Peering below the surface

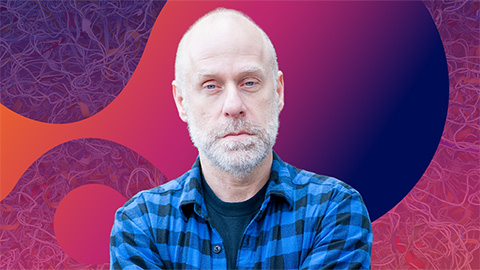

The letter of evaluation offers your first, and sometimes only, view of a job applicant as a whole person. Here are some tips from Pete Kennelly on making the best use an applicant's letters.

The X factor in personnel evaluation

Today more than ever, letters of evaluation constitute the X factor in personnel evaluation. Fifty years ago, the biochemistry and molecular biology community was still that – a community. You could routinely leaf through the three to four hundred pages of your monthly copy of the Journal of Biological Chemistry from cover to cover and rely on seeing your colleagues every year at the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology’s annual meeting in Atlantic City. At a time when everyone knew or knew of everyone in the profession, new faculty members and postdocs often were hired on the basis of personal contacts rather than bulky committees navigating page upon page of official procedures and policies.

Today, by contrast, there are many institutions, both academic and industrial, where biochemistry and molecular biology PIs, staff and trainees who work in the same building would be unable to recognize many of their neighbors by name or even appearance. Consequently, the letter of evaluation frequently offers the first, and potentially only, opportunity to humanize the evaluation process, to delve into the realms of motivation, character, creativity, perseverance, responsibility, independence, initiative, leadership, respect for others, and integrity. In a world where potential mentors and employers place increasing emphasis on complementary skills such as teamwork and ethics, letters of evaluation offer insights beyond the metrics of the vitae and into personality and character.

The humanizing effect of these letters also can benefit the applicant. The flexibility of the letter format enables the author to bring up qualities and experiences not apparent from one-dimensional metrics such as grades, test scores, papers published, impact factors, and so on. Letters of evaluation offer the author an opportunity to bring to life the candidate who does not test well but has great hands and good instincts, whose personality and behavior help create a positive atmosphere in the laboratory, who relishes a challenge, or who has a knack for explaining difficult concepts in terms students can understand.

Since the people who author these letters of evaluation also serve on search and admission committees, you would expect them to exhibit a good feel for what the reader is looking for as they write. Yet despite the potential benefits to both the candidate and the potential employer or mentor, all too often letters of evaluation can be surprisingly generic in form and uninformative in content. There is information to be gleaned, however, even from a poorly written letter, particularly when multiple letters are available to compare and contrast.

One letter, three agendas

Today’s litigious atmosphere has contributed significantly to the monotonous homogeneity so frequently encountered in contemporary letters of evaluation. Other factors include the increasing sterility of teacher-student interactions that has accompanied the steady growth in class size and the intrusiveness of social media on campus. But in the final analysis, the letter of recommendation has been plagued by an inherent ambiguity since its inception: Whose letter is it? Whose interests take priority?

Certainly the members of the search, admissions or awards committees who request the letters, and to whom the letters are in fact addressed, would appear to have a strong claim as the party whose interests should be paramount. The recipient expects to receive a letter that offers a comprehensive, balanced description of the applicant’s professional accomplishments and ability capped off by an objective overall ranking consistent with the text. The reader would expect to find comments regarding the applicant’s professional potential, command of relevant knowledge and techniques, independence and initiative, communications skills, ability to work with others, and so forth. No one is perfect: In addition to highlighting the applicant’s strongest attributes and most significant accomplishments, a reader-directed letter will contain a few thoughtful and constructive comments on areas where the applicant may lack experience and training or need further work.

Many evaluators, on the other hand, cast themselves in the role of advocate. Rather than providing an independent evaluation, the author sees himself or herself as an agent charged with aiding the applicant in reaching his or her goals in much the same way a realtor works with a homeowner to sell his or her property. Any response to a request for numerical ratings or a relative ranking – a common feature of graduate school and fellowship applications – will be skewed heavily toward the very highest values. The signature of the advocate-author is a stridently positive tone juxtaposed against a striking unevenness in coverage. While most authors generally will say very little when they struggle to find positive things to say, the advocate-author adopts a more extreme all-or-nothing interpretation. Hence the letter will seem incomplete as some aspects of the candidate’s abilities and accomplishments will be described in great detail, whereas comments on some related topics will be nowhere to be found.

In some cases, the evaluator may have let some personal agenda intrude into his or her evaluations. Since one relatively painless way to divest oneself of a weak performer is to have him or her secure another position elsewhere, an evaluator may be tempted to paint an overly rosy portrait. Conversely, the desire to hang on to a well-trained and productive member of their research group may tempt some principal investigators to hold back in their evaluations. In both cases, the key indicator will be a disparity between the descriptors used and the documented productivity of the candidate. For example, if a trainee is described as the leader and intellectual driving force behind a particular project yet consistently is buried in the “et al.” portion of the author list on the relevant papers, suspect over-selling!

