The look of love

Before I leave the house, I say goodbye to my dog. Sometimes, tongue in cheek, I’ll ask her to watch the house and protect it (she’s usually half asleep in her doggie bed). Other times, I’ll tell her I won’t be long, especially if she gives me puppy-dog eyes when I start to leave.

Tobie is an 8-year-old beagle who has been in our family since she was 7 weeks old. Sometimes, she seems more like our oldest child than a pet. We often joke that she plans to throw a rager, inviting all the neighborhood dogs over, in our absence.

In the years before I had to rush out the door with my daughter for school drop-off, we had a ritual: Tobie would sit on my lap and lick my face before we parted. It left me feeling good about the day to come, especially knowing my best friend would be there when I came home, eager to see me. On some level, I believe it also eased her anxiety about being left alone in the house for hours.

Over the years, I’ve casually read, heard and witnessed the bond between canines and humans, particularly between a pet and its owner. Researchers have studied communication strategies, the evolution of personalities, and even what dogs think when interacting with their specifically bonded humans.

Domesticated dogs all originate from wolves and, through millennia, have adapted to human behavior.

While humans continue to define and study the evolution of dogs, we focus less on the convergent evolution of humans to bond with dogs. A 2015 article in the journal Science by Miho Nagasawa and colleagues began to unpack the inference that when dogs are domesticated, they adopt human “social cognitive systems involved in social attachment.”

In other words, dogs, more than any other animal (including our closer genetic relations, such as chimpanzees) have an integrated form of social communication with humans that taps into bonding strategies and has led to the human–canine relationships that many of us know and love.

The love hormone

Much of this study, and similar work, hinges on tracking and understanding the role of the so-called “love hormone,” oxytocin, or OT. As defined by Christian Gruber and colleagues in a 2010 article in Current Pharmaceutical Design, OT is an endocrine hormone comprising nine amino acids in a macrocyclic arrangement, is produced in the hypothalamus and travels along neuronal axons for release at terminals in the brain and spinal column. It is essential for smooth muscle contraction in mammary glands and the uterus, neurotransmission in the central nervous system that affects human behavior and cell-signaling functions in the ovaries and testes.

Oxytocin binds to its G-protein coupled receptor, which is mediated by proteins involved in many second messenger systems. These receptors, expressed in mammary glands and the uterus, are involved in pregnancy and nursing, but researchers, as explained in a 2018 article in BMC Psychiatry by Catherine Maud and colleagues, also have found expression in association with the central nervous system, which leads to the social and behavioral ramifications of oxytocin binding.

In humans, OT regulates a system of attachment, particularly that between a birth parent and an infant. This is often described as a loop, where the parental gaze stimulates oxytocin release in the infant, which, in turn, increases social attachment, which then loops back to the parent, and so on.

In the studies described in the 2015 Science article, scientists sought to understand the interspecies attachment between humans and dogs by relating it to the hormone OT. Some equate the possible oxytocin-mediated positive loop between dogs and humans with that between a parent and infant. Our dogs are like our children — or at least our biochemistry thinks so.

The studies

To test this hypothesis, the researchers performed two studies, which they elaborated on in later work. First, they examined urinary oxytocin concentrations in dogs and owners during mutual gazing and other interactions for up to 30 minutes. They then compared this with the same interactions with hand-raised wolves to determine if the oxytocin loop was a product of dog–human coevolution. Second, they administered oxytocin to dogs directly through an aerosol spray to study their subsequent gazing behaviors as well as the urinary oxytocin concentrations excreted by the owners as a result.

Interactions in these studies included dog-to-human gazing, humans talking to dogs and humans touching dogs. The greatest changes in oxytocin production, as well as the highest collected urinary concentrations, were for the gazing groups.

When the researchers compared the dog experiments with those done with domesticated wolves, the wolf-to-owner gaze did not correlate with any appreciable change in oxytocin levels. This provided more evidence that dog-to-owner gazing is a form of communication that co-evolved as dogs were domesticated from wolves, and this is manifested by the positive response, as seen by the oxytocin release, in both the owner and dog.

Further studies examined sex differences in dogs; a dose of oxytocin significantly increased dog-to-owner gazing to female dogs but much less in male dogs. Urinary collections of oxytocin showed higher increases in concentration in owners of female dogs treated with the peptide hormone, as well. This pointed to heightened gazing between female dogs and owners and consequent stimulation of oxytocin release in the owners. Providing humans with administered oxytocin also shows sex-based differences, attesting to the possibility that females are more sensitive to oxytocin’s effects or that the alternative, vasopressin receptor, is activated in males. No sex differences were noted in measures of natural oxytocin production measured, only when the hormone was administered.

