American stranger: Thoughts on identity and inclusion

I am a first-generation, American-born woman of Asian descent, and as such, I have never experienced being part of the majority in the room. I have worked in academic science since the age of 19. In every laboratory, there has been only one of me — the American-born Asian — even when there are Asians born in Asia but training in the United States. I am different from the Asian-born, and I am different from non-Asian Americans.

As a result of policies designed to keep Asian immigrants out of the U.S., such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Immigration Act of 1924, sometimes I feel like a stranger in my home country. Thanks to the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, designed to allow immigration of Asian doctors and engineers preferentially, Asian Americans are overrepresented within these professions. Therefore, Asians are not considered a minority in fields related to science, technology, engineering and mathematics, including academic science. But we Asians — American born or not — still are viewed as different from other Americans.

I am an associate professor and the director of trainee recruitment, development and diversity in pharmacology and toxicology at the Indiana University School of Medicine. I am fortunate to be part of a system that values diversity, equity and inclusion.

In my roles as an educator and mentor, I spend a lot of time considering the question of best practices for DEI in academic sciences because I want to improve the graduate education experience. My goal is to make it less awkward for my students than it was for me.

I have encountered countless clichéd microaggressions. People ask me where I am from or speak to me in one of a variety of Asian languages. They may be trying to be friendly, but I have no idea what to say in response. People have asked me, “What’s the strangest thing you’ve ever eaten?” Sometimes Asian-born peers muttered under their breath in their native language, assuming I had no idea what they were saying, “That’s the American. She’s got it so easy,” because I could apply for federal grants during my Ph.D. and postdoc years but my peers who were not U.S. citizens could not.

Another island

I want my graduate students to have a better cultural experience during their Ph.D. training. Right now, my research group happens to be entirely composed of women. I am proud of each member for their strong, independent character. One student in particular comes to mind. She is from Puerto Rico, and her native language is Spanish.

Following the Spanish–American War, Puerto Rico became a territory of the United States. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens and are subject to U.S. laws, but they lack voting representation in Congress and cannot vote in U.S. presidential elections. I am surprised at how many people don’t know these facts.

Like me, my student exists on her own island, and her situation provides a mixed message —you are kind of one of us, yet different. As a U.S. citizen, my student is eligible for federal grants, unlike Latinx students who are not from U.S. territories. However, Spanish is her native language, and unknowing individuals assume she is foreign.

I see how others interact with my student and how they react to her pronunciation of English words. I see when she has to stop and think an extra minute to convert a Spanish word to English in her head. She struggled with written English when she started out in graduate school but has worked very hard with me to overcome these difficulties.

Taking action

The other members of the lab, all native English speakers, pitch in and help review her written documents. I explained to them the biases others may have when they see mistakes in this student’s written English. I told my other students that I did not want people to disregard her intelligence when they see small issues like spelling errors, because in my opinion, she is a highly capable scientist. I wondered, What is the best thing to do to help her succeed?

We worked out a plan to use both Spanish and English in the lab. Members of the lab now label reagents, write orders and leave notes in Spanish and English. We practice saying scientific terminology in Spanish and try to have basic conversations. My student uses Spanish and explains to me the nuances of her language (each Spanish-speaking country or community is slightly different); we discuss how its grammar is different from English grammar.

In addition to these changes in the lab, my student was able to include a faculty member on her dissertation committee who is also from Puerto Rico.

My student has come a long way, and I have learned a little bit of Spanish. I believe this scenario benefits both of us, even if my pronunciation of Spanish phrases does not sound quite right or I accidentally write on the message board that the lab meeting will be in my bedroom instead of the conference room.

This article began as an idea to discuss best practices for DEI in biomedical sciences. As I began writing, I realized the word “best” projects finality, and in the realm of DEI, there is no standard set of practices that works for everyone.

I believe a unifying factor underlies many of the anxieties we all feel toward things that are different: the desire to be included and belong. As my teaching methods evolve, I plan to work on cultivating inclusive practices because everyone deserves to be provided with a path to their individually defined success.

Relevant reading

“The US biological sciences faculty gap in Asian representation” by James Meixiong and Sherita Hill Golden, the Journal of Clinical Investigation, July 1, 2021.

“Asian Americans: The overrepresented minority?: Dispelling the ‘model minority’ myth” by Corinna J. Yu, ASA Monitor, July 2020.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

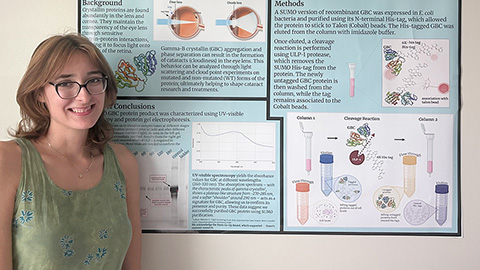

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.