James Bryant Howard (1942 – 2022)

James Bryant Howard, professor emeritus of biochemistry at the University of Minnesota School of Medicine, died unexpectedly on Feb. 13 in Cochiti Lake, New Mexico. He was 79.

Howard had had been a member of the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology for more than 40 years, and he served on the Journal of Biological Chemistry editorial board from 1986 to 1991.

Born April 25, 1942, in Indianapolis, Howard completed his Bachelor of Arts in chemistry from DePauw University in 1964 before heading west to graduate school at the University of California, Los Angeles. He received his Ph.D. in biological chemistry at UCLA in 1968 as one of Alex Glazer's first graduate students. Howard often said that the exciting environment for biochemistry at UCLA catalyzed his life-long passion for protein chemistry, structure and function.

After a postdoctoral position with Fred Carpenter at UC Berkeley, Howard joined the biochemistry faculty at the University of Minnesota School of Medicine in 1971, where he remained until becoming emeritus in 2002. Among his notable research accomplishments were his identification of the modified histidine in EF-2 that is the target of ADP-ribosylation by diphtheria toxin (with James Bodley), discovery of the alkylamine-sensitive thioester linkage in the active site of the a2-macroglobulin, and a broad series of studies on the nitrogenase proteins, including determining the Azotobacter vinelandii nitrogenase iron protein sequence, identification of the [4Fe:4S] cluster ligands, and characterizing cluster chelation and interconversion reactions.

A great believer in the importance of sabbaticals, Howard arranged to visit the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Harvard, UC Davis and the National Institutes of Health through this mechanism. I first met him while he was on sabbatical with William Lipscomb at Harvard in 1980-81 to crystallize the nitrogenase iron protein. He convinced me of the significance of a structural approach to the study of nitrogenase that, beginning with my postdoc, started a 40-plus year collaboration.

Over the past two decades — until COVID-19 — this collaboration included annual visits by Jim Howard and his wife, Claralyn, to Pasadena, where I work at the California Institute of Technology. Beyond nitrogenase, Howard had a strong interest in geobiology and interacted extensively with the Caltech community in this area. After he became emeritus, the Howards moved to New Mexico, and his research interests included isolation and characterization of nitrogen-fixing autotrophs in his home lab from the year-round seeps in the surrounding mesas.

Howard was a true natural philosopher; he loved designing experiments, going over results, attending seminars and discussing what it meant to prove a result. His curiosity was infectious. He focused on the details of experimental design and enjoyed discussing with students and postdocs how to accurately quantitate protein concentration, the temperature dependence of pH, and the importance of ionic strength effects — topics that are typically considered trivial but disastrous consequences can result if they are overlooked. A natural skeptic, Howard had a high bar for being convinced, and there was no bigger satisfaction than getting with him to that point. Beyond science, he read extensively and loved jazz and art, cycling and sailing, the outdoors. He was a keen student of academia and the bigger issues of life and society.

Our thoughts go to Claralyn Howard; their daughter, Cathy, and her husband, Tony Grundhauser; granddaughters Emma and Lucy; and Jim’s sister Aleta Howard at this difficult time.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Women’s health cannot leave rare diseases behind

A physician living with lymphangioleiomyomatosis and a basic scientist explain why patient-driven, trial-ready research is essential to turning momentum into meaningful progress.

Making my spicy brain work for me

Researcher Reid Blanchett reflects on her journey navigating mental health struggles through graduate school. She found a new path in bioinformatics, proving that science can be flexible, forgiving and full of second chances.

The tortoise wins: How slowing down saved my Ph.D.

Graduate student Amy Bounds reflects on how slowing down in the lab not only improved her relationship with work but also made her a more productive scientist.

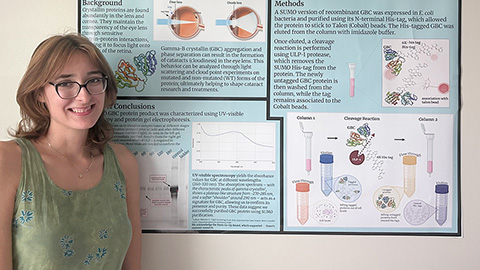

How pediatric cataracts shaped my scientific journey

Undergraduate student Grace Jones shares how she transformed her childhood cataract diagnosis into a scientific purpose. She explores how biochemistry can bring a clearer vision to others, and how personal history can shape discovery.

Debugging my code and teaching with ChatGPT

AI tools like ChatGPT have changed the way an assistant professor teaches and does research. But, he asserts that real growth still comes from struggle, and educators must help students use AI wisely — as scaffolds, not shortcuts.

AI in the lab: The power of smarter questions

An assistant professor discusses AI's evolution from a buzzword to a trusted research partner. It helps streamline reviews, troubleshoot code, save time and spark ideas, but its success relies on combining AI with expertise and critical thinking.