The quiet creep of Alzheimer’s disease

One day in 2001, Jodi Bottoni came home to find her clothes, shoes, money and small purple beaded lamp on the driveway. Her mother had thrown them out the front door of their home in Venice, Fla. Bottoni, who in her 40s had moved back in with her mother to care for her, was baffled. She assumed her mother, Jacquie Berg, was becoming an alcoholic and blamed scotch for the irrational behavior. But over the course of the next four years, Bottoni realized her mother’s increasingly erratic behavior, such as hoarding toilet paper in every nook and cranny of the house, couldn’t be attributed solely to alcohol. Something else was wrong. In 2005, Berg was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

Today, Bottoni is one of 15 million Americans who are caring for an Alzheimer’s patient at home. As Gregory Petsko of Brandeis University and Weill Cornell Medical College stated in his 2012 TEDMed lecture, caregivers are “the hidden victims” of the disease.

“I’ve put on tons of weight. I get no sleep. I’m stressed out,” says 54-year-old Bottoni, a bartender-waitress recovering from carpal tunnel surgery. “I have no life anymore. I don’t get to go anywhere. I don’t get to do anything. It’s terrible.”

Bottoni’s now 84-year-old mother, a former acrobat and Arthur Murray dance teacher whose features remind her daughter of the late actress Elizabeth Taylor, talks to her reflection in mirrors, incessantly hums and whistles, hides food in potted plants, and scribbles in coloring books with crayons. Her daughter has child-locked all doors leading out of the house and put a tracking bracelet on her mother’s ankle. During the night, Berg gets up four or five times to go to the bathroom. Bottoni’s 14-year-old Labrador, Morgan, sleeps in her mother’s room, and whenever the elderly woman rises out of bed, “he gets up and shakes his collar,” says Bottoni. “He lets me know she’s up and moving.” If Bottoni doesn’t catch her mother in time, she has to clean urine and feces from the floor, because her mother can no longer coordinate her movements and bodily functions.

So far, Bottoni has refused to put her mother, who adopted her as a child, in a nursing home. “I don’t trust anyone else to take care of her,” she says. “I love her to death. But I don’t know if I can do this anymore.”

The number of people in Bottoni’s shoes will rise if the disease goes unchecked. The global population is aging, and people in their mid-60s begin to become more susceptible to Alzheimer’s disease. By 2050, 100 million people around the world are projected to be stricken with the disease and 300 million people will become their caregivers.

Despite the potentially large number of victims of this fatal disease, Petsko has said, “I hear no clamor. I see no sense of urgency. If you knew an asteroid was going to hit the earth and would kill 100 million people, you would probably expect a worldwide clamor that something be done about it.”

The lack of public clamor, Petsko has argued, is at odds with the buzz of activity in Alzheimer’s disease research. Scientists are learning more about the molecular details of the disease and are optimistic that they may have drugs within the next five to 10 years to defend against its assault. But lack of public awareness of the disease’s impact means that there isn’t a push for faster research progress. “We’re grossly underspending on research for this field,” says Norman Relkin of Weill Cornell Medical College, but “we’re facing an epidemic of unprecedented magnitude.”

