Back to the (poly)basics

Glycerolipid synthesis occurs largely in the endoplasmic reticulum, or ER. Almost all the enzymes involved in making glycerolipids are embedded in the membranes of the ER. The exception is a family of enzymes called lipins, which dephosphorylate phosphatidic acid, or PA, to generate diacylglycerol in the penultimate step of glycerolipid synthesis.

Lipins are soluble proteins that can be found in the cell cytosol but can move to the ER membrane to perform their function. This family of enzymes consists of three members known as lipins 1-3. Genetic studies have shown that increased levels of lipin 1 in the fat tissue of transgenic mice can improve glucose homeostasis, and genetic mutations in human lipins 1 and 2 have been associated with diseases such as rhabdomyolysis, a rapid destruction of skeletal muscle cells, and Majeed syndrome, a rare condition characterized by recurrent episodes of fever and inflammation in the bones and skin. At the molecular level, a series of studies has demonstrated a complex regulation of the lipin family that is tied intimately to their phosphorylation state and the chemical properties of PA (1-4).

The substrate of lipins can exist in two electrostatic forms: it is either monoanionic (-1 charged) or dianionic (-2 charged) (5). When the membrane pH rises or when PA is in proximity to hydrogen bond donors — such as phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) — it exists as a dianionic compound. All lipin family members preferentially associate with dianionic PA; this can be observed as an increase in lipin activity and association with PA in the presence of PE (2-5). And while it has been known that the lipins are highly phosphorylated, it is now becoming clear how phosphorylation might affect lipin enzymatic activity (2-4). Specifically, phosphorylation negatively regulates the ability of lipin 1 to associate with, and act against, dianionic PA (2). However, the activities of lipins 2 and 3 are not affected by their phosphorylation state (3, 4). Why such a stark difference in molecular regulation of enzymes that catalyze the same reaction? Perhaps the answer lies within lipins themselves.

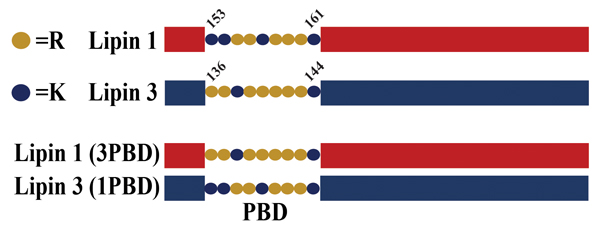

A schematic of lipin polybasic domain exchange mutants. Salome Baroda/University of Virginia

A schematic of lipin polybasic domain exchange mutants. Salome Baroda/University of Virginia

All lipins contain a polybasic domain, or PBD, a short nine-amino acid sequence composed of lysines and arginines that is responsible for lipin association with PA (6). The precise sequence and number of lysines versus arginines varies between the lipins. Recent work has revealed that the unique PBD of lipin 1 may be the reason it is subject to regulation by its phosphorylation (phosphoregulation) (4). The evidence for this came from studies where the lipin 1 PBD was replaced with the PBD from lipin 3. When the activity of this mutant lipin was measured, it was found that the presence of the lipin 3 PBD eliminated the phosphoregulation of the lipin 1 enzyme.

Conversely, the specific activity of the lipin 3 mutant containing the lipin 1 PBD showed potent inhibition by phosphorylation. While it is possible that the mutant lipin proteins became dysregulated, phosphoproteomic analysis found no significant changes compared to their wild-type counterparts.

To date, there is no structural information available for lipins. As such, the mechanisms whereby lipin 1 phosphorylation interferes with the ability of the lipin 1 PBD to recognize dianionic PA are a matter of speculation. However, the variation in the molecular regulation of lipins suggests that each has a unique role in specific cellular stimuli and physiological conditions, and perhaps the field is just beginning to elucidate the true complexity behind the function of these enzymes. Further work is needed to probe exactly how these enzymes may be regulated post-translationally. In particular, the exact residues and molecular pathways involved in the negative phosphoregulation of lipin 1 are still unknown and could provide insight into its physiological role.

References

1. Harris, T.E. et al. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 277-286 (2007).

2. Eaton, J.M. et al. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 9933-9945 (2013).

3. Eaton, J.M. et al. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 18055-18066 (2014).

4. Boroda, S. et al. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 20481-20493 (2017).

5. Shin, J.J. & Loewen, C.J. BMC Biol. 9, 85-7007-9-85 (2011).

6. Ren, H., et al. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21, 3171-3181 (2010).

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.

Lipid-lowering therapies could help treat IBD

Genetic evidence shows that drugs that reduce cholesterol or triglyceride levels can either raise or lower inflammatory bowel disease risk by altering gut microbes and immune signaling.

Key regulator of cholesterol protects against Alzheimer’s disease

A new study identifies oxysterol-binding protein-related protein 6 as a central controller of brain cholesterol balance, with protective effects against Alzheimer’s-related neurodegeneration.