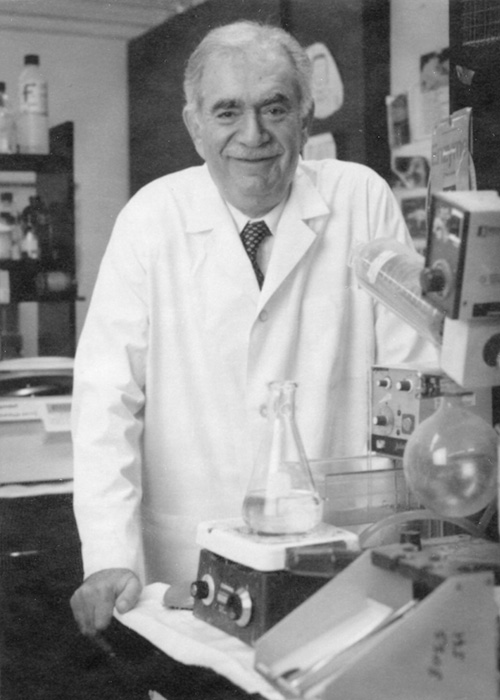

In memoriam: Harry Schachter

Harry Schachter, a leader in the field of glycobiology and glycan synthesis, died April 17 at the age of 91. He was a member of the American Society of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology since 1970 and served on the Journal of Biological Chemistry editorial board in 1983.

Schachter was born on Feb. 25, 1933, in Vienna, Austria, to Miriam Schachter Albright and Usher Schachter. In 1938, his family moved to Port of Spain, Trinidad, to escape Nazi persecution. When he was a student at St. Mary’s College, Schachter won the top prize in Trinidad for the Cambridge Advanced Level Examinations and earned the Jerningham Gold Medal.

In 1951, the family immigrated to Toronto, Canada. Schachter earned his B.S., M.D. and Ph.D. in biochemistry at the University of Toronto. He did his postdoctoral work at Johns Hopkins University and then returned to Canada in 1968. He became a professor and chair for the biochemistry department at the University of Toronto and chaired the Division of Biochemical Research at the Hospital for Sick Children.

Schachter’s research focused on the activity of glycotransferases, enzymes that mediate the glycosylation or linkage of sugars to accepter substrates. He characterized the glycosylation pathway for N- and O-linked glycans and determined the branching sequence of N-glycans found on secreted proteins and cell surface receptors. Schachter also helped characterize the first congenital disorder of glycosylation and investigated the roles of glycosylation in other diseases and tissue development.

During his career, Schachter published over 160 papers and edited several books. In addition to serving on the JBC editorial board, he was chief editor for the Glycoconjugate Journal. He earned multiple awards for his contributions to the field, including the Rosalind Kornfeld Award for Lifetime Achievement in Glycobiology in 2010 and the Austrian Cross of Honour for Science and Art First Class in 2011, and he was an elected fellow of the Royal Society of Canada.

Schachter’s colleagues and friends appreciated his kindness and good humor. The authors of an obituary in the journal Glycobiology wrote, “His visions and leadership, with humor and laughter, were ‘infectious’ and stimulated the interest of students and colleagues.” Schachter had a passion for music and enjoyed singing for family, friends and residents of a local senior center. His YouTube channel showcases a variety of performances, from Yiddish songs passed down by his father to popular classics by Frank Sinatra.

Schacter is survived by his wife, Judy; children, Asher and Aviva; and grandchildren, Adam, Noah, Sarah, and Audrey.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Simcox wins SACNAS mentorship award

She was recognized for her sustained excellence in mentorship and was honored at SACNAS’ 2025 National Conference.

From humble beginnings to unlocking lysosomal secrets

Monther Abu–Remaileh will receive the ASBMB’s 2026 Walter A. Shaw Young Investigator Award in Lipid Research at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

Chemistry meets biology to thwart parasites

Margaret Phillips will receive the Alice and C. C. Wang Award in Molecular Parasitology at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10 in Washington, D.C.

ASBMB announces 2026 JBC/Tabor awardees

The seven awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2025 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Decoding how bacteria flip host’s molecular switches

Kim Orth will receive the Earl and Thressa Stadtman Distinguished Scientists Award at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Thiam elected to EMBO

He was recognized during the EMBO Members’ Meeting in Heidelberg, Germany, in October.