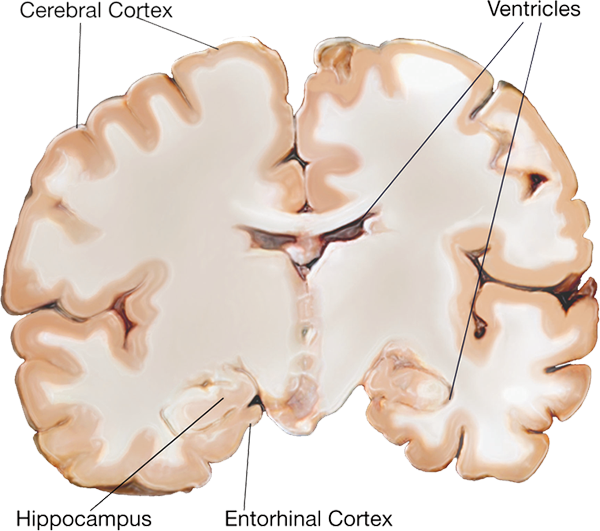

Progression of Alzheimer's disease |

|

Healthy |

|

Moderate |

|

Severe |

Alzheimer’s disease is defined by two histopathological hallmarks in the brain, amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. These were first described more than a century ago by the Bavarian psychiatrist and neuropathologist Aloysius “Alois” Alzheimer. In 1901, Alzheimer met a 51-year-old female patient, Auguste Deter, at the Frankfurt Asylum. Deter showed strange behaviors, including screaming for hours in the middle of night, and experienced hallucinations. She had been admitted into the institution because her husband, a railroad worker named Karl, could no longer take care of her. Alzheimer became obsessed with her symptoms over the next few years. When Deter died in April 1906, Alzheimer acquired her medical records and brain. He used silver staining techniques to study her brain and later that year described at a conference the plaques and tangles he saw as well as her symptoms.

Alzheimer’s disease is mostly an age-related disorder, but “there’s been a longstanding debate (about) whether Alzheimer’s disease is an obligate consequence of aging,” says Relkin. There is evidence against that notion. Rare early-onset forms of the disease, based on autosomal dominant mutations, have been characterized in individuals who, like Deter, begin to display dementia by their 50s. These early-onset forms, which bear clinical and pathological similarities to the late-onset form, underscore that Alzheimer’s is a bona fide disease and not a foregone conclusion of aging.

The plaques, found outside of neurons, are now known to be clumps largely of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid or amyloid-beta. Aβ is a product of the proteolysis of a larger transmembrane protein called amyloid precursor protein. There are more than 30 types of Aβ fragments that differ in length, but the one that is found predominantly in plaques has 42 amino acids, Aβ42.

The neurofibrillary tangles are inside of neurons. They consist of a microtubule-associated protein called tau in a hyperphosphorylated form. When tau is not hyperphosphorylated, it stabilizes microtubules, which are important for maintaining cellular structure and acting as railroad tracks for the trafficking of various organelles. Tangles are seen in other types of dementia diseases, such as Pick’s disease, but in those cases they are not accompanied by plaques.

“There is some early indication that the amyloid, whether it’s aggregates or oligomers, triggers intracellular signaling pathways that involve tau and initiate the process of tangle formation,” says Paul Fraser at the University of Toronto about Alzheimer’s disease. “But the exact mechanism hasn’t been completely figured out.”

|

| Betty Wollslager. Photo provided by Eilene Wollslager. |

Eilene Wollslager recalls the moment when the enormity of her mother’s Alzheimer’s disease hit her. A professor of communications at the University of Texas, San Antonio, Wollslager had been watching her 85-year-old mother, Betty, lose her memory little by little over the course of seven years. In 2011, Wollslager had her parents move in with her and her husband so they could take over their care. But six months ago, when she walked into the kitchen, Wollslager was stunned. “My mom is a person who drinks 20 cups of coffee a day. She is a coffee addict. She was standing in front of the coffee maker and could not figure out how to make coffee,” Wollslager recalls. “That really hit me — just how far down the road we had come.”

Betty Wollslager was an elementary school teacher who taught third- and fourth-graders for 30 years. She was among the first generation in her family to go college. She was a voracious reader and was known as the family historian. But hints of the disease began to crop up in the mid-2000s. “She had been forgetful for a number of years. She wouldn’t remember little things. She couldn’t pull up a name or a word. She would go into rooms and forget why she was there,” says Eilene Wollslager. “You thought, ‘Oh well, she’s getting older.’ But it just kept going.”

When Betty Wollslager became aware that she was becoming forgetful, she began to keep a nightly journal in which she would record the day’s events. “At first, she could do it herself. Then she would have to ask Dad for help, because she couldn’t remember what happened in the day. Then she had to ask Dad pretty much for everything. Now she doesn’t do it,” says Eilene Wollslager.

These days, Betty Wollslager recognizes her husband and daughter but doesn’t remember her daughter’s name. “She cannot tell you where she lives. She can’t tell you what year it is and what day it is,” says Eilene Wollslager. “She lives totally in the moment.”

