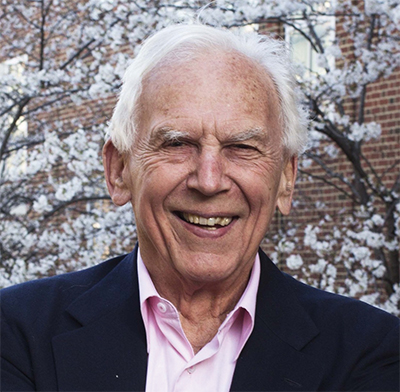

J. Thomas August (1927 — 2019)

J. Thomas August, an early member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology who also served on the editorial board of the Journal of Biological Chemistry, an ASBMB journal, died Feb. 11 of cancer. He was 91.

A pioneer in immunology who worked to find vaccines for Zika, dengue, influenza and other viruses, August led the pharmacology department at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine for 23 years. Under his tenure, the department shifted its focus to molecular biology and virology.

Tom August arrived at Johns Hopkins in 1976 as director of what was then called the department of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. In 2006, he and a colleague founded Immunomic Therapeutics Inc., which nine years later entered a licensing agreement with a Japanese firm for its LAMP technology. At the time of August’s death, the $300 million upfront payment was the university’s largest technology transfer.JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

Tom August arrived at Johns Hopkins in 1976 as director of what was then called the department of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. In 2006, he and a colleague founded Immunomic Therapeutics Inc., which nine years later entered a licensing agreement with a Japanese firm for its LAMP technology. At the time of August’s death, the $300 million upfront payment was the university’s largest technology transfer.JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY

In 1980, August changed the field of immunology with the discovery of lysosome-associated membrane proteins, or LAMPs, which help activate the immune system.

August was born in Whittier, California, in 1927, the youngest of six children. He served in the Army, stationed in Alaska, late in World War II. He graduated in 1954 from Stanford University School of Medicine and did additional training at the University of Edinburgh and Harvard Medical School.

Before moving to Hopkins in 1976, he held faculty positions at Stanford, New York University and Albert Einstein College of Medicine. He was a scientist and board member at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in the 1960s and worked with researchers at the California Institute of Technology, the Salk Institute, Oxford University, Uppsala University in Sweden, Perdana University in Malaysia and Johns Hopkins Singapore.

After August’s death, the Perdana University School of Data Sciences named its inaugural symposium for postgraduates and young researchers in his memory.

Asif M. Khan, the school’s dean, wrote in a letter to August’s family that the school would not have existed without his foresight, guidance and support. “This is the least we can do to relive his memories and dedication to science, in particular his patience in nurturing early researchers,” Khan wrote.

August held eight patents on vaccine-related technologies, published hundreds of scientific articles, and received many honors. In 2001, he was named a Hopkins university distinguished service professor.

James Stivers, interim director of pharmacology and molecular sciences at Hopkins, stated in a university press release announcing August’s death, “It is hard to exaggerate the personal and scientific impact of Tom on our department. The example he set in terms of pursuing creative and innovative research with direct application to human health was inspiring, and his gracious demeanor and warmth will always be with us.”

August was married for 67 years to Jean Nordstrom August, whom he met in high school. He is survived by his wife, three children, five grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

I met Tom August as a second-year medical student at the Johns Hopkins University. I had intended to enroll in an M.D.–Ph.D. program, with my research to be undertaken in the history of medicine, but that endeavor was not working out, and Tom offered me a training grant–funded place in his department as a graduate student in the late Mette Strand’s laboratory, which was closely allied and in the same spaces as his own. Tom was a mentor and friend throughout my years as a graduate student, when I returned to the hospital as a medical student and house officer, and when I joined the faculty in the department of medicine.

What strikes me in my memories of Tom is his unique combination of energy, enthusiasm, supreme powers of concentration and the joy he experienced in so many spheres of life. Tom was truly excited by everything he chose to do, whether in the laboratory or in his garden, and he tackled every task and difficulty as if it were a great adventure. By the time he arrived in the laboratory in the morning, he had already been up working in his garden from the early dawn. He worked on prodigious planting programs, completely transforming the environment around the house that he and Jean had built on a beautiful hillside. In what he considered a major coup, Tom had arranged with the local tree surgeons and landscapers to deposit on his driveway extensive piles of the wood chips they would have otherwise had to truck to the landfill. He used the wood chips as mulch without any other fertilizer and with impressive results.

