From the journals: JLR

An oil check that might be key to brain health. A deletion that reveals more than meets the eye. What cholesterol does between cells. Read about papers on these topics recently published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

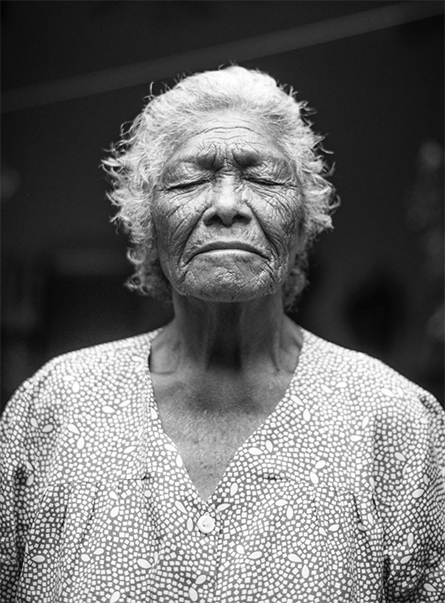

This oil check might be key to brain health

diseases by 2030.

Chances are, you know someone affected by dementia — an umbrella of neurodegenerative conditions encompassing Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and other diseases that affect about 50 million people worldwide. Drugs developed to treat these conditions have been largely ineffective. However, a new study in the Journal of Lipid Research by Larry Spears and colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis links a lack of the lipid plasmalogen to the vascular abnormalities associated with these brain diseases.

Plasmalogens are the most common type of phospholipid in the tissues of the nervous system and help protect the brain against oxidative stress, which is known to cause progressive neurodegenerative conditions. Plasmalogens are produced by the endothelial cells that make up the blood–brain barrier, vital for the protection of the brain. Hence, these lipids play two key roles in protecting the brain and keeping it running smoothly.

The authors of this study genetically altered mice so their endothelial cells would have no PexRAP, an enzyme necessary for the synthesis of plasmalogen. Without PexRAP activity, circulating levels of plasmalogens decreased. This resulted in behavioral changes in the mutant mice and structural changes in their brains that are synonymous with neurodegeneration. The behavior changes included decreased physical activity, decreased attention to their environment and impaired spatial memory. Structurally, the number of neuroprotective glial cells increased, signaling a reaction by the nervous system as it sensed damage due to the lack of plasmalogens. In addition, the researchers saw a decrease in tyrosine hydroxylase activity, a consequence of neurodegeneration.

The authors concluded that plasmalogen decreases in the nervous system after vascular damage, leading to impaired brain health. Hence, checking on the levels of the brain’s oil, plasmalogen, could serve as an indicator of brain health.

Deletion reveals more than meets the eye

Sphingolipids more commonly are known by their precursor, the popular skincare ingredient ceramides. However, these lipids play a more critical role in a host of physiological processes such as programmed cell death and inflammatory cascades, yet researchers know little about their regulation.

A recent study in the Journal of Lipid Research by Christopher Green and colleagues at Virginia Commonwealth University highlights the complexity of regulating sphingolipid biosynthesis. The researchers investigated the role of the different functional forms of mammalian ORMDL, a protein that negatively regulates the activity of serine palmitoyltransferase complex, or SPT, the enzyme driving sphingolipid biosynthesis. Using a gene-editing tool, the authors developed stable, carcinogenic human lung cells with various functional forms of ORMDL to detect the unique roles of each form.

The results show how these various functional forms of ORMDL uniquely affect sphingolipid metabolism, such as by determining the production of certain sphingolipid groups or by increasing the levels of certain ceramide species over others. These effects have broad implications for the critical body functions, such as cell growth and motility, that require sphingolipids.

What cholesterol does between cells

Two hundred years after Robert Hooke discovered cells, scientists got curious about the invisible barriers surrounding animal cells. Almost 50 years later, researchers described the dual nature of the fluid mosaic model of the cell membrane as both hydrophobic and hydrophilic due to its lipid and protein components. Chief among the lipids is cholesterol.

Cholesterol allows for a firm yet permeable cell membrane and is involved in steroid production. Now, a new study in the Journal of Lipid Research by Pawanthi Buwaneka and colleagues at the University of Illinois at Chicago has uncovered additional roles in cell signaling for cholesterol, specifically in the inner layer of the double-layered membrane.

Based on their previous work spotlighting interactions between cholesterol in this layer and intracellular proteins, the researchers’ recent experiments using various cell types including fibroblasts and Leydig cells illustrate how these interactions precede cellular signaling. Using advanced imaging analysis, the authors show how the level of cholesterol in the inner layer is tightly regulated to control intracellular signaling processes. This new role of cholesterol as a signal propagator could have implications for studying cell physiology.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

CRISPR epigenome editor offers potential neurodevelopmental gene therapies

Scientists from the University of California, Berkeley, created a system to modify the methylation patterns in neurons. They presented their findings at ASBMB 2025.

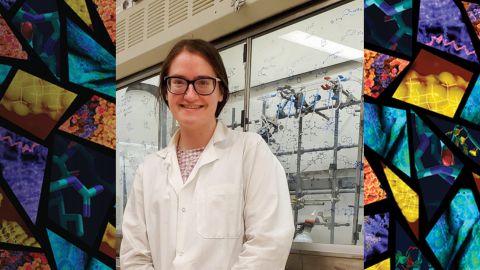

Finding a symphony among complex molecules

MOSAIC scholar Stanna Dorn uses total synthesis to recreate rare bacterial natural products with potential therapeutic applications.

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.