Alzheimer’s disease takes over the brain in a specific pattern. “It’s a $64,000 question of why certain cells die and others don’t,” says Petsko. “There is no question that the disease is focal. It starts in specific regions of the brain and spreads.”

The early stages of the disease ravage the entorhinal cortex, a region near the hippocampus. From there, it spreads to other parts of the limbic system, including the hippocampus, which is involved in emotions, behavior and long-term memory. The disease then invades the neocortical areas, at which point patients may begin to show disturbances in verbal fluency, orientation and copying geometric figures.

Autopsies reveal that plaques and tangles show up at different times. Plaques seem to appear anywhere from 20 to 30 years before symptoms. Neurofibrillary tangles seem more closely timed with the onset of disease symptoms but still precede them.

The thinking now is that oligomers of Aβ and tau, precursors to the plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, trigger neuronal death. Recent evidence suggests that tau can pass from cell to cell in a prionlike fashion, causing its normal counterparts in other cells to misfold and spur cell death.

Larry Sparks of Banner Health Research says autopsies have shown that the brains of elderly people without Alzheimer’s can have plaques but no neurofibrillary tangles. The question is why, in some people, these plaques, after a certain load and time, trigger formation of neurofibrillary tangles and cause them to spread through the brain, bringing on clinical symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

The neuronal system isn’t the only one involved in the disease. Aβ and tau accumulation are thought to set off reactions involving glucose metabolism and inflammation. There are also links between insulin resistance and Alzheimer’s disease. Creighton Phelps at the National Institute on Aging explains that genetics has revealed hints of connections between the immune system and Alzheimer’s disease. “It fits that you might inherit a group of genes that make you a little more vulnerable to these protein aggregations because of your immune status,” he says.

Both Wollslager and Bottoni say it’s so hard to get their mothers to bathe that they attempt it only once a week. “It’s the weird things you battle over. My mom always was very fastidious. She always had every hair in place, crisp and clean,” says Wollslager. “We have a fight now every week about trying to get her to bathe. She thinks she’s already done it.”

Bottoni describes showering her mother as hell. “I have the heater in the bathroom to warm it up. I get everything set up in her bedroom with the blow dryer and the chair. I put her bathrobe in the dryer so she will be nice and warm. And then it’s a fight, tooth and nail.” Her mother refuses to step into the bathtub and recently has taken to screaming curses at her daughter. “Once, she punched me in the stomach. She has a good wallop,” says Bottoni with a rueful laugh. “Then another day, she got me in the jaw.”

|

| (From left) Jodi Bottoni, Jacquie Berg and their friend KC Jones. Morgan, the dog, is behind the cactus next to Bottoni. Photo provided by Bottoni. |

Researchers are certain that in Alzheimer’s disease, the processing of APP goes awry. APP, which is about 700 amino acids long and implicated in neuronal guidance and positioning during brain development, gets cleaved at least twice by two different enzymes, the ubiquitous γ-secretase and the more neuron-specific β-secretase, which is also known as BACE. The cleavage produces the series of Aβ fragments, including Aβ42 and the normally more predominant Aβ40. Scott Small of Columbia University says researchers are “legitimately embroiled in the active discussion of which of these fragments is pathogenic.”

Experts agree that Aβ42 is one culprit. The last two amino acids in Aβ42 are alanine and isoleucine, hydrophobic amino acids that confer a strong aggregation property to Aβ42 that Aβ40 doesn’t have. “If we only made Aβ40, there probably wouldn’t be such a thing as Alzheimer’s disease,” notes Dennis Selkoe of Harvard Medical School.

Researchers have focused on APP and its processing because of genetic evidence. For example, most people with Down’s syndrome develop the signs of Alzheimer’s disease if they live to be in their 50s. Those with Down’s syndrome, like early-onset Alzheimer’s patients, start accumulating plaques in their brains as teenagers or young adults and later develop neurofibrillary tangles. G. William Rebeck at Georgetown University Medical Center explains the gene for APP is on chromosome 21, the extra chromosome those with Down’s syndrome carry. With more APP than normal, those with Down’s syndrome, not all of whom develop full-blown dementia, may produce more Aβ fragments than people without the syndrome.

