Bacterial protein reverses infertility by lowering cholesterol

In the United States, one in every five women of childbearing age is unable to get pregnant after trying for a year. Further, about 20% of these women face idiopathic infertility where the underlying causes are not fully known.

Now, Houston Methodist scientists have found additional evidence linking high cholesterol to female infertility. They also reversed infertility in sterile preclinical models by reducing high circulating cholesterol with a bacterial protein called serum opacity factor. Although the protein's primary function is to increase bacterial colonization, serum opacity factor alters the structure of cholesterol-carrying high-density lipoproteins or HDLs, making it easier for the liver to dispose of the excess cholesterol that is preventing conception.

“We are working with a very special protein with unique characteristics,” said Corina Rosales, assistant research professor of molecular biology in medicine and lead author on the study. "In our experiments, serum opacity factor lowered cholesterol levels by more than 40% in 3 hours. So, this protein is quite potent."

The researchers also noted that serum opacity factor's dramatic action on HDL could be leveraged as a potential alternative to statins, which are the current gold standard for lowering cholesterol in people with atherosclerosis.

The results of this work are published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

The workhorses of the fat metabolism processes in the body are lipoproteins that faithfully shuttle cholesterol and triglycerides to different cells of the body. Low-density lipoprotein or LDL carries cholesterol from the liver to other tissues. For that reason, LDL is often considered "bad cholesterol" since high levels of LDLs cause cholesterol accumulation and consequently diseases, such as atherosclerosis. On the other hand, HDL, the "good cholesterol," carries excess cholesterol from different tissues to the liver for breakdown, thereby bringing down cholesterol levels. But if there is HDL dysfunction, lipid metabolism gets altered, which could then be harmful.

“Both HDLs and LDLs contain a mixture of free and esterified cholesterol, and free cholesterol is known to be toxic to many tissues,” said Henry J. Pownall, PhD, professor of biochemistry in medicine and senior author on the study. “And so, any dysfunction in HDL could be a risk factor for several diseases.”

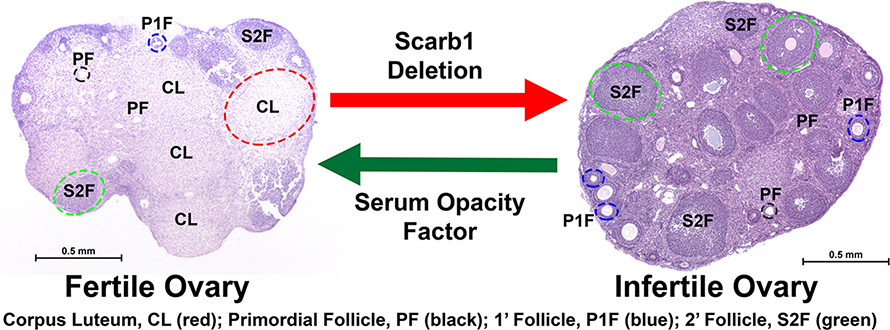

To study HDL dysfunction, the researchers worked with genetically modified mice that do not produce receptors for HDL. These animals have unnaturally high levels of HDL cholesterol circulating in their bloodstream, making them ideal model systems for atherosclerosis. But Rosales observed that these mice were also completely sterile.

“Cholesterol is the backbone of all steroidal hormones, and an orchestra of hormones is needed to have a fertile animal,” said Rosales. “We know that the ovaries are studded with receptors for HDL, so the metabolism of HDL had to play a very important role in fertility for that reason.”

As predicted, when the researchers fed the sterile mice with a lipid-lowering drug called probucol, both LDL and HDL cholesterol levels reduced, and the animals were temporarily rescued from infertility. Motivated by these results, they turned to a bacterial protein serum opacity factor that is known in the literature to be highly selective for HDL.

“Serum opacity factor is known mainly in the context of bacterial strep infections where it serves as a virulence factor. But it was also discovered that this protein only reacts to HDL and not to LDL or other lipoproteins,” said Rosales. “We hypothesized that perhaps administering serum opacity factor to these mice might help restore their fertility as well.”

For their next set of experiments, the team engineered an adeno-associated virus to deliver the gene for serum opacity factor to mice lacking HDL receptors and thus have high blood cholesterol. When the gene was expressed and the bacterial protein was produced, the animals' HDL cholesterol significantly lowered, and they were permanently rescued from infertility.

Rosales explained that the mechanism underlying the normalization of HDL function in these animals is set off by a series of biochemical reactions. The process is kick-started by serum opacity factor binding to an HDL molecule which then recruits another HDL particle. This union causes one HDL molecule to dump some of its cholesterol into the other HDL molecule, making one HDL lipid-rich and the other lipid poor. As this process continues, the lipid-rich HDL gets bigger, hungrier for more cholesterol and accumulates proteins with address tags to the liver. When these proteins then bind to their receptors in the liver, the lipid-rich HDL molecule gets cleared, reducing cholesterol and restoring fertility.

Based on their promising preclinical results, the researchers plan to conduct a clinical study to investigate lipid levels in women undergoing treatments for idiopathic infertility. If these patients have high HDL levels, serum opacity factor may be a line of future treatment.

“Even if we were to help 1% of women who are struggling to conceive, it would be life-changing for them, and I think that's where we can make the most impact with our research,” said Rosales.

This article was first published by Houston Methodist. Read the original.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

E-cigarettes drive irreversible lung damage via free radicals

E-cigarettes are often thought to be safer because they lack many of the carcinogens found in tobacco cigarettes. However, scientists recently found that exposure to e-cigarette vapor can cause severe, irreversible lung damage.

Using DNA barcodes to capture local biodiversity

Undergraduate at the University of California, Santa Barbara, leads citizen science initiative to engage the public in DNA barcoding to catalog local biodiversity, fostering community involvement in science.

Targeting Toxoplasma parasites and their protein accomplices

Researchers identify that a Toxoplasma gondii enzyme drives parasite's survival. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Scavenger protein receptor aids the transport of lipoproteins

Scientists elucidated how two major splice variants of scavenger receptors affect cellular localization in endothelial cells. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Fat cells are a culprit in osteoporosis

Scientists reveal that lipid transfer from bone marrow adipocytes to osteoblasts impairs bone formation by downregulating osteogenic proteins and inducing ferroptosis. Read more about this recent study from the Journal of Lipid Research.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.