In the laboratory, he was incisive and forthright. He could sit undisturbed and concentrate on a manuscript despite the roar of vacuum pumps, the chatter of graduate students and postdocs, and the incessant ringing of the telephone. And he brought the same concentration to bear on questions brought to him by his students.

Tom was a mentor who was deeply concerned about guiding the development of students and postdoctoral fellows. His guidance was very valuable. And he warmly welcomed students, staff and faculty associated with him in the department and in his lab to periodic gatherings on the spacious deck at home; the Baltimore-style crab feasts were particularly memorable.

Tom was accessible and open. He had a chairman’s-style office with a private bathroom and shower. At one point, somehow, a large white rabbit started living in the office, until he had to be rehomed because of a habit of chewing on the wiring.

Around Christmastime, Tom would prepare a large punch bowl of egg nog, and everyone in the department stopped by to enjoy the holiday season with him.

—William S. Aronstein

Vice President, Medical Affairs

CTI Clinical Trial & Consulting Services

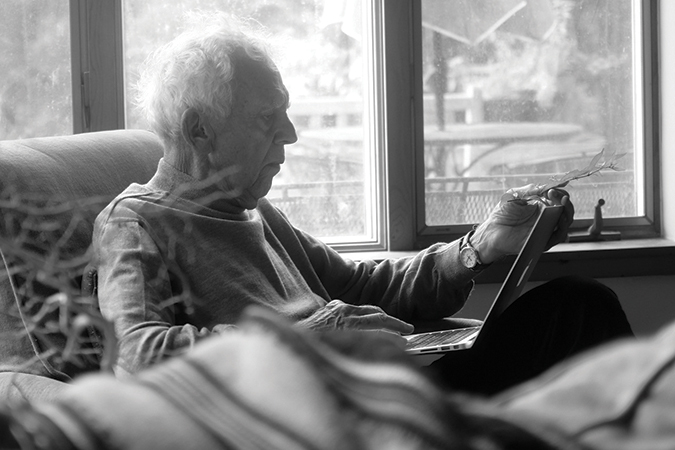

Tom August works at the family’s Martha’s Vineyard summer house in August 2018. August loved his garden there, on which he spent many hours every day. He also loved their holiday apartment in Lille, France, and was a great Francophile.PAUL NORDSTROM AUGUST

Tom August works at the family’s Martha’s Vineyard summer house in August 2018. August loved his garden there, on which he spent many hours every day. He also loved their holiday apartment in Lille, France, and was a great Francophile.PAUL NORDSTROM AUGUST

There are so many remarkable aspects in Tom’s life as a person and as a scientist that it is difficult to select witch one had the most impact. However, I choose to highlight the one that I think has the most bragging rights. Tom could truthfully say that the sun never sets in his laboratory, but he never said that.

I first meet J. Thomas August during my application to the graduate program in pharmacology and molecular sciences program at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. At that time, Tom was the chairmen of the department. I later joined the laboratory of Mette Strand, one of Tom’s former student. Mette was a good friend of Tom, and both laboratories were close. The department faced together difficult moments during that period, such as a very tragic death of a student and the sudden death of Mette. However, these events had great effects in strengthening the bonds and the friendships within the department.

After I graduated, I joined Tom’s laboratory to work on vaccines. At that time, Tom was stepping down as the department chair and started to focus 100% of his time on research. Tom had this great sense of wonder and enthusiasm for everything in life, but nothing could bring him more joy then to see new data and engage in a long scientific debate. His joy was infectious, and we all felt very motivated and energetic after those conversations.

