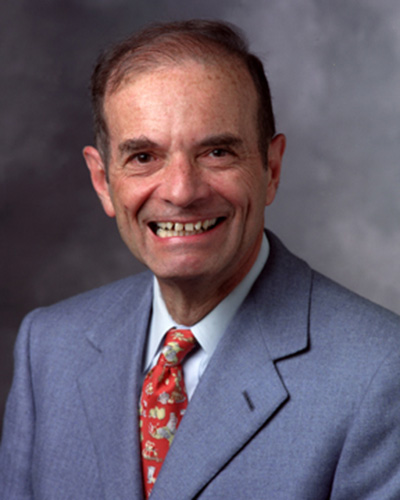

In memoriam: Lubert Stryer

Lubert Stryer, a researcher and author whose work has shaped biochemistry for decades, died April 8 from cancer. He was 86. Stryer was a member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology for 40 years and was known for his pioneering discoveries in fluorescence spectroscopy, human vision and high-speed genetic analysis, and for writing an influential textbook used worldwide.

Stryer was born March 2, 1938, in Tianjin, China, to a German businessman and a Russian refugee. He grew up in Shanghai during World War II and was educated early in life in a one-room school, according to his oral history. In 1948, Stryer and his family immigrated to the U.S.

When he was 16, Stryer began his postsecondary education at the University of Chicago, where he majored in physiology. He spent his summers at Argonne National Lab researching light-sensitive dyes. After graduating from UChicago, Stryer attended Harvard Medical School. He decided on a career in research and then traveled to the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England, to learn about structural biology.

Stryer began his academic career at Stanford University in 1963, where he made significant contributions to the understanding of light signal transduction. He experimentally validated Förster’s theorem, which stated that the efficiency of energy transfer between two light-sensitive molecules depended on the distance between them. His team later showed that this phenomenon could be used to measure the distance between sites on a protein tagged with light-sensitive molecules. These discoveries led to the development of fluorescence resonance energy transfer, or FRET, microscopy an essential, widely used tool of biochemistry that aids in illuminating protein and nucleic acid structures and interactions.

In 1969, Stryer moved to Yale University as a full professor. His research at Yale on the molecular mechanisms of vision, particularly the role of rhodopsin and G protein–coupled receptors, has been foundational to the field. He discovered that each photo-excited rhodopsin molecule activates approximately 500 molecules of another protein, transducin, which amplifies the signal that leads to vision.

In addition to his groundbreaking research, Stryer was an educator and author. His textbook Biochemistry, first published in 1975, is considered one of the most authoritative and comprehensive resources in the field. Translated into multiple languages, the book has been used by students and professionals around the world.

Neelabh Datta, a biochemistry undergraduate student at the University of Calcutta and summer fellow at Stanford, said Stryer’s textbook inspired his love of science and biochemistry.

“The red hardcover edition was more than just a book; it was a gateway to a wonderland where bimolecular complexities were divulged with clarity and wonder,” Datta wrote in an appreciation. “The vivid illustrations and clear, concise explanations within those pages sparked a curiosity in me that has fueled my academic journey ever since. … (Stryer) had a unique ability to distil complex concepts into accessible knowledge, igniting a sense of awe and excitement in his students.”

In 1976, Stryer returned to Stanford Medicine to establish the department of structural biology, which he chaired for three years. He was a member of the Journal of Biological Chemistry editorial board in 1976 and 1977.

During a sabbatical in 1989, he helped found Affymax, a biotech company that used light to generate microarrays for drug discovery. He later led the scientific advisory board at Affymetrix, a spinoff company that successfully manufactured DNA chips that facilitate high-speed genetic analysis. He retired from Stanford in 2004 and served as chair of the scientific advisory board of Affymetrix until 2010.

Stryer was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the National Academy of Sciences and the American Philosophical Society. He received the American Chemical Society Award in Biological Chemistry, the American Association for the Advancement of Science Newcomb Cleveland Prize and the European Inventor of the Year Award.

In 2006, President George W. Bush awarded Stryer the National Medal of Science, the nation’s highest recognition for scientists and engineers. According to a Stanford obituary, Stryer told Bush that, as an immigrant to the U.S., he was especially grateful for the honor.

“He was a deeply caring person, devoted to his family and his coworkers,” Jeremy Berg, a professor of computational and systems biology and associate senior vice chancellor for science strategy at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and now co-author of Biochemistry, said. “He pushed himself and those around him fairly hard but always with a sense of the joy of accomplishment rather than less noble pressures.”

Stryer loved to travel and had a passion for nature and wildlife photography. He visited India, Morocco, Rwanda, Tanzania, Madagascar, Chile, the Galapagos Islands, the Arctic Circle, Antarctica and more.

He is survived by his wife, Andrea; his son, Michael; and four grandchildren.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

Women’s History Month: Educating and inspiring generations

Through early classroom experiences, undergraduate education and advanced research training, women leaders are shaping a more inclusive and supportive scientific community.