The bonding loop

For a human baby, mutual gazing with a parent is a healthy part of bonding. In fact, according to Jun Shinozaki and colleagues’ 2007 article in the journal Neuroreport, when humans are shown pictures of family members, magnetic resonance imaging shows activated areas of the brain (specifically the anterior cingulate cortex) that are receptive to oxytocin. These same areas are ignited when humans are presented with pictures of their dogs. So, humans may feel affection in similar ways for their dogs and their human family members.

When dogs were domesticated, it seems their neural systems that use gaze as part of communication evolved to activate the human oxytocin release associated with bonding among family members, especially between a parent and child. The proposed interspecies oxytocin-mediated positive loop related to dog-human bonding reinforces the relationship between dogs and humans.

After my husband and I discussed these findings, he decided to “stare down” Tobie in an effort to initiate chemical reactions and behavioral feelings. Tobie seemed surprised and didn’t maintain the gaze for very long, but biochemically I knew they both were probably surging with the love hormone.

In more organic instances, loving gazes between humans and their pets are certainly cherished. When Tobie sits in my lap on a bad day, licks tears when I’m sad or jumps up on me when I’m celebrating, I think she truly understands me. Dogs truly have keyed into our emotions and evolved realistic communication methods that feed back from us to them in a harmonious loop. Since Tobie first imprinted into our lives and hearts, I’ve never doubted that she was my first baby.

Gaze lovingly into your dog’s eyes today, and see if it doesn’t make you feel a bit more content.

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

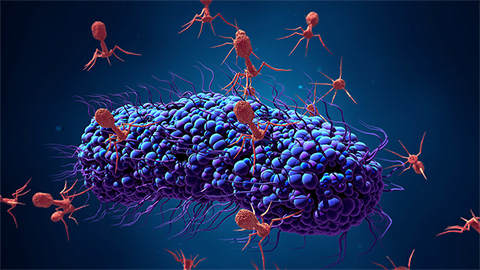

Bacteriophage protein could make queso fresco safer

Researchers characterized the structure and function of PlyP100, a bacteriophage protein that shows promise as a food-safe antimicrobial for preventing Listeria monocytogenes growth in fresh cheeses.

Building the blueprint to block HIV

Wesley Sundquist will present his work on the HIV capsid and revolutionary drug, Lenacapavir, at the ASBMB Annual Meeting, March 7–10, in Maryland.

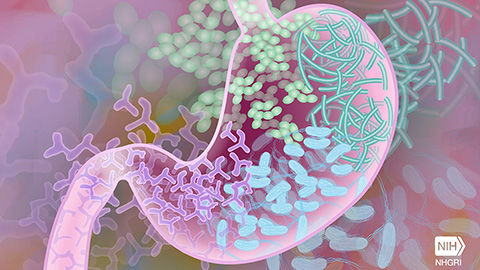

Gut microbes hijack cancer pathway in high-fat diets

Researchers at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research found that a high-fat diet increases ammonia-producing bacteria in the gut microbiome of mice, which in turn disrupts TGF-β signaling and promotes colorectal cancer.

Mapping fentanyl’s cellular footprint

Using a new imaging method, researchers at State University of New York at Buffalo traced fentanyl’s effects inside brain immune cells, revealing how the drug alters lipid droplets, pointing to new paths for addiction diagnostics.

Designing life’s building blocks with AI

Tanja Kortemme, a professor at the University of California, San Francisco, will discuss her research using computational biology to engineer proteins at the 2026 ASBMB Annual Meeting.

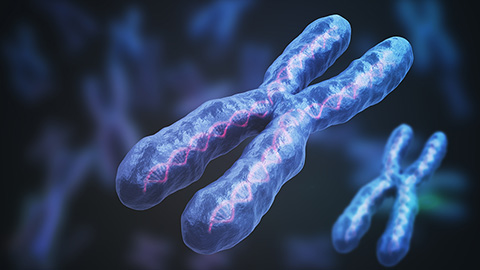

Cholesterol as a novel biomarker for Fragile X syndrome

Researchers in Quebec identified lower levels of a brain cholesterol metabolite, 24-hydroxycholesterol, in patients with fragile X syndrome, a finding that could provide a simple blood-based biomarker for understanding and managing the condition.