Science in sign language

I sit across from Dan Lundberg in his office on a rainy, late-fall afternoon. He tells me about his scientific career, his eyes lit and his demeanor enthusiastic, radiating brightness against the grayness coming in through the window. But only through the interpreter can I hear his words and the energy in his voice. Lundberg, a professor of chemistry at Gallaudet University, is deaf and communicates using American Sign Language.

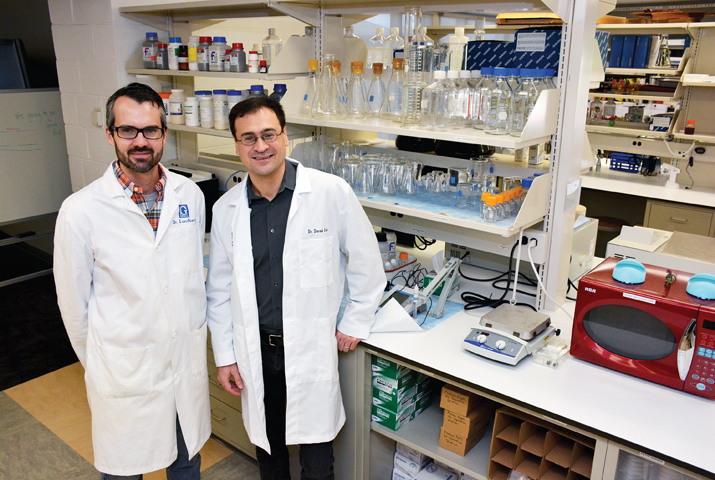

Daniel Lundberg, left, and Derek Braun Image credit Gallaudet University

Daniel Lundberg, left, and Derek Braun Image credit Gallaudet University

Lundberg’s path to professorship was not particularly unusual. As an undergraduate at Gallaudet University, the nation’s only university for the deaf and hard of hearing, he planned on continuing on to medical school. He explored different fields, though, through summer internships with the National Forest Service and labs at James Madison University and Duke University. By the end of his undergraduate studies, he had lost all interest in a career in medicine but was intrigued by pharmacology. He then met Peter Blumberg, an investigator at the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., who had post-baccalaureate fellow positions open.

Peter Blumberg

Peter Blumberg

Blumberg is a leading authority in diacylglycerol signaling and investigates the potential of downstream targets to treat cancer and pain. Blumberg’s lab was appealing to Lundberg, because it had two deaf scientists working there at the time. Blumberg is not deaf but has been providing research opportunities for deaf students and scientists for 10 years. “How successful people are, in my experience, isn’t related to whether they are deaf or not,” Blumberg tells me. “It’s related to their ability to do the sort of science we do, pay attention to detail, how hard they work – things of that sort.”

Bridging the gap

How does a principal investigator facilitate communication among deaf and hearing colleagues? Moreover, how are the large number of field-specific technical terms adopted and communicated in sign language? These communication differences are not notably challenging to work around, those I talked to say.

Blumberg taught himself American Sign Language and has interpreters stationed in the lab during the day. For lab meetings, journal clubs and research seminars, he has two interpreters present to tag-team signing. Costs for the interpreters are covered by the NIH’s Office of Research Services. The only learning curve that he experienced, Blumberg says, was realizing he needed more interpreters. Before, when he had one deaf student, he could carry out the interpreting. As more deaf fellows joined, Blumberg sought full-time interpreters for help.

Having interpreters around all day is not necessary though. “In general, interpreters are only needed during the day if we’re having lab meeting, classes, important functions or events, or presentations – poster presentations, student presentations, guest presentations from other scientists,” Lundberg says. “The rest of the day, I do not need an interpreter, because I’m in lab and it’s independent work.”

During his Ph.D. at the University of Minnesota, Lundberg used online chat platforms to speak with his adviser and colleagues. Or he wrote on a whiteboard, scratch paper, or paper towels. His adviser later suggested that he keep the scraps of paper, which “was really good advice,” Lundberg says, “because they were really good notes.”

The best way to arrange the most suitable accommodations for deaf individuals is to ask them what they need, says Derek Braun, a former postdoctoral fellow with Blumberg and currently a professor of biology at Gallaudet University. One of his ongoing projects is a collaboration with Blumberg and Lundberg to investigate the role of Ras guanyl nucleotide-releasing proteins, a downstream target of diacylglycerol, in cancer. “Not all deaf people sign,” Braun says. “Some are oral. Really, we come in every flavor imaginable. The best judge of what that person needs is usually the person.”