Then there is a mutation called A673T in APP, which is found in a small number of people in Iceland and other Scandinavian countries who never get Alzheimer’s disease. The mutation happens at a location right next to where β-secretase cuts on APP. “They not only do not get Alzheimer’s disease — they don’t even show any mild cognitive impairment,” says Petsko. “We now know from in vitro studies that mutation reduces the effectiveness of APP as a substrate for β-secretase. The end result is you make about 50 percent less Aβ than if you did not have the mutation.”

There is a smaller group of a people with a different mutation at the same site where the residue is changed to a valine instead of threonine. That change makes APP more effective as a substrate for β-secretase, and these people get early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. “That is, to me, the best smoking gun that says that the processing of APP is relevant to the development of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Petsko.

Playing into the processing of APP are mutations in the γ-secretase complex, which includes presenilins. Presenilin mutations increase the processing of APP to produce more Aβ fragments, particularly Aβ42. For example, a clan of 5,000 people in Medellín, Colombia, carries a genetic mutation in presenilins that predisposes them to early-onset Alzheimer’s disease; they begin to show cognitive impairment around age 45 and by their 50s have full-blown dementia. Recently, the medical records and samples of Deter, Alzheimer’s first patient, were recovered; she was found to have a presenilin mutation.

But Aβ42 and the other fragments are made throughout a person’s life, starting from the fetal stage. A mystery in Alzheimer’s disease is why all of a sudden these fragments turn rogue. Researchers suspect something goes awry in clearing out the Aβ42 fragments, causing them to form oligomers that go on to form plaques. One indication that this may be the case comes from a polymorphism in a gene for apolipoprotein E.

ApoEs circulate in the blood and bind to the LDL-receptor-related protein, which is involved in cholesterol sequestration and modulation of membrane lipids in the central nervous system. ApoE4 reduces the removal of Aβ fragments from the extracellular space. People who have two copies of ApoE4 are 10 times more at risk of developing Alzheimer’s than people who don’t carry the polymorphism. In the U.S., Rebeck explains, 1 percent to 2 percent of the population has two copies of the ApoE4 polymorphism. “It’s certainly not uncommon and has a strong effect on your risk of disease,” he says.

By the fall of 2012, researchers involved in three large clinical trials of potential Alzheimer’s drugs announced that the agents did not help patients. Bapineuzumab, known as bapi for short, is a monoclonal antibody that binds Aβ oligomers and is developed by Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson. The pharmaceutical company Elan generated the antibody and has a financial stake in the drug. Eli Lilly & Company is developing another antibody against Aβ called solanezumab, or sola for short, that mostly targets the monomeric form of the protein. Sola failed to stop the disease’s progress in a recent clinical trial, but there were some signs it could slow cognitive decline in patients with mild Alzheimer’s. The clinical trial failures brought on soul searching among researchers: Why did these promising drugs, which worked well in Alzheimer’s mouse models, fail in humans?

“Unfortunately, the way any field in medicine and science works, often the tests that are being carried out are tests of a hypothesis that was posed many years before,” says Relkin. He says the agents were premised on the original amyloid hypothesis. The hypothesis, put forth in the early 1990s, suggested that the amyloid plaques were the causative agents of Alzheimer’s disease. This suggested that simply removing plaques from the brain would be sufficient to halt the disease.

However, researchers now think that the plaques are simply insoluble reservoirs of the more toxic, soluble oligomers of Aβ, a thinking sometimes called the modified amyloid hypothesis. There is little evidence so far to suggest that simply removing the Aβ plaques, which the antibody-based therapies do, makes Alzheimer’s patients better.

But researchers have not lost hope in the drugs in development. “There are all kinds of indications that these should work,” says Phelps. But “these clinical trials were studying the wrong stage of the disease.”

