How military forensic scientists use DNA to solve mysteries

Military DNA identification happens at the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System, or AFMES, at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. AFMES aims to “(i)nvestigate deaths, identify the fallen (and) improve readiness.”

In addition to DNA identification, staff at AFMES perform forensic pathology, during which they identify the cause and manner of active service member death and investigate crime scenes and aircraft accidents; they also perform forensic toxicology, which encompasses all aircraft, ship and ground accidents as well as DUI investigations and autopsies.

I spoke with two forensic DNA analysts at AFMES in the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory, or AFDIL, Luisa Forger of the Past Accounting Section and Malachi Weaver of Current Day Operations.

The Past Accounting Section identifies the remains of prisoners of war or those missing in action from as far back as World War II and reports their finding to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency. Conversely, the Current Day Operations department identifies the remains of current service members.

Daily work in the Past Accounting Section

“There isn’t a typical day,” Forger said. “There’s a lot of flexibility.” On any given day Forger said she might be prepping bone or tooth samples for DNA extraction, extracting genomic material, preparing DNA libraries for next generation sequencing or writing up a report about the findings.

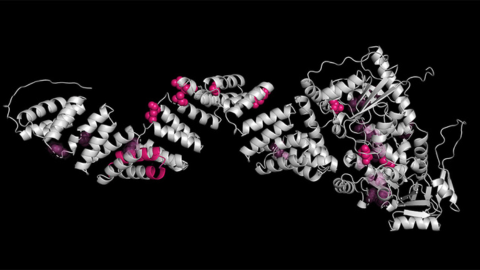

Forger uses mitochondrial DNA, or mtDNA, to identify individuals for a few reasons. Unlike genomic DNA, mtDNA is protected inside the mitochondria, and it is circular which prevents the degradation from the ends, which can damage linear nuclear DNA. These qualities give mtDNA a higher chance of being intact enough for sequencing. After up to 80 years in nonideal storage conditions, as might be the case for WWII remains, finding nondegraded DNA is crucial.

In addition, using mtDNA also allows Forger to identify the person through any family member within the maternal line, since mtDNA is inherited from mother to child without genetic recombination.

Remains can be identified by comparing the DNA in the sample to a database of family members’ DNA. Sometimes outside information can guide a search, but many searches are blind and compare the sample’s DNA with the entire database. Though family members of missing service members are not required to provide DNA samples, most do voluntarily since they want their missing relatives found and identified.

“One of the best parts about this (job) for me is that there’s a really tangible positive effect when we are able to finally identify the remains,” Forger said. “I’ve gotten to meet a couple families.”

While Forger said her job is rewarding; it can also be challenging. Samples from 50 or 80 years ago likely were stored in poor conditions, she said.

“The trickiest part is — at least for me — the kind of samples we’re working with. They are low quality samples,” Forger said. “Troubleshooting and trial and error to just get a DNA profile can be a lot of work.”

Daily work in Current Day Operations

Weaver in Current Day Operations agreed that there’s no typical day for him either, “I like the variety of cases,” Weaver said. “You never know what you’re going to get.”

In addition to identifying military members, the Current Day Operations team sometimes works on nonmilitary identifications. The team recently identified the remains from the Titan submersible disaster, and sometimes works on medical or criminal cases.

Unlike Past Accounting, Current Day likely know who the remains belong to and only need to confirm it, “an extra check,” as Weaver described it. The team relies on a blood sample repository. In the years since DNA became a reliable way to identify people, service members have been required to provide a small blood sample that is stored on a card and can be accessed should a DNA confirmation be needed. There are currently over 9 million cards with individual blood samples in the repository.

Weaver often splits his time between working in the lab or at a computer doing analysis or administrative tasks. While analyzing DNA, he typically receives tissue samples from the evidence custodian, who retrieves them from the morgue, as well as the associated blood stain card from the repository. Weaver then carefully and separately — to avoid contamination — extracts the DNA from both for comparison.

Though Weaver knows his efforts make a difference, “it can be a little isolating because we don’t have a direct tie to the outside world,” he said. But the people he works with make it worthwhile.

“I love my team,” he said. “We work really well together.

