurred vision and confusion. Diagnosis is usually confirmed by laboratory evaluation.

Joseph Heitman, a physician–scientist and chair of the Department of Molecular Genetics and Microbiology at Duke University School of Medicine, has been studying this and other fungal pathogens since 1994.

“Humans get exposed to it by inhaling the infectious propagule, which is either desiccated or dried yeast cells or spores or both,” he explained. “After the initial pulmonary infection, it spreads through the bloodstream to infect the brain, both the meninges and the parenchyma of the brain, causing meningitis and meningoencephalitis. So, patients can have pneumonia, they can have meningoencephalitis, (and) they can present with both.”

C. gattii, meanwhile, can cause illness in healthy people. The CDC notes that C. gattii has been infecting people (and animals) in California since at least the 1960s. It then began to pop up in Canada and the Pacific Northwest in the early 2000s, and it has since been found in the Southeast.

The basics

Cryptococcus is an environmental fungus found all around the world in soil and is usually associated with bird droppings. While soil contaminated with pigeon droppings is the major environmental source for C. neoformans, eucalyptus and other trees and decaying hollows in living trees are the major reservoir for C. gattii.

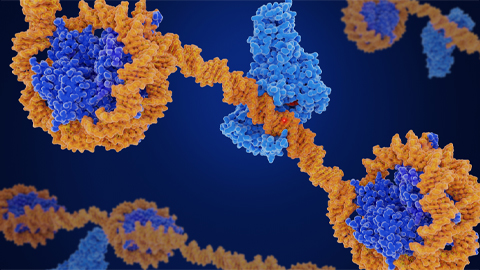

Members of the Cryptococcus genus are characterized by elongated, yeastlike cells. When two cells of opposite sex mate, they form filaments, which grow and eventually produce tiny basidiospores. Interestingly, this fungus exhibits different forms of sexual, asexual and pseudosexual reproduction cycles.

Guano goes global

Whereas C. neoformans is a globetrotter, C. gattii is more of a homebody.

“Many fungi are cosmopolitan, and you find them everywhere. And other fungi are provincial, and they have a much more restricted environmental niche or geographic distribution,” Heitman said.

Heitman offered as an example Histoplasma, which is found in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys. “It is geographically restricted to a region,” Heitman said.

He continued: “On the other hand, Cryptococcus occurs in both patterns. There is one type — Cryptococcus neoformans — which is cosmopolitan. It’s all over the world. And that’s the one that's associated with pigeon guano.”

According to Heitman, in the 14th and 15th centuries, seafaring ships went all over the planet — and they carried carrier pigeons with them. This fungus that had learned to live on pigeon guano is thought to have swept across the globe along with the ships.

Discovering Cryptococcus and its consequences

The genus Cryptococcus was established by German pharmacist and phycologist Friedrich Traugott Kützing in 1833. After a detailed classification, this particular fungus was included in the Cryptococcus genus by Vuillemin in 1901. The “Crypto” part of the name is derived from the ancient Greek word “Kryptos” meaning “hidden.” The “coccus” part means “berry” (reflecting the spherical shape of the yeast).

In a 1995 review article covering a century of research on C. neoformans, Thomas G. Mitchell and John R. Perfect noted that it was isolated from peach juice in Italy and a sarcomalike leg wound in Germany in 1894. “Many of the early case reports were associated with patients with cancer,” Mitchell and Perfect wrote.

Around the same time, according to a 2014 review by Kyung J. Kwon-Chung and colleagues, a third researcher found a similar but different yeastlike fungus in a patient’s hip tumor. It was later determined to be C. gattii.

David Paul von Hansemann presented the first report of cryptococcal meningitis in 1905.

It was Chester Emmons who, in the early 1950s, first isolated C. neoformans from soil from a farm in Virginia.

Over the years, there’s been a lot of debate about classification and nomenclature, the latter of which continues to this day.

“Confusion about the identity of the cryptococcosis agent persisted until (Rhoda W.) Benham performed (in the 1930s and 1950s) comprehensive studies with clinical Cryptococcus strains and concluded that all of the strains from human infections belonged to one species with two varieties based on serological differences,” Kwon-Chung and colleagues wrote.