In a space of two years after I joined his laboratory, Tom was awarded several NIH grants, including an R21, R01/R37, U19, and a NO1, and started a brand-new laboratory at the Johns Hopkins Singapore. I had two projects; one was to develop a DNA vaccine for dengue and the other for HIV. Both projects used the lysosomal targeting system to enhance antigen presentation to T-helper cells. At that time, we did not know about several requirements for trafficking and enhancement of the immune responses, but the early successes designing the chimeric antigens with membrane protein antigens and lysosomal targeting signal were very important to makes us confident about the system and persist in furthering our understanding of the system. One particular challenge that helped us was the targeting of the p55 Gag antigen, the capsid protein of HIV-1. During our attempts to make the Gag protein traffic, we discovered that the luminal portion of the lysosomal associated membrane protein, or LAMP, played a prominent role on protein trafficking and that it could tremendously increase total protein expression (1).

As we moved forward with the development of our vaccine candidates, we learned how much politics is involved in field of vaccines against infectious diseases. I am not referring to the academic politics but to national and supra-national politics. Vaccines are major public health tools, and their use is mostly under the control of governments and public opinions. If that is not enough, the business model and economic viability of vaccines are extremely complicated. All the biomedical scientific knowledge of the world is not enough to make a vaccine. It need much more than that. As these challenges were being unveiled to us, we gradually understood the need to work locally all over the world. So, in addition to the need to understand the molecular diversity of the pathogens and the immune responses of the population in endemic areas, we would also need to understand the politics of public health and research institutions of endemic countries.

In response to this, Tom expand his laboratory work from Baltimore to Singapore, Brazil and Denmark, and worked in collaboration with local institutions in several countries in all continents. In order for all sites to be able to participate in our weekly meetings, the meetings were held in the very early morning or late evening in order to accommodate the up to 12 hours’ time difference. When the day was starting in Baltimore, the day was ending in Singapore and vice versa. Thanks to Paul August, Tom’s son, we are pioneers in using all the new IP-based video conferencing systems and internet-based project management technologies that were coming up in the late 90s and early 00s. We used several beta versions of Skype, Bootcamp and other tools. In addition, there was a constant flow of students, postdocs and researchers among the laboratories. It was truly a melting pot of quite different cultures. Tom had created an extremely creative environment that would be the envy of all Silicon Valley startups today.

As Tom’s age advanced, he became more anxious and determined to see the final product of his life work. His obsession, in his own words. was that he wanted to “make something useful” before he died. In his view, useful was something tangible like a vaccine implemented in a national immunization program. His point was that research is supported by taxpayers, and scientists have the duty to bring the benefits of the research to society. For him it was not an issue of basic versus applied research or Einstein versus Thomas Edison. From his perspective, academia needed to play a role in transition that is not necessarily covered by the pharmaceutical industry.

I remember Tom and Mette mentioning many times that we needed to determine a practical goal in our projects and then address fundamental biological questions to overcome the obstacles along the way. The most cherished lessons I learned working with Tom were (1) that time is the most valuable resource, (2) that science serves society and (3) that scientists must enjoy science as much as life.

Tom August met his wife, Jean, when they were both in high school. They were married for 67 years.Dan laneAt the end of each day we would sit with Tom in his office to talk about what we had done, new experimental data or an article we read. We would sit by his desk, which was the desk of John Jacob Abel (the founder of the pharmacology department) or on an antique dentist chair. Along the peripatetic discussions, Tom would share a lot of fun stories like driving a convertible Alfa Romeo with a goat wearing sunglasses siting by his side, or the day during his medical residency at Stanford that he attended Marilyn Monroe with a pneumonia she got after performing a show in Korea wearing only what he described as the famous mink bikini, or stories about a rabbit he had in his office that was trained to use the bathroom. One could create a surreal image of some student being interviewed by Tom in his office, sitting in a dentist chair with the rabbit hopping around.

Tom August met his wife, Jean, when they were both in high school. They were married for 67 years.Dan laneAt the end of each day we would sit with Tom in his office to talk about what we had done, new experimental data or an article we read. We would sit by his desk, which was the desk of John Jacob Abel (the founder of the pharmacology department) or on an antique dentist chair. Along the peripatetic discussions, Tom would share a lot of fun stories like driving a convertible Alfa Romeo with a goat wearing sunglasses siting by his side, or the day during his medical residency at Stanford that he attended Marilyn Monroe with a pneumonia she got after performing a show in Korea wearing only what he described as the famous mink bikini, or stories about a rabbit he had in his office that was trained to use the bathroom. One could create a surreal image of some student being interviewed by Tom in his office, sitting in a dentist chair with the rabbit hopping around.

