Daniel N. Hebert (1962–2024)

When the news spread that Dan Hebert died on Dec. 8, 2024, many colleagues cried. We lost a dear friend and so much more: a true scholar, a colleague and a caring mentor. But above all, a warm friend.

Scientifically speaking, Dan’s passion for applying rigorous biochemical experiments to complex cell biological problems was evident early in his career. Dan did his doctoral training with Tony Carruthers at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, obtaining his Ph.D. in 1991. His careful analysis of the oligomeric state of the erythrocyte glucose transporter has stood the test of time. His doctoral training prepared him for his seminal postdoctoral work at the Yale University School of Medicine with Ari Helenius. Through painstaking reconstitutions of secretory protein passage through the endoplasmic reticulum, or ER, Dan was able to map the steps in folding and assembly of complex membrane proteins such as influenza virus hemagglutinin. This work has become the stuff of textbooks such as Molecular Biology of the Cell. It revealed in detail the coupling of protein N-glycosylation, engagement of the lectin chaperones calnexin and calreticulin, disulfide-bond formation and trimerization of this large protein and established an array of tools that could be deployed to accurately follow protein maturation in the cell.

Knowing Dan well, wherever he is now, we imagine him laughing, with a beer in his hand, looking at the four of us writing his obituary. With his humor, Dan would probably start by saying that he used the time spent at Yale soaking up the opportunity to learn from a giant in Helenius, and from there he was inspired to dig and dig to explore in depth the fascinating machineries that regulate protein folding and quality control in the ER of our cells.

In the lab

In his independent research as a faculty member in the biochemistry and molecular biology department at UMass Amherst, the scientific activity of Dan Hebert and his wonderful team was centered on sugars, proteins and their cross talk. A large fraction of the eukaryotic proteome traverses the ER to be secreted from the cell or incorporated into cellular membranes. Most of these proteins are glycosylated at asparagine residues (N in single letter code and hence N-glycosylation). The Hebert lab delivered essential insights into the roles of the highly hydrophilic N-linked glycans composed of two N-acetylglucosamines, nine mannoses and three glucose residues, showing that they do not simply increase the solubility of immature polypeptides in the crowded ER environment. Rather, these sweet appendices are processed by ER-resident glucosidases and glucosyltransferases that remove and add back a glucose to retain immature polypeptides in the chaperone-rich ER environment, thus favor their proper folding program.

Dan and his team described these mechanisms in molecular details and went on to give essential support to models showing that the cellular protein factory uses slow removal of mannose residues to establish when a polypeptide, for one reason or another, is spending too much time in the folding compartment. If a protein fails to become native, it must be removed to give room for the newly synthesized polypeptide chains that continuously enter the folding compartment. Elegantly, old proteins have fewer mannose residues on their N-linked glycans than proteins that just entered the compartment; the older proteins are selected for retro-translocation into the cytoplasm where they are degraded by the ubiquitin proteasome system.

The Hebert lab essentially uncovered the molecular mechanisms by which N-linked glycans act as reporters and handles for region-specific recruitment of molecular chaperones, enzymes and other quality control sorting factors: the glycan code. This code guides the folding, maturation and quality control of the maturing polypeptide in the ER. Over the years, Dan’s work delved ever more deeply into these questions, and he left no stone unturned to understand the principles that mediate recognition by the two quality control glucosidases in the calnexin cycle, UDP-glucose:glycoprotein glucosyl transferases 1 and 2, known as UGGT1 and UGGT2 — their differences and mechanisms of action.

Before Dan’s work, few scientists appreciated the role of N-glycosylation in secretory protein folding and quality control. Researchers considered N-glycosylation one of the posttranslational modifications, but this is misleading because the lion’s share of N-glycosylation in metazoans occurs cotranslationally, when the nascent unfolded polypeptide is translocated into the ER lumen. The cotranslational addition of N-glycans in higher eukaryotes positions these modifications upstream in protein biosynthesis, to aid with early maturation and quality control events governed by, among others, the lectin chaperones calnexin and calreticulin, which recognize specific oligosaccharide structures along with the ER folding gatekeeper, UGGT.

Throughout his work, Hebert had a keen eye for disease relevance, and he contributed substantively to the current understanding of how the processing on N-linked oligosaccharides regulates the retention in the folding ER environment of immature proteins, the selection of native polypeptides for secretion and the targeting of terminally misfolded proteins for dislocation into the cytoplasm for proteasomal degradation. Researchers have now widely accepted that the defective function of these fundamental steps in the ER underlies diabetes, genetic lung disorders, liver cirrhosis, Alzheimer’s and many other protein-folding diseases.

