My study-abroad experience

I’ve wistfully counseled many students as they have prepared for adventure abroad, wishing I could go along. So, when an opportunity came for me to spend two summer weeks immersed in bioanthropology in northern France, I jumped.

The chance came in the form of collaboration with Megan Moore, a professor at Eastern Michigan University. Moore, a forensic bioanthropologist, had begun working with French scientists and physicians to study the bones unearthed during a construction project in Saleux, France, in 1993. The construction site had been a burial ground for Merovingians and contained nearly 2,000 individuals buried between 700 and 1200 AD. The collection of artifacts, now housed near an estate that is open to the public, offers a rare opportunity to learn from the ancient bones and teeth about diet, nutrition and injury. The estate is where we worked.

My experience in chemistry and molecular biology and my willing attitude to do anything was useful to the project. Thus, I traveled by plane and train in late June to Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, a village located near the salt flats of northern France. A charming village originally home to fishermen, it still has the ramparts and walls of the castle dungeon that held Joan of Arc. There, I met the group, which had arrived a few days earlier, and spent the weekend in cultural pursuits to Paris museums and sites.

The 13 participating students shared one large house, while the faculty and family members shared a house around the corner in the shadows of the medieval castle walls. Students from the University of Michigan–Dearborn, Eastern Michigan University and the University of Nebraska all had been well-trained in advance, and each one was assigned a specific research project.

Travelogue

I kept a diary of the adventure on Facebook. In this way, I was able to reflect on the adventure but also reach an audience of scientists and relatives who were happy to have insight into a scientific investigation. Here are some example posts:

- Professor Megan Moore points out a feature in a bone structure. They were making 3-D images of small bones, mandibles (to see hidden teeth), jaws and skulls. Structures in the jaw along with knowledge of diet are useful indicators of the food eaten, jaw strength and mastication, while vertebrae damage indicates other stressors.

- Linda is studying the plaque on the teeth. Yes, these individuals do indeed have dental plaque, which is a thick mass of mineralized biofilm, microflora (bacterial debris) and minerals that harden on your teeth. We humans still deal with plaque!

- If we are lucky and find an individual with minimal dental decay and a tooth that has not been ground down to the dentine, there is a chance that inside the tooth is some DNA. Using this DNA we can perform “DNA fingerprinting” and learn about the history and migration patterns of the individuals or other specific details. For example, this might help us identify the sex in a juvenile skeleton.

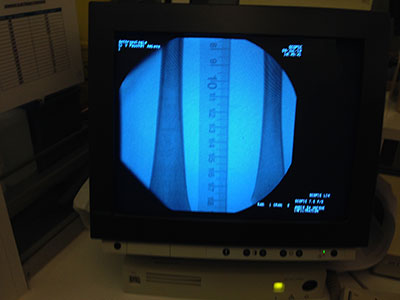

- Several of us traveled to Amiens to take the samples for isotope and DNA analysis and to have a select group of bones X-rayed. Emily identified teeth samples indicating hyperplasia due to stress, and now long bones from these individuals are examined by X-ray for Harris lines that confirm growth stressors. From the position, they can determine the age of stress. Many thanks to Christophe Obry and colleagues at Victor Pauchet private hospital in Amiens!

All the students were familiar with osteology — impressively so, as they often patiently explained the skeletal parts to me. (Disclaimer: Trained as a chemist, I have never become overly familiar with bones, tendons and other working parts of the human form.) In addition to their skills, the students had learned the ethics of working with the bones, showing reverence, respect and a bit of awe for the population.

Moore specializes in nutrition and osteology, and Emily Hammerl, a bioanthropologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, brought her expertise and equipment including a portable X-ray machine and 3-D imager. Thus, everyone was busy for the next two weeks evaluating, cataloguing, measuring, celebrating the Fourth of July, dining as a group and journeying to see the impressive Notre Dame gothic Cathedral in Amiens about an hour southeast of Saint-Valery-sur-Somme.

My primary role was to assist student Linda in her sample preparation for studies on the isotope analysis of the dental plaque and rib bone. Although not widely appreciated by many of us teaching photosynthesis, differences in how heavy isotopes are assimilated by C3, C4 and CAM plants provide important clues about diet. Research has demonstrated that both dental calculus (the hardened plaque) and bone collagen provide relevant data about food sources.

In addition to my personal desire to experience and learn something new, I wanted to find out more about study-abroad experiences. Many biochemistry and molecular biology students are interested in study abroad – as an opportunity to experience a different culture, to learn or to perform humanitarian work. There are commercial and campus opportunities, with those in the category of helping typically aimed at educating children, working in the environment or participating in some medical relief. Rare are opportunities that include biochemistry research with history and culture.

I also went to find out how much work is required to offer such an experience to students. It is not easy to run the program and requires months of preparation, fundraising and organization. Moore never stopped moving, and as the only person fluent in French, she was called upon to be faculty expert, driver, interpreter, organizer, diplomat and fun maker. It was hard work.

Just as important: I found a new research collaboration. The experience was insightful, rewarding and fun. I hope that more study-abroad opportunities can be created for students interested in research and cultural experiences.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Black excellence in biotech: Shaping the future of an industry

This Black History Month, we highlight the impact of DEI initiatives, trailblazing scientists and industry leaders working to create a more inclusive and scientific community. Discover how you can be part of the movement.

Attend ASBMB’s career and education fair

Attending the ASBMB career and education fair is a great way to explore new opportunities, make valuable connections and gain insights into potential career paths.