I have one story of Tom of my own. One time returning from Brazil with Tom, before going to Fiocruz, Tom stopped in my parents’ home to say goodbye, and my father give him a couple of beautiful ripe rose mangos he’d collected by hand from a tree at his backyard. From Fiocruz, we went directly to the airport, and Tom decided to eat the mango on the plane. No one knows how delicious a rose mango smells until they have cut one open at 30,000 feet. The intense mango aroma impregnated the entire plane cabin. I had never imagined that the air pressure of a plane would enhance the mango smell so much. We ate the mango quickly before the flight attendant found us. When she arrived, she did not complain but said in a funny way, “I know what you did.” And then Tom opened his bag and showed a beautiful large, perfectly ripe guava fruit that my father had also given to him. The flight attendant then said, “OK, you can have it but you must give me half.” We had a big laugh. Then we shared the guava at 30,000 feet with the flight attendant. It was a delicious experience.

Although Tom did not see with his own eyes a vaccine using his technology being implemented in an immunization program, he got pretty close to it. We may see it in a few more years. Nevertheless, from the global health point of view he saw many useful things he did. Thanks to him Fiocruz–Pernambuco has a virology department today. Most of the faculty of the department worked with Tom, including myself, Rafael Dhalia, Eduardo Nascimento, Marli Tenorio, Carlos Brito, Ulisses Braga, Patricia Furtado, Ihid Leao, Luciana Arruda, Romulo Maciel, Andre Furtado, Alberto Duarte and many others. The virology department at Fiocruz played an essential role on the discovery of the outbreak of a new disease in Northeast Brazil, determining that this new disease was caused by the Zika virus, that the Zika virus could invade the central nervous system and that the Zika virus was the cause of the microcephaly outbreak that followed.

I am convinced that Tom will see from where he is a Zika vaccine using the LAMP technology and will be very proud of us.

—Ernesto T. A. Marques

Associate Professor, Department of Infectious Diseases and Microbiology, University of Pittsburgh

Public Health Scientist, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Instituto Aggeu Magalhães, Pernambuco Brazil

1. Marques, E.T. Jr. et al. J Biol Chem. 278(39), 37926-36 (2003).

Tom’s career was distinguished by major scientific and professional accomplishments, but the memories I treasure most are those of his irrepressible enthusiasm for just about everything, his insatiable curiosity — especially about science and the satisfaction that spilled over from time spent in his yard planting, splitting logs, spreading wood chip mulch, enjoying the pond and its critters, and sharing it all with neighbors and friends.

I still have rhubarb and a black turkey fig tree that Tom and Jean moved from their yard to ours over 30 years ago, and I will always remember the arms-full bouquets of flowers Tom brought in and distributed around the department from spring to fall each year.

—Wade Gibson

Professor Emeritus,

Johns Hopkins Department of Pharmacology

and Molecular Sciences

I’ve known Tom August for over 50 years — first as a summer student when I was in college and then as an M.D.–Ph.D. student. (As a measure of his influence, I’ve always considered myself to be a Ph.D.–M.D. and not the other way around.) He was my teacher, mentor, supporter, source of inspiration and dear, dear friend for my entire adult life.

Although I started my training planning to be a molecular biologist and I loved my years in research, I ended up as a clinical neonatologist in a world that revolves around putting tubes into babies' tracheas and tiny blood vessels, turning knobs on mechanical ventilators, staring at X-rays and blood gases, and talking with parents. While Tom’s importance to me and his influence on my life is every bit as important today as it has been for the past 50 years, it’s all been on a personal level, and I will leave it to others to try to capture and comment on the vast scope of Tom's scientific contributions. That said, seeing his career from a professional distance, what has always impressed me is that Tom didn't just know how to study a problem; he knew what to study.

Tom was an enthusiast ... about everything! When I was working as a summer student, he shared a book that he had found in the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Library called “The Behavior of the Lower Microorganisms” by H.S. Jennings published in 1906. We had endless discussions around how the molecular biology of the behavior of an organism could be analyzed, and those discussions ultimately led to my thesis work on the phototactic response of the eukaryotic green algae Chlamydomonas.