Signing scientific terms is not unusually challenging either. While no standardized set of signs for technical words exists, colleagues working in the same lab develop their own signs for the terms they frequently use. If each lab develops signs independently, what happens when members of different labs meet?

Larry Pearce, a technician in Blumberg’s lab who is deaf, explains to me, “It’s really not that difficult, because when an individual does not understand a sign we use, they’ll ask for clarifications and I’ll finger-spell. I’ll spell it out. They will tell me what their sign is, and I’ll tell them what our sign is. If I like their sign better, I might adopt it and use it every day, or vice-versa, and eventually it becomes more universal.”

Artificial barriers

According to the report prepared from the Workshop for Emerging Deaf and Hard of Hearing Scientists in 2012, deaf and hard of hearing college students are as likely to study science and engineering as college students of the general population.

However, less than 1 percent of science and engineering deaf and hard of hearing students continue on to Ph.D. programs compared with the 11 percent to 15 percent of students in the general population. If the daily logistics of conducting lab research are not taxing to solve, why is the attrition between undergraduate to graduate school so high?

Blumberg posits that scientists may hesitate to take in a deaf candidate because accommodating comes across as a new challenge and more work for the lab. He finds the reluctance puzzling because “in science, all the time we’re doing new things,” he says.

For Braun, the resistance seems to come from misconceptions about deaf people. “There’s a common attitude that deaf people are less educable,” Braun says. While at a meeting held by the American Society for Human Genetics in October, Braun said he stood out because he had an interpreter with him. “After one of the sessions, a geneticist came up to me,” Braun recounts, “and said he had a deaf son who wanted to become a scientist, but he, the father, didn’t realize that deaf people could become scientists.”

How the accommodations are paid for can also promote reluctance. “When an institution tries to have it come out of a departmental budget, which is smaller, the department becomes resistant to providing accommodations,” Braun says. “The best setup is when accommodations are paid for out of a central budget for the institution.”

Lundberg hesitates to call the resistance he has encountered prejudice. He says he prefers to think of it in terms of “people being exposed to new experiences.” Most people, Lundberg feels, “are very open and willing. They just need to be oriented with how things go. Like, interpreters are not needed all the time, because that is the first thing they think.”

Moving forward

After completing his Ph.D., Lundberg landed an assistant-professor position at Gallaudet and received tenure seven years later, last summer. Besides the project with Blumberg and Braun investigating RasGRP in cancer, Lundberg is expanding into environmental science and is starting a project on pharmaceutical waste in fresh water sources.

Blumberg believes that considering the deaf and hard of hearing disabled negatively skews the public perception of their abilities. “I always feel awkward when someone cites me for efforts to provide training opportunities for the disabled,” Blumberg said in his acceptance speech when he received the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology’s Ruth Kirchstein Diversity in Science Award in 2013 for his outreach activities. “The reality is that I do not consider that I have any disabled people in my group. I have a group of individuals who are defined by what they can do and who they are, not by some job-unrelated characteristic.”

Blumberg says he hopes that the productivity and success of his deaf mentees persuade other scientists to reach out. He has published 61 papers from the work of his deaf mentees. To investigators who want to encourage diversity at their institutions, Blumberg’s advice is straightforward: “None of it is tough. Go ahead and do it."

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in People

People highlights or most popular articles

Defining JNKs: Targets for drug discovery

Roger Davis will receive the Bert and Natalie Vallee Award in Biomedical Science at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.

Building better tools to decipher the lipidome

Chemical engineer–turned–biophysicist Matthew Mitsche uses curiosity, coding and creativity to tackle lipid biology, uncovering PNPLA3’s role in fatty liver disease and advancing mass spectrometry tools for studying complex lipid systems.

Summer research spotlight

The 2025 Undergraduate Research Award recipients share results and insights from their lab experiences.

Pappu wins Provost Research Excellence Award

He was recognized by Washington University for his exemplary research on intrinsically disordered proteins.

In memoriam: Rodney E. Harrington

He helped clarify how chromatin’s physical properties and DNA structure shift during interactions with proteins that control gene expression and was an ASBMB member for 43 years.

Redefining lipid biology from droplets to ferroptosis

James Olzmann will receive the ASBMB Avanti Award in Lipids at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, just outside of Washington, D.C.