Ebola virus hides out in brain

The Ebola virus can hide in the brains of monkeys that have recovered after medical treatment without causing symptoms and lead to recurrent infections, according to a study by a team I led that was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Ebola is one of the deadliest infectious disease threats known to humankind, with an average fatality rate of about 50%. Ebola is known for a high level of viral persistence, meaning the virus remains lurking in the body even after a patient has recovered. But where this hiding place is remains largely unknown.

In 2021, there were three Ebola outbreaks in Africa, all linked to previously infected survivors. Ebola also reemerged in Guinea that same year, linked to a survivor of the 2013-2016 Ebola outbreak.

We wanted to better understand where the Ebola virus “hides” in the body of survivors and what triggers recurrent infections. So we examined 36 rhesus monkeys that had been treated for Ebola with monoclonal antibody therapy, a type of treatment that helps the immune system mount an attack against an infection. These monkeys were deemed fully recovered with no symptoms of infection or detectable virus in their blood.

When we looked more closely at the tissues of different organs under a microscope, however, we found that about 20% of recovered monkeys still had visible Ebola virus located exclusively in the ventricular system of the brain. This brain region produces, circulates and stores cerebrospinal fluid, which protects, supplies nutrients to and removes waste products from the brain.

Importantly, despite being asymptomatic at the start of our study, two of the monkeys we observed developed Ebola symptoms before dying at 30 and 39 days after their initial infection, respectively. Our findings suggest that the Ebola virus can hide dormant in the brains of survivors even after treatment, and the virus can reactivate and cause fatal infections later on.

Why it matters

Treatment with monoclonal antibodies is the current standard of care for Ebola. But recurrent infections can occur even after apparently successful treatment, and patients can inadvertently transmit the virus and cause new outbreaks.

Our study underscores the importance of careful long-term medical follow-up of successfully treated Ebola survivors to counter the individual and public health cost of recurrent disease. This follow-up, however, will need to be conducted in a way that does not further stigmatize survivors of the disease.

What still isn’t known

We still don’t know why the Ebola virus persists in the brain and causes recurrent infections. It is also unclear whether this persistence might be related to monoclonal antibody treatments, and whether other types of therapies, such as antivirals, might produce a different effect. Researchers are still looking into what triggers relapses and whether there might be other parts of the body that may act as reservoirs.

What’s next

Our work highlights the need to more deeply investigate why the Ebola virus persists in the brain. Because the brain is less accessible to monoclonal antibodies, treatments combining both monoclonal antibodies and antiviral drugs may help prevent and clear persistent Ebola infection and related disease in the brain. Analyzing viral persistence at the molecular level may provide more insight.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Mining microbes for rare earth solutions

Joseph Cotruvo, Jr., will receive the ASBMB Mildred Cohn Young Investigator Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Fueling healthier aging, connecting metabolism stress and time

Biochemist Melanie McReynolds investigates how metabolism and stress shape the aging process. Her research on NAD+, a molecule central to cellular energy, reveals how maintaining its balance could promote healthier, longer lives.

Mapping proteins, one side chain at a time

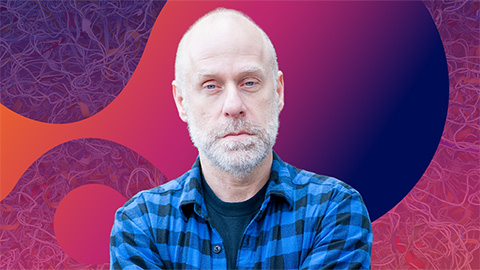

Roland Dunbrack Jr. will receive the ASBMB DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Exploring the link between lipids and longevity

Meng Wang will present her work on metabolism and aging at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Defining a ‘crucial gatekeeper’ of lipid metabolism

George Carman receives the Herbert Tabor Research Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.