Tom was equally enthusiastic off the academic grid. I introduced him to an architect-friend, and soon we were rebuilding a tiny "potting shed" next to Tom and Jean's home to make it into a guest house. Ignoring the principle of not letting the perfect be the enemy of the good, the design called for taking about 8 inches off one side of a 4-foot long/7-foot high/2-foot thick brick wall and adding the bricks to the other side. Together and with great vigor, we hacked away at the brick for a few days and laid the bricks on the other side a few days later (developing a modicum of skills along the way). Whether it was swimming in Cold Spring Harbor at midnight in December or manning the bilge pump through the night on my family's sailboat (long story), Tom was in.

A few weeks before he died, Tom was talking about his hope that he would be able to spend some weeks in Lille, France, and get back to Martha's Vineyard over the summer. He said: "I just love living."

—Robert Stavis,

Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania

Rara avis: a rare bird. While it is an accurate tag, the words fly straight from their Latin meaning to perch on higher branches of mental fancy and capture my childhood at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. Rara: rare--rarefied. Avis: bird--free as a bird.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, on the North Shore of Long Island, was, in the 1960s of my childhood, a rare bird. Founded in 1890 on land previously part of the Cold Spring Whaling Company and given by John Jones, the lab had, in the 60 years since, grown with the evolving science of genetics, morphed into an institution for qualitative biology, and recombined the two during a heady era of important progress in molecular biology, cytogenetics, and DNA and tumor virus research. Summers, the lab offered seminars and courses to which scientists came from many corners of the globe. What made Cold Spring Harbor special was the way it allowed them to work, play, eat and talk together in a summer-camp-for-adults’ casualness. The scientists could bring their spouses and children with them. And what a summer that gave to their children.

Even into the early 1970s the lab was still a wild bird, untamed, ungroomed, even a little flighty. Its wildness, its flightiness, must have allowed for a certain kind of intellectual freedom and scientific risk-taking, the mood of which permeated every aspect of life there. We tried making maple syrup in a big kettle over an outdoor fire and foraged for a wild dinner when we dined on clams, eels, wild greens and roasted day lily tubers and drank homemade birch bark beer. For many years snowy winter days brought the chance to ski on a short run cleared on lab grounds — where we were slowly pulled to the top of the hill by a homemade rope tow powered off an old car engine, a collaborative effort with neighbor Jim Eisenman, the local judge.

But those are memories from later years after, in 1967, my family moved to Cold Spring Harbor from Manhattan, first to Osterhout Cottage at the lab and then to a house, a former gardener’s cottage named Merrywich, nearby in Laurel Hollow. Those were off-season activities when all the “summer people” were gone and a small core of scientists, staff, spouses and children remained in 100 acres of Arcadian isolation.

Summertime in the ‘60s, as young children, we roamed barefoot and free as birds, seemingly beholden only to the dining bell that summoned us to meals at Blackford Hall. We gorged on wild wineberries and drank from the spring behind Jones Lab, one of the several small springs that gave the Harbor its name. It was a feast of unstructured time that passed in a blur of dirty feet on paths in the woods and grass-stained knees as we played on the lawn behind Blackford Dining Hall. Freeze tag, croquet, French cricket, statues, red light green light, Mother may I? If it rained, we curled in the heavy oak and leather rockers that were scattered in the Blackford Hall Lounge and played endless games of cards, Battleship (the paper and pencil way, charts carefully hand-gridded off and squares filled in with codes signifying one’s fleet), Mille Bornes or Round Robin at the ping pong table. Happy in our Eden, we almost never left the Lab grounds, although we did visit Sagamore Hill more than once over the years — and Craig’s mother took us to see the movie, “The Russians are Coming, the Russians are Coming.” Putting on shoes for these outings was painfully enclosing after weeks of bare feet. One outing that did not require shoes was the occasional multi-family trip to Jones Beach, the beach named for our own Jones of Jones Lab, for a day of surf and plenty of sand on the South Shore of Long Island.