Some authors are animated by a vivid fear of legal retribution should a candidate’s search prove unsuccessful. Their letters contain repeated stipulations that the other evaluators are more qualified to comment upon the applicant’s skills and abilities. Letters in this genre tend to be relatively brief and dominated by vague, innocuous descriptors that neither inform nor inflame.

Multiple letters are key

Always request multiple letters. Pattern recognition is one of the more reliable ways to tease out information about a candidate whose individual letters of evaluation are frustratingly vanilla. If multiple evaluators fail to devote any space to some obvious topic, odds are that they share significant reservations in this area. Similarly, if multiple evaluators state that an applicant’s grades are not reflective of his or her performance and abilities, it is a good bet that this is indeed the case.

The identities of the evaluators selected by the candidate also can be revealing. One can feel positive and reassured when each evaluator unhesitatingly describes his or her relationship to the applicant in specific terms. Other positive signs are that the trainee initiated contact or met regularly with the investigator in question. Weak trainees frequently avoid contact with faculty or group leaders, preferring to work through an intermediary such as a fellow student or staff member. A person who asks other trainees to write letters instead of experienced and trained leaders may be technically quite competent but personally insecure and immature. Omission of the applicant’s last mentor or supervisor from the list of evaluators suggests that you proceed with caution.

In describing the candidate’s strengths, do the evaluators illustrate their points with specific examples? Supporting anecdotes should flow easily from someone who has substantive, personal knowledge of the candidate. The order in which specific strengths are presented also can be a telling indicator. The mention of some fundamental characteristic – for example, “an extremely talented experimentalist” or “an original and innovative thinker” – suggests a very high overall opinion of the candidate, whereas “a great command of the literature” suggests a person struggling to find something positive to say about someone whose abilities and goals may be mismatched. On the other hand, in my experience, very few authors include statements like “I would gladly hire the candidate back in future” or “the candidate would be welcome anytime as a member of my research team” unless prompted, so when this phrase is freely volunteered, it should be noted carefully.

Learn to recognize avoidance

When an evaluator is convinced, based on his or her own direct interactions with a trainee, that the candidate is strong or even exceptional, in most instances the enthusiasm is palpable. As you read the letter, you get the clear sense that the evaluator is having trouble keeping it to a reasonable length – that he or she simply can’t say enough. While letters for good or solid candidates may lack the same energy, they tend to be unhesitatingly direct in tone. On the other hand, any behavior suggestive of avoidance, such as difficulty in selecting a first strength, generally is indicative of an author struggling to find some way to make the evaluation sound better.

A classic model of avoidance is the letter that spends three paragraphs describing in great detail the trainee’s project, its progress and outcomes. The first paragraph talks about the student’s rotation project. The second relates in painstaking detail progress at the bench and in class during years one and two. The next paragraph relates the experiments that constitute the heart of the thesis. Finally, after negotiating a full page or so of narrative, the reader suddenly finds himself or herself faced with a concluding paragraph that covers the candidate’s specific qualities in three sentences or so. The end. Whenever I see such a letter, I get the impression that the author set a goal to write something long enough to suggest a positive opinion. Once that critical length was reached, usually a full page, the author could now safely move to the denouement, which he or she dispatched in a few short sentences. This structure is ideally suited to the agenda of the author focused first and foremost on providing no opening for a litigator.

Where do we go from here?

Reviewing a candidate’s credentials should be done in a holistic fashion. Your goal is to reconstruct stories of the candidates’ educational and professional development to date and obtain a feel for their future trajectories. Learning to read between the lines of letters of recommendation should be viewed as a game of “gotcha.” Identifying outliers and unearthing underlying trends can help bring a candidate’s abilities and qualifications into focus, leading to better matches of trainee with mentor and applicant with position.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Life in four dimensions: When biology outpaces the brain

Nobel laureate Eric Betzig will discuss his research on information transfer in biology from proteins to organisms at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

Redefining excellence to drive equity and innovation

Donita Brady will receive the ASBMB Ruth Kirschstein Award for Maximizing Access in Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Upcoming opportunities

Calling all biochemistry and molecular biology educators! Share your teaching experiences and insights in ASBMB Today’s essay series. Submit your essay or pitch by Jan. 15, 2026.

Mapping proteins, one side chain at a time

Roland Dunbrack Jr. will receive the ASBMB DeLano Award for Computational Biosciences at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Exploring the link between lipids and longevity

Meng Wang will present her work on metabolism and aging at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7-10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Upcoming opportunities

Calling all biochemistry and molecular biology educators! Share your teaching experiences and insights in ASBMB Today’s essay series. Submit your essay or pitch by Jan. 15, 2026.