In 1964, Emmons and John Utz, both of the National Institutes of Health, asked doctors to be on the alert for crypto-caused meningitis. This raised the ire of those at the Humane Society of America, according to the New York Times. A society official, the Times reported, “cited a pro pigeon scientific article” to refute Emmons and Utz’s claims.

But Emmons stuck to his guns. “Old pigeon droppings constitute the only source so far where we can consistently find the fungus in large numbers,” he told the paper.

Treating Cryptococcus infections

In addition to demonstrating the yeast’s association with pigeon nesting sites, Emmons went on to showing that amphotericin B could be used as a treatment. It is one of the most common treatment options to this day, along with fluconazole and flucytosine.

These drugs are administered intravenously in hospitalized patients who are carefully monitored during treatment for any serious side effects. Doctors usually follow the guidelines from the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatments can last for a year or longer.

However, medical practitioners face multiple challenges for the successful application of anticryptococcal treatments, such as drug-related toxicity, difficult routes of administration, high costs of drugs, and lack of approval or availability of some drugs in some countries.

These challenges demand further research into the clinical and biological aspects of this pathogenic species.

Vaccine development

As the fungus has gained ground in terms of its different geographical niches affecting not only a large number of immunocompromised patients but also healthy individuals, the demand for a vaccine has grown.

Researchers are attempting to develop vaccines with heat-killed Cryptococcus cell-wall mutant, and they’ve had promising results in mice. Attempts are also being made to use fungal glycolipids, such as glycosylceramide, to develop vaccines.

“A major challenge in vaccine development is that the vaccine needs to be effective in patients with the weakened immune system, especially patients deficient in CD4+ T cells,” Heitman said.

Virulence factors

A major question remains: What unique features transform Cryptococcus into a prolific pathogen?

Heitman points to two molecules that help the pathogen evade immune responses: the capsule and melanin.

“The Cryptococcus capsule surrounding the cell is a very complex, polysaccharide-rich matrix, and it can inhibit phagocytosis and promote survival in the body,” he said.

Melanin, meanwhile, is a dark pigment embedded in the cell wall. Heitman said it “protects the cellular proteins from oxidation and nitrogen radicals.”

He added that it is interesting to note that Cryptococcus mutants that are defective in making capsule or melanin are either avirulent or are severely attenuated in the host.

The formation of Titan cells is another novel virulence factor that helps C. neoformans establish infection in the lungs. These giant cells not only evade the immune cells but also protect smaller cells to increase the fungal burden in hosts. (See box.)

Cryptococcus cannot be ignored

One of the lessons the world should learn from the recent COVID-19 pandemic and global warming is that in the coming years these fungal diseases will become more prominent worldwide, threatening not only the lives of millions of people but having detrimental effects on crop production and unleashing havoc on economies.

Heitman underscored: “The association of human disease and fungi is centuries old. We can no longer afford to neglect fungi, especially the silent killers.”

How Titan cells aid in infection progression

During infection, Cryptococcus cells escape from the host defense system by different mechanisms, such as growing to an unusually bigger size.

Joseph Heitman studies pathogenic yeast at the Duke University School of Medicine.

“A typical yeast cell is about 5 µm. But in the lungs of infected animals or patients, you find cells that are dramatically enlarged to 50 to 100 µm. And that's just their diameter. If you think about the volume of the cell, it's a gargantuan increase in size,” Heitman said.

These giant cells are known as Titan cells. Titan cells are formed in the early stages of infection and have distinguishing features that make them more pathogenic. These features include altered cell wall structure and compacted capsules. They are also more resistant to antimicrobial stress.

“Researchers are slowly understanding the importance of Titan cells in disease progression. These gargantuan Titan cells fight with the poor macrophage as it tries to get its pseudopodia around for phagocytosis, and it's just not big enough to be able to engulf this cell,” he said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Meet Paul Shapiro

Learn how the JBC associate editor went from milking cows on a dairy farm to analyzing kinases in the lab.

CRISPR epigenome editor offers potential gene therapies

Scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, created a system to modify the methylation patterns in neurons. They presented their findings at ASBMB 2025.

Finding a symphony among complex molecules

MOSAIC scholar Stanna Dorn uses total synthesis to recreate rare bacterial natural products with potential therapeutic applications.

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.