Tom August “tackled every task and difficulty as if it were a great adventure,” according to William Aronstein.COURTESY OF CHRISTINA HECHTBut there was also the rarefied part of life at the lab. Being a middle-class child of the time, I knew them as “Dr. Hershey, Dr. McClintock, Dr. Luria.” “Dr. Crick, Dr. Watson, Dr. Delbrück.” But I recognized them also as Al, Barbara, Salva, Francis, Jim, Max. I saw them in shorts and sandals, we ate together in the dining room, I watched them interact. I knew that lanky Dr. Watson and gentlemanly Dr. Crick had discovered something wonderful called a double helix, but I also knew that a dancing girl (as she was euphemistically explained to me by my father) had jumped out of Dr. Crick’s 50th birthday cake. Dr. Delbrück was Toby and Ludina’s dad and I paddled with Dr. Hershey’s son Peter in a little red rowboat named the Alfred.

Tom August “tackled every task and difficulty as if it were a great adventure,” according to William Aronstein.COURTESY OF CHRISTINA HECHTBut there was also the rarefied part of life at the lab. Being a middle-class child of the time, I knew them as “Dr. Hershey, Dr. McClintock, Dr. Luria.” “Dr. Crick, Dr. Watson, Dr. Delbrück.” But I recognized them also as Al, Barbara, Salva, Francis, Jim, Max. I saw them in shorts and sandals, we ate together in the dining room, I watched them interact. I knew that lanky Dr. Watson and gentlemanly Dr. Crick had discovered something wonderful called a double helix, but I also knew that a dancing girl (as she was euphemistically explained to me by my father) had jumped out of Dr. Crick’s 50th birthday cake. Dr. Delbrück was Toby and Ludina’s dad and I paddled with Dr. Hershey’s son Peter in a little red rowboat named the Alfred.

Most important, I heard them. They talked endlessly (it seemed to me as a child, waiting patiently to ask permission for something) and passionately. Their talk washed over my head, soaked my consciousness in a sea of words. RNA polymerase, DNA replication. E. coli, ribosomes, protein synthesis. They talked at breakfast, at lunch, at dinner. A photo sits here before me: myself aged 7, on the back porch of Blackford Hall, standing beside a picnic table of scientists and holding out a piece of food for a begging dog. Though I did not understand it, I was completely familiar with their language. Bacteriophages, yeasts, media. Messenger RNA, molecular structure. There were also the foreign languages I did not understand yet learned to differentiate as Dutch, Hebrew or Italian, Swedish, German or Japanese. (But in those days, no Russian or Chinese).

The 8:00 dining bell signaled the beginning of each new, limitless day. It summoned us from “the Page motels” and “the cabins;” scented by their wood-paneled walls, furnished with a bare minimum of the plainest furniture. There were less than two dozen motel rooms and four or five cabins, all now long gone and replaced by more elegant structures. A family was given two rooms connected by the bathroom where we scrubbed off poison ivy oil nightly. When the bell started ringing we walked down the steep road past Williams House (whose balcony served perfectly for lobbing water balloons on the parade of nutty costumed scientists in their annual rites at the end of the Phage Course) or trotted and slid down a steep shortcut to land on Bungtown Road, named after the bung — barrel stopper — industry supporting the Cold Spring Harbor whalers who made the village’s fortune in the 1830-60s. From there it was a walk of a few more minutes before we pulled up short at Mr. Dennison’s desk.

Mr. Earl Dennison and his wife ran the dining hall with a crew of teenaged girl assistants. Steel haired, spectacled, apron tied around a sturdy waist: Mr. Dennison was the kind of man to whom you ought to say “Yes, sir” and our main source of summer discipline. One of the Dennisons sat at a little table at the entrance to the dining room with a huge ledger book. Each family had its own set of rows, a line for each member, and as you arrived for a meal you were checked off in the appropriate day’s column. It felt to me as if the length of my line of checks was a badge of honor — or good fortune — representing the number of weeks we spent at the lab every year (some children came only for the length of a weekend seminar or week-long course, while others spent a month or more, returning year after year; we were a summer brotherhood). After Mr. or Mrs. Dennison or Cindy Hotchkiss checked your box, you proceeded more decorously to the cafeteria line where you could choose whatever you wanted! to put on your cafeteria tray. Then, you could eat by yourself, with your family, with a group of other children, or at another family’s table. Freedom, indeed, for an 8-year-old.