Dan dreamed of elucidating the journey of a secretory protein from its entry into the ER through the translocon to its arrival in a mature, functional state at its proper destination. He wished to relate the ER machinery that relies so heavily on the N-glycan-structure code to fundamental steps in client folding, as researchers have studied in great detail in laboratory purified systems. He appreciated better than most that these processes would incorporate regulatory aspects, organizational impact and specific recognition using both structural and sequence information. He knew and loved the fact that physicochemical principles would shape protein folding landscapes that underlie these complex cellular events. His rigorous experimental strategies laid the groundwork for these dreams to be fulfilled.

Beyond the lab

Dan passed his passion for science, devotion to critical thinking and strict interpretation of well-designed experiments on to his trainees who were fortunate to have such a caring and disciplined mentor guiding their early careers. Many have gone on to influential positions in biotech and pharma industries or academia and government. They carry the torch that Dan passed to them. They also cared deeply about him — all their interactions were imbued with his warmth and humor.

As we cope with the loss of this impactful scholar and true friend, we remember the beers shared around the world after never-ending evening sessions of meetings; the sarcasm; the fights about politics and Roger Federer; the lobsters at Cold Spring Harbor; stories about our children; and lots of emails where science was always mixed with humor, jokes and at least one sentence that showed genuine interest in our well-being, family and life outside the lab.

Dan loved sports. An avid tennis player through college and beyond, he also was loyal and attached to all Boston teams, whatever their level of performance at any given time. As a fan of Roger Federer, whom Dan described as “elegant as the calnexin cycle,” his email exchanges with one of us peaked during Grand Slam matches, especially Wimbledon, Roger’s garden.

It was easy to underestimate Dan — always good natured and stress-free, always finding time for people. Already as a postdoc, he skillfully mastered (and limited) his working hours, which made many wonder how good and dedicated a scientist he was … Until the data poured in, and his papers were accepted in top journals. Then doubt changed into desire, a desire to learn how he did it.

Dan did not find a good work–life balance, he was work–life balance. He had it down: doing the science he loved and doing it excellently, while spending enough time with family and friends, all the while being a great mentor and caring for everyone in his lab. The "how are you" question was always answered with a smile and never with the common response of "busy." Dan had many an admirer for his life artistry.

Colleagues who had the good fortune to rub shoulders with Dan, whether at UMass Amherst or scientific meetings, knew the respect, humor and joy he graced everyone with, whether at the bar, discussing posters at a conference or on walks up New Hampshire mountains. He linked his passion for his science with his bonds with scientists, establishing enduring friendships. To arrive at Dan and Leah Hebert's home was always to experience a warm embrace. Every stay recharged visitors from the day-to-day.

Dan's death came as a shock to many; only few colleagues knew how ill he was. Science was his safe haven and distraction. Giving up was not written in his book. He talked about “one more chemo and then a break to recover.” He continued working and sharing his life with family and friends as if he were healthy. He remained productive and dedicated to advising his trainees in the last seven years, while undergoing chemotherapy. He kept doing science at the highest level and remained "Dan" in every sense.

Dan was sustained and grounded by his deep love for his family. He is survived by his wife of 33 years, Leah (Kelley) Hebert; their son, Dylan, of Oxford, England; and daughter, Shannon, of Boston, Massachusetts. He was very proud of his children, spending many moments throughout the day connecting with them, no matter their location (Dylan has lived in many places around the globe).

Dan’s family and colleagues have established a graduate scholarship award in his memory.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Summer research spotlight

The 2025 Undergraduate Research Award recipients share results and insights from their lab experiences.

Pappu wins Provost Research Excellence Award

He was recognized by Washington University for his exemplary research on intrinsically disordered proteins.

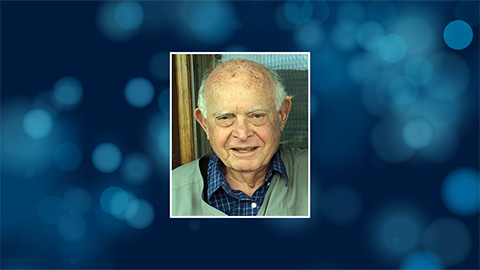

In memoriam: Rodney E. Harrington

He helped clarify how chromatin’s physical properties and DNA structure shift during interactions with proteins that control gene expression and was an ASBMB member for 43 years.

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.