The job of a scientific director

Gabrielle Rushing is the science program director at CSNK2A1 Foundation, an organization dedicated to finding a cure for Okur–Chung Neurodevelopmental Syndrome and supporting patients and families affected by the rare disease.

A new employee at a new foundation

The organization is new, launched in 2018, because the disease is newly recognized, having been characterized and named in 2016.

Rushing was hired as the organization’s first full-time employee in April of this year after Jennifer Sills, the president and founder of the foundation, attended a bootcamp for parents working to find cures for their children with rare diseases. Sills’ daughter has OCNDS. It became clear that she needed a scientific director to move the foundation’s scientific efforts forward.

The job was originally advertised as a part-time position, but soon Rushing was asked to work full time. She said she could’ve made part time work (“I have my bartending license!” she noted), but she was happy for the chance to devote all her time to the mission.

Rushing’s job as scientific program director resembles that of a principal investigator in academia. “I’m developing the research roadmap,” she said.

As a new employee of a new foundation studying a new disease, she must approach things methodically and make good decisions.

She is currently working on her landscape analysis. That entails “assessing where we’ve been, where we are and where we want to go.” Specifically, she’s reading up on what’s known in the field, figuring out what projects are ongoing, and identifying areas where there is a need for more research. For example, she found that no one was studying induced pluripotent stem cells from patients, an aspect of research she wants to pursue.

The biggest difference between her role and a PI’s role is that she doesn’t have a lab. All the research that she plans and organizes is done by collaborators or through outsourcing. The foundation hires contract researchers, collaborates with academics and partners with industry.

Much of her time is spent on writing grants to fund these research endeavors. These proposals often are similar to the R01 grants that PIs at universities write. She recently applied for a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute grant that funds programs that keep patient needs at the forefront.

She said she sees grants as an opportunity to catalyze potentially fruitful collaborations between different researchers in academia. She recently collaborated with a researcher in France to submit an application to the Department of Defense’s Autism Research Program.

The research plan she’s developing is informed by her literature knowledge but also by meetings with lab and clinical scientists, meetings with the organization’s scientific advisory board (which includes physicians Volkan Okur and Wendy Chung, after whom the syndrome is named), and attending conferences.

Another important way she informs her research plan is through learning from patients and families. She listens to what they need, what problems they are encountering in daily life, and what their priorities are. She said she is committed to developing a research plan that includes the patients and families.

“I’m presenting a roadmap not just having patients be the research (subjects) but having them be engaged,” she said. She brought up a phrase that was first was used in the disability rights movement in the 1990s: “Nothing about us without us.”

Rushing said she wants to include patients and families but “it’s just hard because caregivers are busy.”

Getting into patient advocacy work

Rushing started on her path to patient organizations while earning her Ph.D. at Vanderbilt University. She did an internship at the TSC Alliance, a patient advocacy organization for the genetic disease tuberous sclerosis complex.

Rushing said she loved the work. She helped organize the organization’s patient-focused drug-development conference, at which patients share their experiences, report on the side effects of drugs that need to be addressed, describe symptoms that need more attention, and talk about things that limit daily life that researchers might not realize. The goal was to make sure the researchers are working on projects that will meet the needs of patients.

After her internship, she became a research consultant for the Thisbe and Noah Scott Foundation, which advocates for childhood neurological diseases. She then returned to the TSC Alliance as a full-time associate director of research when she graduated, starting in January 2020.

Today, she's happy in her new role at the CSNK2A1 Foundation. “I thought I would be more stressed than I am, being the only full-time employee, but any stress that I’ve had is mostly self-induced,” she said.

She works hard and really appreciates the support of the people working alongside her to make the foundation work. Rushing said that Sills, the president and founder, is a supportive boss and happy to find ways to help Rushing develop in her career. “She’s always sending me webinars or conference ideas or workshops, like how to use AI tools. She’s very supportive in trying to stay with the times.”

Advice to others

Rushing said that “internships are great” for people thinking of moving into patient advocacy. “They give you a sense of the day-to-day and give you networking opportunities,” she said.

She also suggested improving your project-management skills — and even taking business principles classes. Public speaking skills can be extremely helpful as well, she said.

It’s also important to consider what the environment will be like. At her organization, and at other small organizations, there isn’t necessarily much interpersonal interaction if you are working remotely, as Rushing does. “If you are extroverted and like day-to-day team interactions, it might not be the thing for you. You have to be self-driven and not need a lot of immediate feedback,” she said.

Rushing said that she has always been independent, and this job fits her personality well: “I like the flexibility and freedom this job allows me to have in my life.”

About the syndrome

Okur–Chung Neurodevelopmental Syndrome was characterized in 2016 by sequencing all the expressed regions of DNA, or the exome, of more than 4,000 children who had developmental delay or intellectual disability.

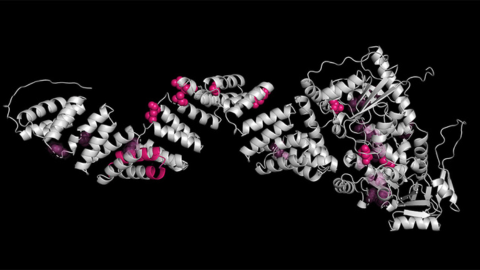

In that sequencing data, five children were found to have mutations in the CSNK2A1 gene, which codes for a subunit of a protein kinase, CK2.

Since then, more patients have been diagnosed with OCNDS, but it is still extremely rare; as of a review published in 2022, there were 51 known cases around the world, though it's almost certain there are more people who have broad diagnoses (such as "developmental delay") that if sequenced would turn out to have OCNDS.

People with OCNDS have a range of signs and symptoms that can vary from person to person, but the most common ones include developmental delay, including language and motor delay, intellectual disability, decreased muscle tone and behavior difficulties, including symptoms that overlap with autism and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Some patients also have seizures, difficulty eating and gaining weight, a tendency toward ear and lung infections, and sleep/circadian rhythm issues.

There are no Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for 95% of rare diseases, and in many cases there is not much support from the pharmaceutical world to invest in and find treatments for small markets. This forces patients and their families to push for research and search for treatments themselves by starting organizations like the CSNK2A1 Foundation.

Recruiting sources of expertise, such as a scientific director familiar with biomedical research, is essential to move the field forward and work toward finding suitable medications or even a cure.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Friendly reminder: May 12 is the early registration and oral abstract deadline for ASBMB's meeting on O-GlcNAcylation in health and disease.

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.

Quieting the static: Building inclusive STEM classrooms

Christin Monroe, an assistant professor of chemistry at Landmark College, offers practical tips to help educators make their classrooms more accessible to neurodivergent scientists.

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.