‘I can do it without making a face’

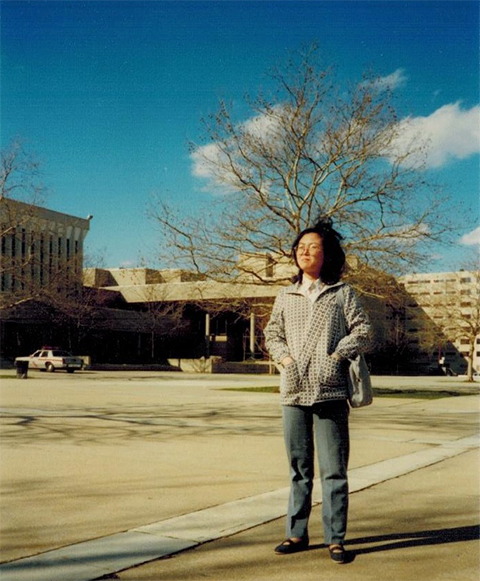

Thirty-five years ago, I’d just graduated from college in China and was admitted to a few graduate programs at universities in the United States. This was a dream come true, and I was excited.

It was a turbulent time in Beijing that summer, with the student protests and a brutal government crackdown in Tiananmen Square. The process of obtaining a passport and visa was both tedious and nerve-racking. In the long lines at the U.S. embassy waiting for visa interviews, everyone feared the Chinese security bureau would strip away their passport and visa for being involved in the student movement.

On August 16, 1989, I bid farewell to my proud yet worried parents and boarded Air China’s Boeing 737 aircraft to fly across the Pacific Ocean. It was my first flight, and I was tense. I was eager to experience a fresh new life but also ambivalent about leaving my family and friends and everything familiar and comfortable behind.

I had passed my English as foreign language exam with near-perfect scores, but I was anxious about practicing English in the real world in a new land. On top of that, I would have to get used to being on my own for every decision, big or small. Throughout college, I counted on counsel and support from my parents. I took it for granted and even at times, being an independent young soul, despised it.

I knew letters across the ocean would take weeks to deliver. International phone calls, like international flights in those days were expensive, and I would only be able to afford them rarely.

After more than 20 restless hours flying across half the globe, through an entry stop in San Francisco, I landed at JFK airport in New York City, carrying two large suitcases packed full of everything my parents deemed necessity and could cram inside. It was a couple of weeks before my classes were to commence.

I was enrolled in the biochemistry graduate program at the City University of New York as a Ph.D. student. I was to be a teaching assistant at Hunter College, part of the CUNY graduate program. My financial aid included a tuition waiver and a stipend of almost $9,000 covering 9 months; it doesn’t sound like much money, especially to live in New York City, but it was enough for a grad student to live a frugal life. I never had to wait tables or deliver food to pay for my next meal, like some other students I met; instead, I could focus on my academic work without distraction.

I lived in a furnished dormitory that Hunter offered to its resident graduate students for $450 a month on the nursing school campus. It was between the New York University Medical Center and an affluent East Village neighborhood where I heard movie stars like Katharine Hepburn lived back then.

In China, I’d shared a single room and bunk beds with seven other girls in a college dorm, so I felt on top of the world with a spacious and sunny room all to myself in a safe, secure and well-maintained building. Campus shuttles running back and forth to the Park Avenue main campus also provided enormous convenience.

I wrote to my parents every couple of weeks, reporting my adventures and telling them not to worry about me. I longed to hear from them. My first letter from home arrived a few weeks after the fall semester began. I returned to the dorm from school late on a weekday afternoon, got off the shuttle and walked past the front desk to check the mailbox in the hallway. There was a letter lying there, waiting for me. I recognized my mother’s handwriting. As soon as I locked the mailbox, I tore open the envelope on my way to my room.

My memory of that first letter from my parents is hazy, but I recall clearly that it started with “My dearest daughter.” I burst into tears reading those words, weeping while I walked down the corridor. I didn’t realize until that moment how much I missed them. It was barely a month since I hugged them goodbye, but it felt like a century.

As a first-year graduate student, I had lab rotations in the biology department at Hunter. As a teaching assistant, I set up labs for college students and ran the lab sessions weekly, with another senior TA. To take classes, I traveled by subway to the CUNY Graduate Center near Time Square. There I met with fewer than a dozen other first-year grad students in biochemistry, some from other CUNY campuses. A few were from China. We all shared lectures and became friends. We visited CUNY’s library together searching for textbooks after a Friday lecture; we went to see the United Nations on the East Side after a mid-term exam. Most days, however, we rushed back to our respective home colleges for labs, TA duties and even part-time jobs.

The adjunct instructor I worked for at Hunter was a serious middle-aged woman who often wore oversized, bright earrings in lab sessions. She was strict with both TAs and college students, but rumor had it she brought candy corn for Halloween.

In one session, she pulled out a barrel of earthworms that the students needed to dissect the next day, picked one out quickly and smoothly demonstrated the procedure. When it was time for us TAs to pick up the earthworms, I felt uneasy in my stomach and made a face while I picked up a worm.

“Don’t let people see that face,” I heard her shouting across the room.

I knew that shout was directed toward me.

I transferred to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia the following year. I continued my graduate studies and earned a Ph.D. in molecular biology from Penn several years later.

I’ve grown personally and professionally over the years, overcoming much bigger obstacles in life. I still don’t like picking up worms or insects, but I know I can do it without making a face now — as I was trained to 35 years ago.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges —microaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Black excellence in biotech: Shaping the future of an industry

This Black History Month, we highlight the impact of DEI initiatives, trailblazing scientists and industry leaders working to create a more inclusive and scientific community. Discover how you can be part of the movement.

Attend ASBMB’s career and education fair

Attending the ASBMB career and education fair is a great way to explore new opportunities, make valuable connections and gain insights into potential career paths.