MCP: Proteogenomics researchers find causes of immune disease

Routine clinical sequencing has given doctors unprecedented insight into genetic disorders. However, genomics fails to diagnose up to half of patients who are tested. That’s the problem that scientists at universities in Munich and Berlin tackled in a recent study in the journal Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. With samples from patients in four countries and a novel database on the neutrophil proteome, Christoph Klein and colleagues diagnosed two children with severe congenital neutropenia using mass spectrometry-based proteomics when typical sequencing had failed.

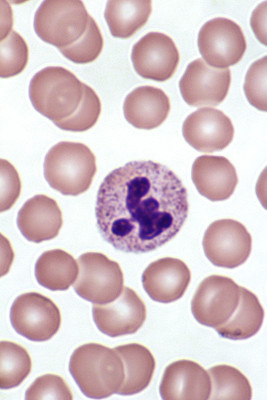

Neutrophils, like the one in the center of this photo, are loaded with granules full of proteases that make them difficult to study. Guy Waterval /Wikimedia Commons

Neutrophils, like the one in the center of this photo, are loaded with granules full of proteases that make them difficult to study. Guy Waterval /Wikimedia Commons

“There are very few examples of people who use multiple omics to investigate rare diseases … (but) I think this is the future of personalized medicine,” said Klein, a physician and director of the Children’s Hospital of the University of Munich.

The patients’ disease affects their neutrophils, white blood cells packed with toxic proteins to deploy against bacteria. When neutrophil development is disrupted, which Klein estimates happens to 1 in 200,000 newborns, every bacterial or fungal infection can become a life-threatening medical emergency.

Klein’s lab has studied rare genetic causes of neutropenia for years, but proteomics was a new field for the group. Postdoctoral researcher Sebastian Hesse met proteogenomics expert Juri Rappsilber at a conference, sparking a collaboration to study the proteome and transcriptome of neutrophil granulocytes.

Neutrophils are post-mitotic and very fragile, which makes studying them a challenge.

“You can think of them as suicide bombers,” Klein said, explaining that the cells are full of granules loaded with proteases that make retrieving other proteins a challenge. Hesse painstakingly developed a protocol to collect intact proteins and mRNA from healthy neutrophils.

Using mass spectrometry, scientists led by co-first author Piotr Grabowski in the Rappsilber lab at the Technical University of Berlin analyzed the cells’ proteome. When they added transcriptomic data, they found strikingly little correlation with the proteome, so they chose to focus on protein in patient samples.

Next, Hesse collected neutrophils from 16 patients with congenital neutropenia. Some were in Germany; to find others, he had to travel.

“These patients are from various parts of the world — that’s another unique challenge of working with rare diseases,” Klein said. “Sebastian flew to Iran and Turkey, in a collaborative effort with the pediatric hospitals there.”

Back at home, after processing and freezing the samples, Hesse handed them off to Grabowski; the proteomics scientists repeated the analyses to see what proteins had changed in the patients’ blood.

The team used abnormal protein profiles to guide the diagnosis of two patients with inconclusive exome sequencing results.

In one child’s case, a pseudogene made it difficult to identify mutations in the protein-coding gene; in the second, incomplete coverage by exome sequencing had missed a key point mutation. Data on protein abundance in each patient led the researchers to run more specific genetic tests that proved conclusive.

“This highlights (that) even if you have highly controlled pipelines for genetic studies, there’s always a risk that you are not 100 percent correct,” Klein said.

The researchers did not set out to make diagnoses from patient proteomes, but the study highlights the value proteomics data can add.

“Cellular proteome studies are not in routine clinical use at this point,” Klein said. “But … I think there will be huge potential for proteome analysis at a very low cost down the road.”

The team plans to expand its studies to other patients with immune deficiencies, looking for new genetic mechanisms of disease.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.