[I have often wondered what happened to that ledger book. What a record of scientific history. Baltimore, Berg, Bernheimer, Cairns, Davern, Delbrück, Eagle, Edelman, Fink, Glass, Gunsalus, Hershey, Hotchkiss, Jacob, Kornberg, Marcus, Margolin, Monod, Mulder, Sambrook, Sato, Shapiro, Sharp, Sherman, Speyer, Stahl, Stent, Tissieres, Tomkins, Zetterberg, Zipser: just some of the names that went with the children and adults who made up my summer world. And as I grew older, there were the children for whom I babysat: Delius, Gesteland, Pettersson, Watson and Westphal. Cold Spring Harbor Lab names eight Nobel laureates as having been affiliated with the institution, but I reckon many other past or future Nobelists ate at those dining hall tables and talked over my head as they attended the annual symposium or took a course.]

Some mornings, we children would head to Wawepex Lab for our nature class. Otto Heck reigned as primary instructor, and I felt very daring referring to him (only under my breath to another child) as “O Heck!” We went on expeditions, made collections and labeled them, a small requirement in a summer of few obligations. But I realize now, our lessons gave me an ownership of the natural world by teaching me to know things by sight and by name. They weren’t just “shells”; they were hard-shell clams or soft-shell clams, razor shells or lady’s slippers. The 100 acres of woods that surrounded the lab buildings grew full of individual trees I could call pin oak, white oak, red oak, poplar, sugarbush, black birch (we loved to break off a twig, strip the bark and inhale the scent of wintergreen as an afternoon pick-me-up), the maples and all the pines.

But perhaps the more extraordinary science classes were the passing moments with Nobel-quality minds. I have vivid memories of Barbara McClintock, to a child a small woman dressed always in worn man’s chinos, plaid shirt and brogues, close-cropped hair framing an entirely wrinkled face. She would stop me by the roadside to show me the evidence of plant genetics in the weeds that grew rampant back when the lab was, for me, a wonderland of nature in its unmanicured and quirky state. What was it Dr. McClintock told me about the maroon petals in the middle of the white Queen Anne’s lace? And something even harder for me to grasp about corn? At the time, I knew her only as a kindly and gentle older woman. I did not realize that I was being taught, being paid attention to, by one of America’s foremost women of science, who used studies of maize to discover how genes regulate each other.

My father worked in Jones Lab, the oldest of the labs on the grounds having been built in 1893. Sometimes I would go to find him in the hipped-roofed, high-ceilinged building by the seawall of the inner harbor. He would put me to work at a central worktable, sorting fragile glass pipettes by size. I thought my father so talented, the way he could use his mouth to suck a slender pipette full of some mysterious fluid, quickly slip his thumb-pad over the top, and then with a delicate lifting of his thumb let it back out, single drop by single drop into rows of petri dishes or glass test tubes upright in racks. I asked him recently, what he had been working on back then. The answer: RNA bacteriophages and, later, tumor viruses.

The dining bell rang at noon for another check-in with a Dennison and with one’s parents. Lunch was a sandwich or a bowl of soup or one of the array of salads composed by the dining hall staff. Later, as a teenager, I had a job as one of those dining hall girls. We spent the mornings laughing while we cut radish roses and carrot tulips, mixed up tuna and egg salads and composed those plates with a bit of this and a dollop of that, cutting sheet cakes into squares and placing bowls of quivering Jello cubes on ice beds in the long cafeteria counters. You had time for a swim break in the afternoon before coming back on duty for dinner. As a small girl, those cafeteria girls who lived dorm-style in the top floor of Hooper House, who smoked cigarettes and owned packages of Lifesavers candies and wore their blouse-tails tied in a knot at their waists, represented to me the intriguing mystery of almost-grown-up females.

It was a long, hot one-half mile walk to the beach at the other end of the lab grounds, making for the occasional patch of melted tar, burning hot on bare feet but a squishy, silken, welcome contrast to the rough macadam of Bungtown Road. Three non-Lab families also lived on Bungtown Road and one was that of the lyricist and playwright Arnold Sundgaard. I liked another creation of Mr. Sundgaard’s: He had filled in a marshy area of his sea-edged garden with hundreds of editions of the New York Times and then planted it with what grew into a yellow sea of waving daffodils.

