MCP: Just drops of viper venom

pack a deadly punch

A bite from a lancehead viper can be fatal. Species in the family, among the most dangerous snakes in Central and South America, have venom that can disrupt blood clotting and cause hemorrhage, strokes and kidney failure.

Researchers at Brazil’s largest producer of anti-venoms have done a structural analysis of glycans modifying venom proteins in several species of lancehead. The report offers insight into the solubility and stability of toxic proteins from venom and into how venoms from different species vary. Scientists are working to map glycan structures back onto the proteins they modify.

Solange Serrano, a researcher at the Laboratory of Applied Toxicology at the Instituto Butantan in Sao Paulo, studies the protein toxins in lancehead venom. In a recent article in Molecular & Cellular Proteomics, scientists from Serrano’s laboratory, in collaboration with researchers at the University of New Hampshire, report on the sweet side of snake venom toxins.

The researchers looked at glycans, a group of sugar molecules attached in a complex chain, often with many branches, that can be attached to proteins. According to Serrano, most proteins in lancehead venom are modified with glycans, which can affect the proteins’ folding, stability and binding. But little is known about glycan structure in the venom.

Serrano’s graduate student Debora Andrade-Silva visited the laboratory of glycomics expert Vernon Reinhold in New Hampshire to learn techniques for structural characterization of glycans. While there, Andrade-Silva and colleagues characterized the structure of 60 glycan chains in eight lancehead, or Bothrops, species’ venoms. The researchers isolated the glycans and analyzed them by mass spectrometry, breaking down each complex molecule into smaller, simpler ions. By piecing together the spectra of many such ions, they could tell which sugars were present and how they were linked into treelike glycan structures.

Lancehead venom contains nearly 100 milligrams of protein per milliliter of liquid. At this concentration, protein solutions tend to become viscous or form gels. Analyzing the structures of glycans attached to the proteins, the researchers found that a disproportionate number were tipped with sialic acid, a sugar with a negative charge.

“Glycans containing sialic acid may help in venom solubility and increase toxin half-life,” Serrano said.

Sialic acid on a toxic enzyme may also bind to host proteins called siglecs, pulling the enzyme closer to target cells for greater effect; this has been observed in other types of venom.

While Serrano’s group researches venom composition, the applications are close to home. Another department of the Instituto Butantan produces most of the anti-venom available in Brazil. Serrano said she hopes that basic research into venom toxins will help researchers develop improved treatments for envenomation.

“The antivenoms do a reasonable job, but they are not so good at neutralizing the local effects of snakebite,” Serrano said.

These effects, including swelling, hemorrhage and necrosis, can be so severe that doctors must sometimes amputate bitten limbs. Better understanding of how venom differs between snake species could improve the efficacy of anti-venom treatment.

Andrade-Silva and Serrano are working to map the structures from the glycan inventory back onto the proteins they modify. Because some venom proteins have been repurposed as medicines, knowing more about how glycosylation helps each protein fold, hold its shape and attach to binding partners may have applications in biotechnology.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

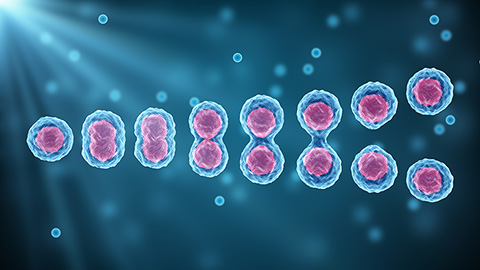

Sizing up cells: How stem cells know when to divide

Stanford University researchers find that stem cells control their size early in cell division across living multicellular systems.

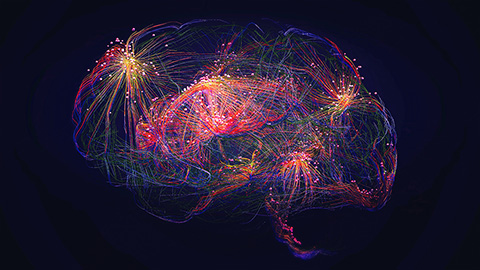

When oncogenes collide in brain development

Researchers at University Medical Center Hamburg, found that elevated oncoprotein levels within the Wnt pathway can disrupt the brain cell extracellular matrix, suggesting a new role for LIN28A in brain development.

The data that did not fit

Brent Stockwell’s perseverance and work on the small molecule erastin led to the identification of ferroptosis, a regulated form of cell death with implications for cancer, neurodegeneration and infection.

Building a career in nutrition across continents

Driven by past women in science, Kazi Sarjana Safain left Bangladesh and pursued a scientific career in the U.S.

Avoiding common figure errors in manuscript submissions

The three figure issues most often flagged during JBC’s data integrity review are background signal errors, image reuse and undeclared splicing errors. Learn how to avoid these and prevent mistakes that could impede publication.

Ragweed compound thwarts aggressive bladder and breast cancers

Scientists from the University of Michigan reveal the mechanism of action of ambrosin, a compound from ragweed, selectively attacks advanced bladder and breast cancer cells in cell-based models, highlighting its potential to treat advanced tumors.