Paths to the jobs

Growing up, Weaver had strong interests in both science and criminology. He attended Duquesne University in Pittsburgh and pursued a combined 5-year bachelor’s and master’s program in forensic science, during which he took a course in DNA methods.“I got really into every step of the process; I loved how (DNA) became the gold standard of identification,” he said. Weaver applied to AFDIL immediately after graduation and has been there for the last seven years.

“I really clicked with the people here,” he said.

Weaver originally joined the Past Accounting department and said people often start there since the department is bigger with dozens of staff. Six months later, he switched to the smaller Current Day department, which only employs 13 people.

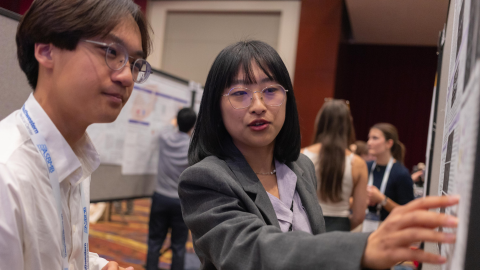

Forger initially applied to college as a photography major but, before starting, realized she wanted to study something more practical and decided to major in biology. Unsure of exactly what she wanted to do, she took stock of what she enjoyed and was interested in. Shows like Bones that demonstrate forensic biology intrigued her, so she earned a master's in forensic science from Virginia Commonwealth University, focusing on DNA forensics.

During a research fellowship through ORISE at the FBI, a friend mentioned that Forger should apply to the AFDIL, and she has now been there for the last five years.

Forger encouraged people interested in the field to take opportunities that they see: Doing research and meeting others in the field. She said the forensic science community is small.

“You’re going to see a lot of the same people every year at meetings,” Forger said. “Go to meetings and network.”

Qualifications and standards

In both Past Accounting and Current Day, quality assurance is critical. Forger and Weaver follow rigorous standards established by the FBI to ensure that results are reliable. These standards demand that staff are appropriately trained, facilities are up-to-date and methods are state of the art to get the best results and minimize contamination. Each lab has the freedom to choose what methods, reagents and controls they use, as long as they have first shown the method to be reliable.In addition, there are checks to catch errors: All data analysis must be repeated and confirmed by a second scientist, and everything goes through technical review.

Weaver and Forger said most analysts, like them, have master’s degrees in forensic science. Without a master’s, an applicant needs to show that they have taken relevant courses in biochemistry, genetics and molecular biology from a program that meets the FBI’s quality assurance standards. Weaver and Forger also advised that it is helpful to have some knowledge of statistics and population genetics.

Outside of being an analyst, there are positions at AFDIL that require less training, such as technician roles, and positions that require Ph.Ds., such as research-oriented jobs.

Both Forger and Weaver underscored their love of science and expressed awe at how DNA can survive over the years even buried underground, or in otherwise seemingly hopeless conditions, to provide high quality DNA profiles.

“Sometimes I think, ‘There’s no way this is going to work,’ and then I’ll get a beautiful (DNA) profile,” Forger said. “Or sometimes we test something, and it doesn’t work, but a couple years later we have some new processes, and we can get usable data. The technology catches up.”

Gaining information from remains samples is a concrete way that molecular biology and genetics help solve mysteries and provide closure for military families who have lost loved ones in action.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles

Upcoming opportunities

Coming soon: ASBMB Breakthroughs webinar on biosynthesis and regulation of plant phenolic compounds and a Lipid Research Division seminar on membrane lipids.

Upcoming opportunities

Just added: New fellowship and research award opportunities. Friendly reminder: Submit your abstract for ASBMB's upcoming meetings.

Upcoming opportunities

Friendly reminder: May 12 is the early registration and oral abstract deadline for ASBMB's meeting on O-GlcNAcylation in health and disease.

Sketching, scribbling and scicomm

Graduate student Ari Paiz describes how her love of science and art blend to make her an effective science communicator.

Embrace your neurodivergence and flourish in college

This guide offers practical advice on setting yourself up for success — learn how to leverage campus resources, work with professors and embrace your strengths.

Upcoming opportunities

Apply for the ASBMB Interactive Mentoring Activities for Grantsmanship Enhancement grant writing workshop by April 15.