The beach was the preserve of the mothers and children. A small black-and-white photo captures my father, white-skinned from working indoors in his lab all summer, dripping and grinning after a rare quick dip. Experiments run around the clock, so a beauty of Cold Spring Harbor for scientists is the easy access to their laboratories. But while they worked, we children whiled away hours on the beach, in the days when no one worried about sun exposure. We prided ourselves on the increasing toughness of our feet, needed if you were to run freely on the rocky beach. Our mothers sat in a row, talking to each other, I suppose, but what they did was of little concern to us with the whole huge curve of the sandspit that divides the inner and outer harbors, the raft, sand, stones, shells and dried-out tubules from beach grass at our disposal for whatever it was we did, in and out of the salt water.

At 6:00 the dining bell rang one last time. Dinner was a convivial time, and afterwards, scientist Eddie Goldberg was our Pied Piper. I spent many happy evenings in a group of children, clustered on a log in a dirt parking lot, woods on one side, the motels up the hill, a dusty area now the site of the Beckman Lab complex, singing “Sipping Cider Through a Straw,” “Green Grow the Rushes O,” “Hush Little Baby,” and many more he taught us, accompanying with his guitar and tenor voice.

Some evenings were special events: the banquet (lobster and steak with the dining hall girls as waitresses), the picnic (100 people on the lawn of Airslie, at the time home of Lab Director John Cairns, eating hot dogs and hamburgers from Mr. Dennison’s big grill). But for me, the best were the square dances. The dances were held on the large lawn behind Carnegie Dorm (now called Davenport House), the immense Victorian house that fronts on Route 25A at the entrance to the lab. As summer’s late dusk came on, we children would converge on the site, hopping back and forth across the stream on the far edge of the lawn. A fiddler and the caller arrived. Scientists and spouses and URPs (the students of the elite undergraduate research program) and cafeteria workers and year-round staffers arrived, and the dancing began. Do-si-do and allemande left. Swing your partner and promenade home. All you had to do was follow the instructions to dance, free as a bird, on a Long Island summer’s night, clasping hand after hand and swinging in harmony among those rather odd ducks, the scientists.

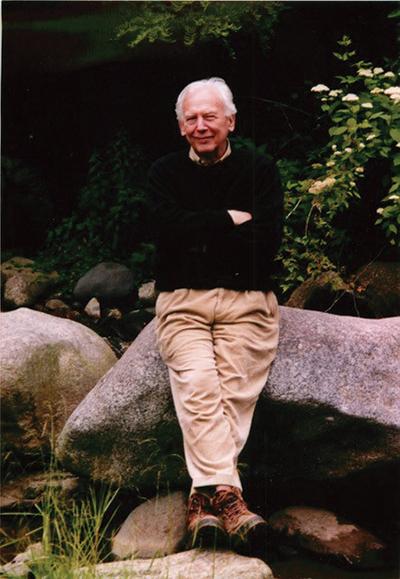

Tom August talks with Johns Hopkins colleague Yadong Wei at his apartment in Baltimore, about a month before his death. August kept working on his latest vaccine development project until the very end. When he could no longer go to his lab, Wei would stop by the apartment a few times each week.PAUL NORDSTROM AUGUST

Tom August talks with Johns Hopkins colleague Yadong Wei at his apartment in Baltimore, about a month before his death. August kept working on his latest vaccine development project until the very end. When he could no longer go to his lab, Wei would stop by the apartment a few times each week.PAUL NORDSTROM AUGUST

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

Women’s History Month: Educating and inspiring generations

Through early classroom experiences, undergraduate education and advanced research training, women leaders are shaping a more inclusive and supportive scientific community.

ASBMB honors Lawrence Tabak with public service award

He will deliver prerecorded remarks at the 2025 ASBMB Annual Meeting in Chicago.

ASBMB names 2025 JBC/Tabor Award winners

The six awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2024 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Daniel N. Hebert (1962–2024)

Daniel Hebert’s colleagues remember the passionate glycobiologistscientist, caring mentor and kind friend.

In memoriam: Daniel N. Hebert

He was a professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who discovered the glycan code that facilitates protein folding, maturation and quality control in the endoplasmic reticulum.