Using a network to snare the cause of kidney disease

Proteins in their correct shapes are the building blocks of properly functioning bodies. When proteins misfold or unfold, they malfunction, leading to life-threatening diseases.

The zinc-binding protein leukocyte cell-derived chemotaxin-2, or LECT2, is synthesized in liver cells for secretion into the blood. When misfolded, it aggregates in the kidneys and liver, resulting in organ failure and end-stage kidney diseases. Accumulation of misfolded LECT2, called LECT2 amyloidosis, or ALECT2, is most common in Hispanic adults; it has no known biomarkers, and the only diagnosis option is a kidney biopsy.

In ALECT2 patients, both copies of the LECT2 gene harbor a mutation, which researchers think contributes to the disease. This mutation is common in the general population, however, leading researchers to believe that other physiological stressors act in concert with the mutation to cause ALECT2. Leading candidates for these stressors are loss of LECT2’s bound zinc ion and flow shear as the protein travels through blood vessels.

To learn more about this relationship, Stewart N. Loh’s team at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University and Dacheng Ren’s lab at Syracuse University designed a microfluidic device to mimic blood flow through the human kidney. They recently published a paper about their work on the aggregation of LECT2 in kidney disease in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

“We can do benchtop assays or go to animal models for biological studies,” Ren said, “but none of those systems have real-time observation capabilities, and here the microfluidic device comes into play.”

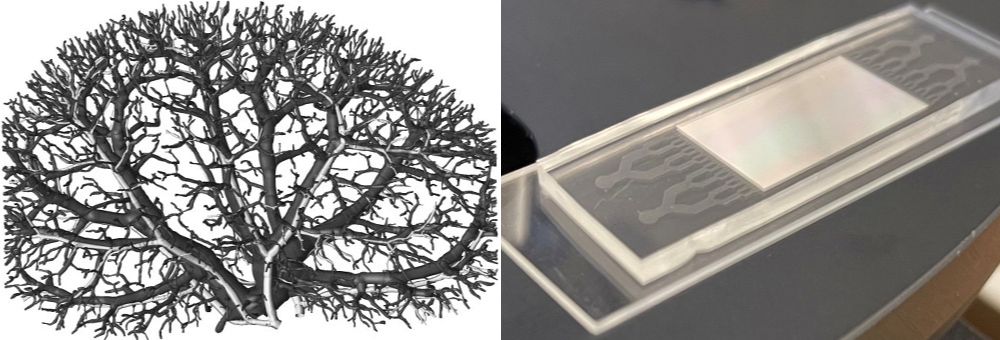

Ren’s team created a microfluidic chip mimicking the blood capillaries in a kidney. The researchers individually pumped wild-type and mutant LECT2 proteins purified by Loh’s team into the device at the physiological flow rate.

“Dr. Ren’s lab recorded images in real time as the protein was aggregating at the smallest channels corresponding to the smallest dimensions of kidney that go into the glomerulus,” Loh said, “and you could see the protein is clogging those channels going upstream, resembling what you see in kidney diseases.”

The researchers calculated the density and percentage of aggregates clogging the channels at a specific time to compare how the wild-type and the mutant aggregates formed. They then used cryo-electron microscopy to observe the aggregates under stress.

The study showed for the first time two conditions that may combine to cause ALECT2 — the mutation along with loss of zinc ion and the kidney-like flow shear inducing ALECT2 in the absence of zinc.

“The next step will be adding serum albumin or changing the viscosity in a controlled way and finally using the whole blood or serum to study the actual system,” Loh said. “Our program is geared toward developing a biosensor and tools to detect these misfolded proteins in the blood before they have a chance to build up in the organ.”

Ren said the microfluidic device could be used to study the real-time behavior of biomolecules in organisms and to diagnose other circulating misfolded proteins.

“The device could potentially be scaled up for high-throughput screening studies in future,” he said.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid–protein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the ASBMB annual meeting.