So now sola, Roche’s gantenerumab Aβ antibody and a β-secretase inhibitor made by Lilly are being tested on patients predisposed to early-onset Alzheimer’s. Phelps explains that researchers at the National Institutes of Health in collaboration with researchers in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network are working on prevention trials by studying adults who have a parent with a mutated gene known to cause dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s disease. The NIH also is collaborating with Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, University of Antioquia in Colombia and Genentech to study an experimental Aβ antibody treatment called crenezumab on 300 Colombians who are genetically predisposed to develop early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. And, by the summer of this year, Relkin says a phase III study he has carried out with the support of the NIH and Baxter Healthcare will reveal whether an antibody preparation called IVIG harvested from the blood of healthy donors is effective in treating Alzheimer’s patients.

One of the pressing needs in the field, say researchers, is to develop therapies targeted against tau, not just Aβ. “They are both attractive targets, but the pharmaceutical industry has to do much more with tau,” says Selkoe. Because of some evidence that tau can exit a neuron and enter others, there is a moment when tau, like Aβ, is extracellular and can be attacked more easily with a therapeutic molecule. “You can hit the disorder at three or four independent points along the cascade to try and slow down the disease,” says Sparks. “Combination therapy is the future of treatment in Alzheimer’s disease.”

But Relkin, Petsko and others say researchers need to hurry. “Even in the best-case scenario, a newly developed prevention is going to take a decade or more to be approved and disseminated. By that time, we’re going to be well into the baby-boomer era, and we’re going to have a fairly unmanageable healthcare situation on our hands,” says Relkin. “We need demonstrations of drugs that work. It doesn’t matter what their mechanisms are. We shouldn’t suffer from the hubris that we know what causes the disease, but rather we need to focus on what works.”

Both Wollslager and Bottoni say there are moments of joy and pleasure in caring for their mothers. For Wollslager, it’s her mother’s wit. “The one thing that is still Mom is her sense of humor. She still teases Dad and says things that are deliberately funny,” says Wollslager. “That makes it a little more bearable.”

But not much else is left of the woman she knew. “I refer to ‘Old Mom’ and ‘New Mom,’” says Wollslager. “My mom I knew growing up isn’t there anymore. Now we have New Mom. I compartmentalize her previous self from her current self, because if I continually mourn what was lost, I can’t enjoy her in the moment.”

Bottoni is grateful that time and the disease haven’t touched her mother’s beauty. She takes great pleasure in dressing her mother in the clothes she wore as a dance instructor: pastel capris and jackets worn over colorful shirts; accessories on her long, silver-white hair; and lipstick in shades of pink. But Bottoni acknowledges the emotional and physical tolls her mother’s care has taken on her. “Unfortunately I don’t see an end to it until I put her in an Alzheimer’s unit in a nursing home,” says Bottoni.

While things are still relatively manageable, Wollslager says she holds onto the small, good moments with her mother. “There will come a day she won’t remember how to swallow. You know that’s down the road,” says Wollslager. “I just try to embrace what we have today.”

Update

Jodi Bottoni had to place her mother, Jacquie Berg, in an assisted-living home. Their friend KC Jones reports that Berg is very happy there. She has made friends, and she sings and dances. Bottoni now is trying to catch up on the rest she missed while taking care of Jacquie full time.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Scientists find bacterial ‘Achilles’ heel’ to combat antibiotic resistance

Alejandro Vila, an ASBMB Breakthroughs speaker, discussed his work on metallo-β-lactamase enzymes and their dependence on zinc.

Host vs. pathogen and the molecular arms race

Learn about the ASBMB 2025 symposium on host–pathogen interactions, to be held Sunday, April 13 at 1:50 p.m.

Richard Silverman to speak at ASBMB 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the ASBMB annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

From the Journals: JBC

How cells recover from stress. Cancer cells need cysteine to proliferate. Method to make small membrane proteins. Read about papers on these topics recently published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

ASBMB names 2025 JBC/Tabor Award winners

The six awardees are first authors of outstanding papers published in 2024 in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

Pan-kinase inhibitor for head and neck cancer enters clinical trials

A drug targeting the scaffolding function of multiple related kinases halts tumor progression.